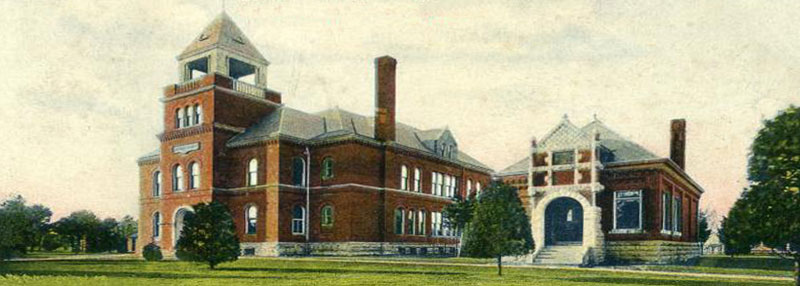

Old Nemaha County Courthouse in Seneca, Kansas.

Towns & Places:

Baileyville

Bern

Centralia

Corning

Goff

Oneida

Sabetha

Seneca

Wetmore

Museums & Historic Sites

Mormon Disaster at Murphy Lake

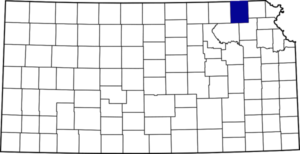

Nemaha County, Kansas, was one of the original 33 counties created by the first territorial legislature in 1855.

The county took its name from the Nemaha River, which in the Indians’ language meant “no papoose” or “muddy water,” indicating the malarious character of the climate at that time.

The early history of the county is rich in trail history. Many immigrants to Oregon passed through the county in the 1840s and 1850s as they journeyed from St. Joseph, Missouri, to connect with the Oregon Trail at Marysville, Kansas. The Fort Leavenworth-Fort Kearny Military Road took soldiers and supplies through the county as they traveled to Fort Kearney, Nebraska. The Overland Stage Route of the 1850s became the Pony Express route in the 1860s. Lane’s Trail brought northerners into Kansas from the east into Nemaha County. A branch of the California Trail also passed through the area.

Some historians claim that Francisco Vazquez de Coronado visited Nemaha County and that he reached its northern boundary in August 1851. However, this has not been verified.

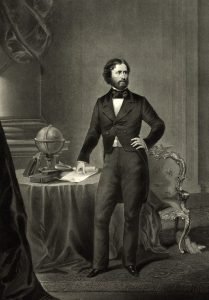

The first important expedition known to have traveled across the area was John C. Fremont’s second journey in 1842. He entered the county south of Sabetha, extending northwest to Baker’s Ford, turning south to near Seneca, and then northwest again, crossing the county line near the former village of Clear Creek. The path was difficult because the expedition struggled to cross streams and had to learn their locations. With slight modifications, the Mormons later traveled this road in 1844, at the beginning of their exodus to Utah. In 1849, it was the trail of the California gold-seekers and, subsequently, the military road, along which passed many of the troops bound for the Far West.

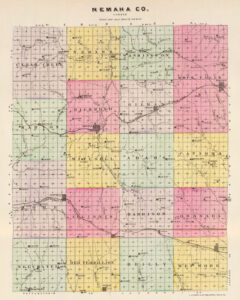

Nemaha County is bisected by its namesake, the Nemaha River, which flows north into Nebraska. Its tributaries are Deer, Harris, Illinois, Grasshopper, Pony, Rock, Vermillion, French, and Turkey Creeks.

The area is formed by glacial deposits, primarily composed of gently rolling hills. Besides the Nemaha River, these hills are the headwaters of the Delaware River on the county’s east side and the Vermillion River on the south side.

The county’s first settlers were mainly northerners from New York, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa. A second “wave” of immigration brought families from Germany and Switzerland to help settle the county.

The earliest settlement was made in 1854, when W. W. Moore was located near Baker’s Ford, nine miles north of where Seneca now stands. The same year, Walter D. Beeles, Greenberry Key, Thomas, John C., and Jacob B. Newton settled in the same vicinity. John O’Laughlin took a claim on Turkey Creek and B.F. Hicks in Capioma Township. The settlers in 1855 were James McCallister, William Barnes, Samuel Magill, and Robert Rea in Capioma Township; David Locknane, in Granada Township; James Thompson, John S. Doyle, Cyrus Dolman, Elias B. Newton, H.H. Lanham, and his wife, S. M. Lanham, and Joseph Lanham, in Richmond township; William M. Berry and L.J. McGown, in Valley Township; Horace M. Newton, in Richmond Township; William Harris, on the creek that bears his name; Hiram Burger, George Frederick, and George Goppelt, on Turkey Creek. An African American named Moses Fatley claimed that he sold the following year to Edward McCaffery for $200. He bought his freedom, the freedom of his wife, his sister, and two of her children. C. Minger and his wife settled in Washington Township, and Reuben Wolfley in Wetmore Township.

These early claims were taken without a warrant, as there were no facilities for entry and no place at which payment could be made to the government. The earliest payments were made in 1857.

When Nemaha County was organized in 1855, the legislature established the county seat at Richmond. For several years, the official business center was located in the combined store and hotel building of A. G. Woodward.

The Christian denomination in Granada Township built the first church in 1856. The first schools were built in Granada Township in 1856 and America City in Red Vermillion Township in 1857. The first post offices were in Central City in 1856 and America City in 1858.

The county was officially organized on April 4, 1858, by W.W. Moore, Walter Beeles, Greenbury Key, Thomas, John, and Jacob Newton, John O’Laughlin, and B.F. Hicks. The third county west of the Missouri River in the northern tier was one of the 19 counties to be organized that year. It is bounded on the north by the State of Nebraska, on the east by Brown County, on the south by Jackson and Pottawatomie Counties, and on the west by Marshall County.

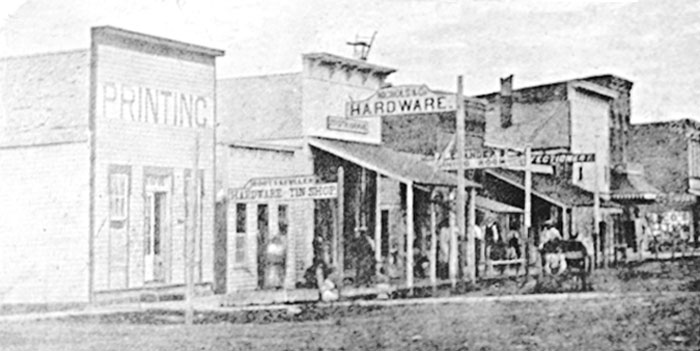

In June 1858, an election was held to choose a location for the permanent county seat. By this time, Seneca had been established and had won after three elections on the question. The other contenders were Wheatland and Richmond. The county seat moved to Seneca following an 1858 election. Unfortunately, the first Seneca courthouse burned, and the second proved too small. The first election for county officers was held in 1859.

Very little of the violence that was occurring at that time in Kansas over the question of slavery occurred in Nemaha County, although both pro-slavery and Free State men had settled here to help their side win. The only slaveholder in the county was L.R. Wheeler of Rock Creek Township, who held two slaves until 1859.

Some historians state that John Brown spent his last night in Kansas at Albany. The underground railway came through the eastern part of the county, and one of the stations was at Lexington, three miles south of the present town of Sabetha. In 1859, Brown, while escorting 14 former slaves to freedom over the famous “Lane Road,” was held up on Straight Creek in Jackson County for three days by those who hoped to obtain the rewards offered to him. He was relieved by Colonel John Ritchie of Topeka, who escorted him to Albany, where he spent the night, proceeding to Nebraska the next day.

The year 1860 was a tough one for the settlers. The county had grown from 99 in 1855 to over 2,000 without experiencing severe setbacks. However, the drought, storms, and other weather conditions led to this period being called “the famine of 1860.” The main articles on diet were cornbread and sorghum molasses, and the settlers who could get enough of them were lucky. F.P. Baker of Centralia was on the territorial relief committee and remained at Atchison during the winter of 1860-61, attending to the committee’s office. Through him, many residents were relieved of suffering.

In 1860, Nemaha County’s population was 2,436.

Preemptions were made up to 1860 at the land office at Kickapoo, where entries were made for the district of which Nemaha County was a part. The county’s settlement and development began when the pro-slavery element held the upper hand in Kansas, and most of the early towns failed after Kansas declared itself a Free State. Among those that disappeared were Central City, the county’s first post office; Pacific City; Lincoln, Ash Point; Urbana, the county’s first town; Wheatland; and Richmond, the county’s first county seat.

That year, Edwin Avery, an early-day farmer who took a claim in Nemaha County, described his first glimpse of the old California Trail that passed through Nemaha County in 1860.

“I first saw it in the Elwood bottoms across the river from St. Joseph, Missouri, on December 1, 56 years ago. The trail was located in the 1840s. It forked just west of Troy in Doniphan County. One fork went by Highland, the other across Wolf River directly through Hiawatha, Old Fairview, past Spring Grove, the farms of Ed Brown and France Dunlap, and directly past the Grand Island depot in Sabetha to the Coleman farm. From there, it continued to the Baker Crossing on the Nemaha, now called Taylor’s Rapids. It passed through Baileyville in the county’s west end and on to Marysville, Fairbury, and then to Fort Laramie, Wyoming, and California.”

In the vicinity of Sabetha were many graves of travelers over the Santa Fe and California Trails, who, unable to survive the hardships of the trip, died and were buried with scant ceremony. Mrs. Ruth Willis, who came to Nemaha County over the trail, starting from Elwood on the bank of the Missouri River opposite St. Joseph, recalled that the travel was all in the warm months. In the woods surrounding Sabetha were many wild plum trees. When the body of a forty-niner was buried, the rest of the train would sit around for a while and eat plums. As a result, a small plum grove grew around the early-day graves.

Edwin Avery said that within a distance of 16 miles from Sabetha, he had counted 13 such graves. All of them were directly on the old trail, which later became a highway. A few graves were also scattered on adjacent farms. A famous one on Matthias Strahm’s farm is called the McCloud grave. McCloud, it is recalled, was returning from California. He was followed by an enemy who overtook him at this point, killing him. It was afterward learned that McCloud was not the man whom the murderer was looking for.

When the Civil War broke out, the government commissioned A. W. Williams of Sabetha as captain and, by August 1861, had successfully raised 150 men from Nemaha, Marshall, and Brown Counties. As the volunteers were enlisted, they went to temporary barracks at Sabetha, where they remained for a month at Williams’s expense. In September, they proceeded to Leavenworth, where 100 were made members of Company D of the Eighth Kansas, and 50 were mustered into other companies. Nemaha County contributed about one-third of these men. A little later, George Graham, a member of the legislature from Nemaha County in 1859, enlisted a squad of 30 men who went to Leavenworth and connected themselves with various regiments. Altogether, 218 Nemaha County men enlisted, including every able-bodied man in the settlements; Sabetha had but one man left.

Prior to the state election of 1866, there were stirring times over black and women’s suffrage, and some of the leaders in both causes held meetings in the county, notably Lucy Stone and her husband, Henry B. Blackwell, Reverend Olympia Brown, and Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The county’s vote on the black suffrage amendment was 251 to 421 against it, and the women’s suffrage amendment was defeated by 427 to 227.

There was one lynching and one legal execution in the county. The lynching took place at Baker’s Ford in 1865. The victim was Miles N. Carter, a horse thief who shot and killed John H. Blevins. Carter was taken from the jail at Seneca at 11 p.m. by 20 men who overpowered the guard. The following day, his body was found hanging from a tree at Baker’s Ford. The legal execution was held near the jail on September 18, 1868, with Melvin Baughn being the victim. He had shot and killed Jesse S. Dennis in 1866 and had managed to escape punishment for two years, though he was arrested several times.

In the meantime, the Atchison & Pike’s Peak Railroad, later called the Missouri Pacific, was the first railroad to enter the county in 1866. The stations along the route were Wetmore, Sother, Corning, and Centralia. The St. Joseph & Denver City Railroad entered the county in 1870, entering at Sabetha and passing near Onedia, Seneca, and Baileyville. Later, that line became the St. Joseph & Grand Island. The Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific entered near the central part of the north line and extended across the northeast corner through Bern, Berwick, and Sabetha. A second line of the Missouri Pacific entered from the west, 11 miles south of the Nebraska line, and extended southeast through Baileyville, Seneca, Kelly, Goff, and Bancroft.

A third courthouse was built on the current site in 1871; however, it burned down.

Due to the grasshopper invasion of 1874, about 1,000 people needed clothing, and 250 needed rations in the winter of 1874-75.

A fourth courthouse was built on the same site in 1877.

In 1875, the county’s population was 7,104.

In 1876, farming employed 81% of the settlers, while mines and manufacturers accounted for about 8%.

At that time, 10% of the area was bottomland, and t3%was forest.

Two railroads served the county: the St. Joseph and Denver City, with their principal stations at Seneca and the Central Branch of the Union Pacific Railroad at Wetmore, Corning, and Centralia.

There are 77 districts and 7-1 schoolhouses valued at $70,553, plus a Catholic parochial school in Seneca. The county had nine church buildings valued at $34,900.

On May 30, 1879, the “Irving, Kansas Tornado” passed through Nemaha County. This F4 tornado damaged a path 800 yards wide and 100 miles long. Eighteen people were killed, and 60 were injured.

In 1896, another tornado damaged several buildings, including the courthouse. However, the building was repaired.

In 1900, Nemaha County’s population peaked at 20,376.

By 1910, the county had a population of 19,072. Its economy was based on farming, and product income amounted to $5,307,178. Corn was the leading field crop, followed by oats, Irish potatoes, and wheat. The assessed value of all property in the county was $40,652,775.

Nemaha County remained a rich agricultural area in the following decades. However, as the farms expanded and technology improved, the county’s population declined.

In 1937, the beautiful courthouse built in 1877 had deteriorated, and for the next 18 years, the county offices were located in various places around town.

A new modernist Nemaha County Courthouse was built from 1954 to 1955. It continues to serve the county today.

As of the 2020 census, the county population was 10,273.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated March 2026

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Kansas State Historical Society

Nemaha County Gen Web

Nemaha County Historical Society

Society of Architectural Historians

Tuttle, Charles. A New Centennial History of Kansas, 1876.

Wikipedia