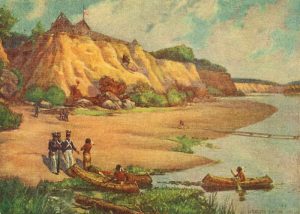

Water transport in Kansas began with Native American canoes, and later when fur traders and trappers took to the streams on keelboats and flat-bottomed boats along the Arkansas, Cottonwood, Kansas, Missouri, and Neosho Rivers, their various tributaries, or in any place where was practical.

When the first white settlers came to Kansas, there were no railroads west of the Mississippi River, and the various watercourses were depended upon to furnish the means of transportation.

However, watercraft opportunities on the semi-arid Plains were limited due to modest rainfalls and low stream levels during much of the year. The Missouri River and portions of the Arkansas and Kansas Rivers were useful, but only to the areas along their immediate navigable channels. However, steamboats helped the process of white settlement, especially in some isolated places.

As early as 1819, four steamboats — the Thomas Jefferson, Expedition, R.M. Johnson, and Western Engineer — were built to navigate the upper Missouri River and were used in the first Yellowstone expedition. In 1830, a steamboat called the Car of Commerce was built for the Missouri River trade but sank near the river’s mouth two years later.

The Yellowstone ascended the river in 1831, and between that time and 1840, the Assiniboine and the Astoria made regular trips. When Kansas was organized as a territory, the best-known steamers on the Missouri River were the A.C. Goddin, the A.B. Chambers, and the Kate Swinney. The last-named, a side-wheeler 200 feet long and 30 feet wide, sank on the upper river on August 1, 1855.

When the Excel, a vessel of 79 tons with a draft of only two feet, made its way up the Kansas River in April 1854 with goods for Fort Riley, it was an important day in Kansas transport. This first attempt to navigate the river by steam was made by Captain C.K. Baker, who returned to Kansas City in 24 hours, stopping at 30 landings.

In 1855, eight new steamboats attempted to navigate the Kansas River, including the Bee, New Lucy, Hartford, Lizzie, Emma Harmon, Financier No. 2, Saranak, and Perry. The Hartford made but one trip. On June 3, she ran aground a short distance above the mouth of the Big Blue River, where she lay for a month waiting for high water. With a rise in the river, she dropped down to Manhattan, where she unloaded her cargo, and with the subsequent rise, started for Kansas City but grounded opposite St. Mary’s Mission, where she caught fire and burned. The bell of this boat was later installed in the steeple of the Methodist Church in Manhattan.

In 1856, the steamers Perry, Lewis Burns, Far West, and Brazil appeared on the Kansas River. This year, the flatboat Pioneer took out the first freight load from up the river, arriving at Kansas City in April. The following year, four new steamboats were added. They were the Lightfoot, Violet, Lacon, and Otis Webb. The Lightfoot of Quindaro, a stern-wheeler, was the first steamboat ever built in Kansas. The Violet was built at Pittsburg. She arrived at Kansas City on April 7, 1857, and two days later reached Lawrence. Here, the captain noticed the river falling and declined to go further. Discharging his cargo and passengers, he started back down the river and arrived at Kansas City on May 10, having spent most of a month on the sand bars. The vessel never tried a second trip.

In 1858, the Otis Webb, the Minnie Belle, and the Kansas River, but in 1859 came the Silver Lake, Morning Star, Gus Linn, Adelia, Colona, Star of the West, and the Kansas Valley. In 1860, the Eureka, Izetta, and Mansfield were added to the list. Then came the Civil War, but little was done in river commerce until peace was restored to the country. The Tom Morgan and Emma began the navigation of the Kansas River in 1864; the Hiram Wood, Jacob Sass, and E. Hensley were put in commission in 1865, and in 1866, the Alexander Majors was added.

Many difficulties attended the early navigation of the Kansas River. Wood was used for fuel, and it was not unusual for a boat to tie up while the crew went ashore to cut trees and lay in a supply of wood. Low steam levels and delays were common even when conditions were ideal. The vessels could not travel in the winter when the ice broke or jammed and caused flooding. Boiler explosions, fires, and confrontations with fallen trees and snags were reoccurring events that caused headaches to shippers and travelers alike.

On one occasion, the Financier No. 2 ascended the Republican River for 40 miles by way of experiment. This was the farthest that river had ever been navigated.

“The bed of the Kansas River, like that of the Missouri, is quicksand, ever-changing, and ever-dangerous while the water will not average over two feet in depth at any place for a distance of 500 feet along its banks. If the bottom was rock and the banks precipitous, a line of steamers would pay well, but as it is, no sensible capitalist will invest his money in a single boat. Kansas is destined by nature to be the Railroad state.”

— St. Louis Democrat, November 18, 1855

When the counties of Cowley, Sedgwick, and Sumner were settled about 1870, the question of steamboat navigation on the Arkansas River became one of interest to the settlers, who were desirous of finding an outlet to market. In the fall of 1875, A.W. Berkey and A.C. Winton of Cowley County built a flatboat at Arkansas City and loaded it with flour, which they took down the river and sold at Little Rock, Arkansas. Upon their return, a stock company was formed to purchase a steamboat. A light draft boat was bought, and it ascended the river nearly to Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, when the engines were found to be of insufficient power to stem the current. In the summer of 1878, W.H. Speer and Amos Walton built a flatboat 50 feet long and 16 feet wide, equipped it with a ten horse-power thresher engine, and with this novel craft, made several trips up and down the river for a distance of 60 miles from Arkansas City while the water was at a low stage.

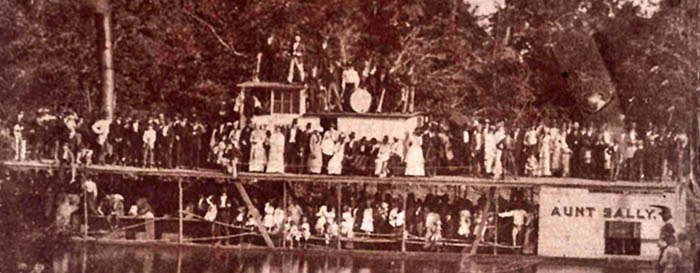

Through correspondence, the businessmen of Little Rock were induced to send a boat on a trial trip to Kansas. The boat selected was the Aunt Sally, which had been built for the bayou cotton trade of Arkansas. She arrived at Arkansas City on June 30, 1878, and the boat’s officers expressed the opinion that a boat built especially for the purpose could make regular trips up and down the river at all seasons of the year. Thus encouraged, McCloskey Seymore had the Cherokee built at Arkansas City. This boat was launched on November 6, 1878; it was 85 feet long, 22 feet wide, and had a draught when loaded to the guards of only 16 inches. Other steamers were soon built for the Arkansas River trade. Still, before the commerce of the Arkansas River was fully established, the railroad came, making the operation of the steamboats unprofitable.

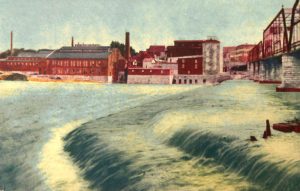

Even after the coming of the railroad, the presence of river commerce on the Missouri River remained significant for several Kansas communities, including Atchison and Leavenworth. Even into the 21st century, some towboats continued to haul barges on the Missouri River.

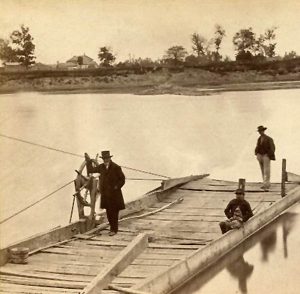

Another important mode of water transportation was the once-popular ferry boats. These usually primitive affairs allowed travelers on foot, horseback, or wagons to cross rivers and streams that could not be forded safely. Generally inexpensive to build, they were operated using oars, draft animals, or steam power. In time, they also became obsolete as bridges were built.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated September 2023.

Also See:

History Along the Arkansas River

Kansas River – Explorations Beyond Missouri

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Kansas State Historical Society