The few Free-Staters who settled in Atchison, Kansas previous to 1857 were, with two or three exceptions, very careful not to express their sentiments. Up to the spring of that year, there was no political organization in the county opposed to the principle of slavery. Occasionally; however, very early in the conflict, someone like the Reverend Pardee Butler of the Christian Church, reckless of bodily consequences, ventured to uphold his Abolitionist opinions, even upon the corner of the streets.

In the month of August 1855, a black woman “belonging” to Grafton Thomassen, the sawmill man, was found drowned in the river. A gentleman from Cincinnati, Ohio — J. W. B. Kelley, a lawyer by profession and a Free-soiler in politics, made the mistake of expressing his opinion that if she had been treated better she would not have committed suicide.

He went on to throw out more remarks on the subject of slavery, which were offensive to the pro-slavery party. Thomassen was sufficiently angered enough that he physically beat Kelley up and was sustained in his conduct by a large meeting of Atchison’s townsmen. The townsmen quickly made several resolutions concerning Kelley:

-

Resolved, That one J. W. B. Kelley, hailing from Cincinnati, having upon sundry occasions denounced our institutions and declared all Pro-slavery men ruffians, we deem it an act of kindness to rid him of such company, and therefore command him to leave the town of Atchison one hour after having been informed of the passage of this resolution, never more to show himself in this vicinity.

Resolved, That one J. W. B. Kelley, hailing from Cincinnati, having upon sundry occasions denounced our institutions and declared all Pro-slavery men ruffians, we deem it an act of kindness to rid him of such company, and therefore command him to leave the town of Atchison one hour after having been informed of the passage of this resolution, never more to show himself in this vicinity. - Resolved 2d. That in case he fails to obey this reasonable command, we inflict upon him such punishment as the nature of the case and circumstances may require.

- Resolved, 3d. That other emissaries of this Abolitionist Society, now in our midst tampering with our slaves, are warned to leave, else they will meet the reward which their nefarious designs so justly merit – hemp.

- Resolved, 4d. That we approve and applaud our fellow townsman, Grafton Thomassen, for the castigation administered to said J. W. B. Kelley, whose presence among us is a libel upon our good standing and a disgrace to our community.

- Resolved, 5th. That we recommend the good work of purging our town of all resident Abolitionists; and after cleansing our town of such nuisances, shall do the same for the settlers on Walnut and Independence creeks, whose propensities for cattle stealing are well known to many.

- Resolved, 6th. That the chairman appoint a committee of three to wait upon said Kelley and acquaint him with the action of this meeting.

- Resolved, 7th. That the proceedings of this meeting be published, that the world may know our determination.

It was further agreed that copies of these resolutions be made out and circulated for the signatures of all the townsmen, and all who refused to sign them should be considered and treated as abolitionists.

Reverend Pardee Butler lived upon his claim, 12 miles west of Atchison. On August 16th, very soon after this large and enthusiastic meeting had been held, he came to town on his way to the East, bound on business. But some of his pro-slavery enemies said “he arrived in town, with a view of starting for the East, probably for the purpose of getting a fresh supply of Free-soilers from the penitentiaries and pest-holes of the Northern States.”

Being obliged to wait for a boat until morning, Pardee stayed at the National Hotel and then proceeded to make the rounds of the town, expressing himself freely on Free State and Abolitionist doctrines, and being particularly severe upon the actions of the meeting which passed the Thomassen-Kelley resolutions. He declared that there were many people in Atchison who were Free-soilers at heart, but feared to avow their sentiments. He, however, would express his views wherever he was. Reverend Butler, in fact, preached the “foulest Abolitionist heresies,” and was considered a dangerous man, to be let alone.

In the course of a conversation which he had at the post office with Robert S. Kelley, publisher of the local newspaper, Butler informed him that he would have become a regular subscriber of his paper, had he not disliked the spirit of violence which characterized it.

To this, Kelley replied, “I look upon all Free-soilers as rogues, and they ought to be treated as such.”

Butler responded, “I am a Free-soiler and expect to vote for Kansas to be a Free State.”

“I do not expect you will be allowed to vote,” was the reply.

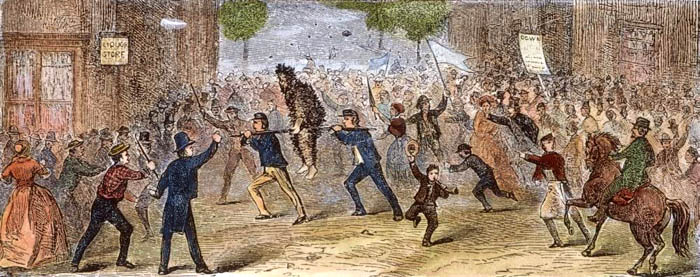

The next morning Kelley called at the hotel with the resolutions which had been adopted by the public meeting, and the signature to which was to be made the test of political faith. Of course, Butler refused to sign the pro-slavery document and walked down the stairs into the street. A crowd was there awaiting him, which increased as they dragged the abolitionist victim along towards the river, saying they were going to drown him. A vote was taken upon the mode of punishment which ought to be accorded to him, and a decided verdict of death by hanging was rendered. Ironically, Kelley ended up saving Butler’s life, by talking the other townsmen into sending him down the Missouri River on a raft instead.

The particulars of his treatment were later given by the Reverend Butler himself:

“When we arrived at the bank, Kelley painted my face with black paint, marking upon it the letter ‘R’. The company had increased to some thirty or forty persons. Without any trial, witness, judge, counsel, or jury, for about two hours I was a sort of target at which were hurled imprecations, curses, arguments, entreaties, accusations and interrogations. They constructed a raft of three cottonwood saw logs, fastened together with inch plank nailed to the logs, upon which they put me and sent me down the Missouri River. The raft was towed out to the middle of the stream with a canoe. Robert S. Kelley held the rope that towed the raft.

They gave me neither rudder, oar, nor anything else to manage my raft with. They put up a flag on the raft with the following inscriptions on it: ‘Eastern Emigrant Aid Express,’ ‘The Reverend Pardee Butler again for the underground railroad,’ and ‘The way they are served in Kansas,’ ‘For Boston,’ ‘Cargo insured, unavoidable danger of the Missourians and Missouri River excepted,’ ‘Let future emissaries from the North beware,’ ‘Our hemp crop is sufficient to reward all such scoundrels.’ They threatened to shoot me if I pulled the flag down. I pulled it down, cut the flag off the flag-staff, made a paddle of the flag-staff, and ultimately got ashore about six miles below.”

On April 30, 1856, after Reverend Pardee Butler had survived his voyage on the raft, he again ventured to make his appearance in the pro-slavery town of Atchison, where, as he would later record:

“I spoke to no one in town, save two merchants of the place with whom I had business transactions since my first arrival in the Territory. Having remained only a few minutes, I went to my buggy to resume my journey, when I was assaulted by Robert S. Kelley, junior editor of the Squatter Sovereign, and others; was dragged into a grocery, and there, surrounded by a company of South Carolinians, who are reported to have been sent out by a Southern Emigrant Aid Society. After exposing me to every sort of indignity they stripped me to the waist, covered my body with tar, and then for want of feathers applied cotton-wool. Having appointed a committee of three to certainly hang me the next time I should come to Atchison, they tossed my clothes into the buggy, put me therein, accompanied me to the suburbs of the town, and sent me naked upon the prairie. I adjusted my attire about me as best I could, and hastened to rejoin my wife and two little ones on the banks of Stranger Creek. It was rather a sorrowful meeting after so long a parting.”

The Wakarusa War, the Free-State elections, the obvious determination of the Free-State Party to convene their legislature in March, and the consequent bold attitude assumed by the people of Lawrence, kept alive the pro-slavery town of Atchison and sparked the fires of political feelings. In March 1856, numerous men from South Carolina arrived by steamer, were subsequently formed into a company, and commanded by Captain F. G. Palmer and First Lieutenant Robert De Treville. A home company had already been formed commanded by Captain John H. Stringfellow and First Lieutenant Robert S. Kelley. Arms were shipped from Fort Leavenworth and by the end of April, the companies were waiting to be led to an assault upon Lawrence.

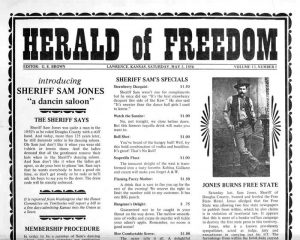

In accordance with Judge Samuel Lecompte’s charge of May 5th, the grand jury of Douglas County recommended the abatement of The Herald of Freedom and the “Free-State Hotel,” at Lawrence, as public nuisances — this newspaper having stirred up a rebellion against the territorial authorities, and the hotel having been armed and equipped as a regular fortress of war.

In the meantime, public meetings were held in Lawrence and communications were addressed to the United States Marshal, declaring Lawrence to be order-loving and law-abiding, and that her enemies were bent upon her destruction, pretending that they wished only to preserve the peace.

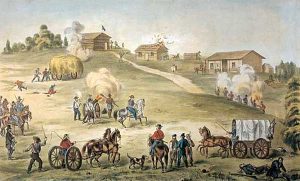

The preparations for the attack continued and on May 21st the besiegers formed quite an army. The South Carolina Company of Atchison was among the first to commence the assault upon Lawrence and before the city was fairly subjugated “its flag was planted upon the rifle pit of the enemy.”

So says the Sovereign, whose editors were two of the commanders of the attack. The newspaper continues: “It was then carried by its brave bearer and stationed upon the Herald of Freedom printing office, and from there to the large hotel and fortress of the Yankees, where it proudly waved until the artillery commenced battering down the building. Our company was composed mostly of South Carolinians, under command of Captain Robert De Terville, late of Charleston, South Carolina, and we venture the prediction that a braver set of men than are found in its ranks never bore arms.” The brave troops from Atchison returned proudly to their home, the commander of all the infantry having been one of their fellow townsmen, Colonel John H. Stringfellow, of the Squatter Sovereign. Stringfellow, without dispute, was the most bitter pro-slavery man in the territory, and kept up an everlasting din about avenging “the shooting down of our men without provocation wherever they met them.” Its watchword was “Death to all Yankees and traitors in Kansas!” The attack is since known as the Sacking of Lawrence. At a mass meeting held in June 1856, its editor, Robert S. Kelley David Atchison, Colonel Abell, Captain De Treville, others made speeches.

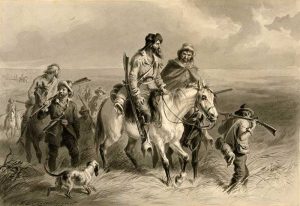

During the summer, the John Brown war and general excitement caused the citizens of Atchison to form another company — the “Atchison Guards,” commanded by John Robertson, who was prominent in the Battle of Hickory Point. By the first days of September 1856, General James H. Lane and Colonel Harvey were well on their way towards Lecompton, to rescue the Free-State prisoners who were confined there. Because of General Lane’s delay in making his appearance, Colonel Harvey thought the movement against the territorial capital had been abandoned and therefore turned his attention to Captain F. G. Palmer, the Pro-slavery commander of Atchison, who had given the Free-soilers much trouble at Slough Creek, 15 miles from Lecompton. The forces were returning from Lecompton to Atchison and had camped for the night. Captain Palmer’s South Carolina troops undoubtedly were thoroughly wearied, for they were sound asleep and had no pickets out when Colonel Harvey arrived and surrounded the camp. Every one of the 22 soldiers was taken prisoner, but Captain Palmer and Lieutenant Morrall, who were sleeping a little apart from the rest, escaped. In the slight scrimmage, two of the men were wounded. All were taken before they were fairly awake, and surrendered their guns, sidearms, 12 horses, four oxen, two wagons, carpet bags, etc. At daylight, they were released and arrived at Atchison the same day, rather low spirited. But this was not the end of the triumph of Colonel Harvey over the chivalry of Atchison.

On September 12th, Governor John Geary, the newly-appointed Chief Executive of the Territory, issued his proclamation ordering all captains of militia to disband their forces, seeing that such commands were being used as political and party agents, and claiming that he had sufficient United States troops for any probable emergency. General Lane’s forces at once disbanded, but Colonel Harvey, thinking that he was justified in punishing Captain H.A. Lowe’s band of pro-slavery men at Hickory Point, proceeded to that location, arriving on the 13th.

Captain Robertson, of Atchison, had in the meantime started with his company for Lecompton. Stopping at Hickory Point he was prevailed upon by Captain Lowe to remain there and help defend the place from Colonel Harvey’s proposed assault, news of which had reached him. The Pro-slavery forces defended themselves for three hours during the first day’s battle, which took place on the 13th. They were divided into three parties, entrenched in a blacksmith shop, in a hotel, and in a store, each about a quarter of a mile apart. The Atchison leader stood the brunt of the affray, as the shop in which he was fortified was an open log building, and he was considered Colonel Harvey’s most formidable opponent. Sam Dickson, of Captain Robertson’s command, had a narrow escape from death, and C.G. Newall and A. J. G. Westbrook had horses shot from under them. The next day, Sunday, September 14, at 10 a.m., Colonel Harvey resumed the attack, having obtained a four-pound cannon. He did such damage that the force of pro-slavery men capitulated and C.G. Newall was killed. News of this disobeying of orders had already reached Governor Geary, and on the night of the second day’s battle he dispatched a force of dragoons who made Colonel Harvey’s command prisoners. They were then indicted for the murder of C.G. Newall, tried, sentenced to hard labor, escaped, and were finally pardoned.

The reign of terrorism had been so well maintained by the pro-slavery party that up to early in the summer of 1857, there was no organization of Free-State men in the county. Several meetings were held in localities outside of Atchison, and a society was formed in the summer of that year at Monrovia, with F.G. Adams as Chairman of the County Committee. The Squatter Sovereign had been turned over to F.G. Adams, Senator Samuel Pomeroy, and Robert McBratney, prominent members of the New England Aid Society, which had been rapidly expanding its influence for the three years during which it had been in existence. Senator Pomeroy was the avowed agent of the society, and as the Town Association had made so positive a compromise with the Free-State party, for the business good of Atchison, Adams naturally supposed that the pro-slavery men would even take a dose of General James H. Lane. He accordingly invited the powerful leader of the Free-State men to speak in Atchison on October 19th, and circulated notices of the meeting.

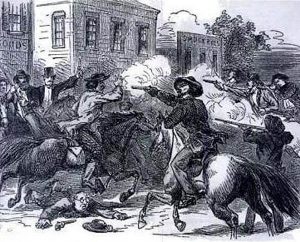

However, Adams had underestimated the people from Atchison, among whom it was generally understood several days before the appointed time, that Jim Lane couldn’t and shouldn’t speak in that town. In response, Adams invited about a dozen of his strong and reliable Free-State friends from Leavenworth to come up to Atchison to make sure there was fair play. They came, revolvers and all, arriving in the morning, and making their headquarters at the office of Adams, Swift & Co. While there with his friends, Mr. Adams noticed that a crowd had gathered on Commercial Street, about two blocks west. He, with six others, started for the scene of what appeared to be a disturbance. On their way, they met Caleb A. Woodworth, Sr., going down the street, bareheaded and apparently in trouble. Adams turned about, as he had passed them, to make inquiries and was immediately assaulted with a heavy blow on the cheek. He did not turn the other cheek, but drew a small pistol from his pocket and turned upon his assailant. The man who had assaulted him was accompanied by a squad of friends, all armed with guns who seemed bent on mischief, if not blood. A friend knocked down Adams’ hand, and cried “Don’t shoot yet!” Out came the revolvers, all aimed at the bold musketeers. This determined action was so unexpected, that the pro-slavery men withdrew to consider, and the Free-State men returned to their headquarters.

Adams then proposed to organize an outdoor meeting, the pro-slavery party having joined the Free-Staters again and every moment getting noisier and more desperate. A. J. W. Westbrook of the Atchison Guards rode around among his followers, with his gun cocked, pretending to have a vast amount of blood in his eye for the chairman of the Free-State County Committee. Now and then to give the “blood-curdling” feature to the proceedings the fellow would order the crowd to “get out of the way,” as he did not want to shoot the wrong man. It is doubtful whether Westbrook really intended to do much himself, but his conduct had the effect of stirring up his followers, who swore that Jim Lane should never speak. The Free-State Party, reasoning that it was not imperative to the cause that Jim Lane should speak, decided to postpone the meeting. So George Buell, now General Buell, took Adams by the arm and led him off home. Some of the Free-State party met General Lane on his way from Doniphan, where he had spoken the day before, and turned him back.

In the evening of this day, speeches were made by several citizens of various political stripes – Mr. McBratney, Dr. John H. Stringfellow, and others — all deprecating the disgraceful proceedings. They were not countenanced by any citizens of standing in the pro-slavery party. The whole affair was one of those outbreaks of the mob spirit, so common in those days. At this time, the brains of the pro-slavery party had given up the fight and would fraternize with anyone who would come in to help build up the town, now striving against other new and flourishing places around it.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated June 2020.

Also See: