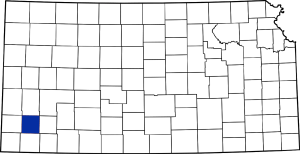

Situated on the High Plains in the far southwestern part of Kansas, Grant County was created in 1887 out of Hamilton County territory by an act of the Kansas Legislature and named in honor of General Ulysses S. Grant.

Long before the county was formed, numerous travelers passed through the area along the Cimarron Branch of the old Santa Fe Trail. Mostly prairie, these hardy pioneers traveled along the Cimarron River, which, unfortunately, was dry most of the time, even back then.

The Santa Fe Trail entered what was later to become Grant County midway of its eastern boundary. It continued its southwesterly course, crossing the North Fork of the Cimarron River, before reaching the well-known “Lower Springs,” later known as the “Wagon Bed Spring” on the Cimarron River. The Jornada stretch was a dangerous route for both men and animals in the dry season as the wagon trains often ran out of water, and their arrival at the oasis of Wagon Bed Spring was a welcome relief.

Grant County is the second county north of the Oklahoma line and the second east of Colorado. When it was created in 1887, the census counted 2,716 people, 653 of whom were householders.

George Washington Earp was the mayor of Grant County and a constable of Ulysses, Kansas.

When Grant County was first established, there were two candidates for the county seat — Ulysses and Tilden (later called Appomattox.) The governor’s proclamation was not made until June 1888, when Ulysses was named the temporary county seat and appointed county officers. The county is divided into three townships — Lincoln, Sullivan, and Sherman. Some of the first post offices were established in the now-extinct towns of Shockey, Gognac, Lawson, Waterford, and in the county seat of Ulysses.

A few months later, an election was held to determine the permanent location of the county seat on October 16, 1888. The voters had to decide between Ulysses and Tilden (later called Appomattox), and the county seat fight was fierce. At that time, George Washington Earp, cousin to the more famous Earp brothers, was the mayor and constable of Ulysses. According to legend, George Earp was just as “free with his gun” as Wyatt and his bunch.

George Earp would later say that the Ulysses Town Company imported several noted gunmen “to protect the security of the ballot” at the elections. Among them were Bat Masterson, Luke Short, Ed Dlathe, Jim Drury, Bill Wells, and Ed Short. The men built a lumber barricade across the street from the polling place, stationing themselves behind it with their Winchesters and six-shooters in case of trouble or attempt to steal the ballot box. But no trouble erupted, and in the end, the election resulted in a win for Ulysses.

But, like many other Kansas Counties, the fight wouldn’t end there. With corruption charges, the fight went to the Kansas Supreme Court, where evidence was submitted by a Tilden partisan named Alvin Campbell. He introduced facts to show that the city council of Ulysses had bonded the people to $36,000 to buy votes, claiming that the total votes paid for were 388.

It was an “open secret” that votes were bought, and “professional voters” had been brought in and boarded for the requisite 30 days before the election and given $10 each when they had voted. However, it was unknown then that this had been done at public expense. It was also alleged that “professional toughs” were hired to intimidate the Tilden voters.

The exposure of the fact that public funds had been used created excitement among the county’s citizens, who found themselves subject to the payment of bonds. Those to blame for the outrage retaliated against Alvin Campbell by tarring him in August 1889.

It was also shown in court that Tilden had bought votes and engaged in irregular practices, and Ulysses finally won, though it was a dearly bought victory. Added to the $36,000 spent in the county seat fight was $13,000 in bonds, which had been voted for a schoolhouse, and $8,000 for a courthouse.

At the height of the county seat contest between Ulysses and Appomattox in 1888, Ulysses boasted a population of 2,000. He supported 12 restaurants, four hotels, several other businesses, six gambling houses, and 12 saloons.

Ultimately, Ulysses was the victor in the Kansas Supreme Court in 1890 and has since retained its county seat status.

But the troubles weren’t over. In 1898, the county suffered from severe crop failure, causing panic and reducing the population from 1,500 to 400 in Ulysses and later to some 40 souls. Buildings were moved away, banks closed, and merchants let their stock of goods run down.

However, good crops returned the county to prosperity in the next few years. A new bank was opened, new buildings were erected to replace those moved away, and by the turn of the century, Ulysses boasted some 422 residents.

Several streams and rivers run through the county, including the Sand Arroyo Creek, which joins the North fork of the Cimarron River in western Grant County. The two forks of the Cimarron wander around and come together in the southeast part of the county. However, this did not ensure there was plenty of water, as these waterways were often dry. As a result, Grant County was one of the first in Kansas to utilize irrigation.

At a special legislative session in 1908, Kansas passed an act authorizing the county commissioners to appropriate money to drill artesian wells for irrigation purposes. This created further prosperity and large farms, even though the area doesn’t get much rainfall.

All was going well for Ulysses except for the old debt, which hung like a weight on the town. The bonds, due in 1908, amounted to $84,000 with accrued interest. Of the citizens of Ulysses, only two remained in the town from the time the county seat was established, and the newcomers could not see the justice of their having to pay a debt from which they derived no benefit. So, in 1909, the citizens decided to move the town. A new and better site was selected, about halfway to the old site of Appomattox, which had, in the meantime, become a field.

Moving the whole town was not light work, including the Edwards Hotel with 35 rooms, a bank, a printing office, several fair-sized stores, and several residences. Moving outfits were brought in from Garden City and St. John to do the heaviest hauling, while several local teamsters handled the lighter work. Only a masonry school was left behind for the East Coast bondholders.

Due to damage to the bank building, the safe sat out in the street for several weeks without being disturbed. The courthouse was left on the old site, and the county officers continued to do business there. The schoolhouse was not moved, so the people did not take with them any of the “benefits” for which the town had been bonded. The relocated town was then called New Ulysses, and the old townsite was referred to as Old Ulysses.

By 1910, the population of Ulysses had grown to 1,087 people, and when the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad extended to the county, it brought more prosperity. On June 9, 1921, the post office officially changed its name from “New Ulysses” to Ulysses.

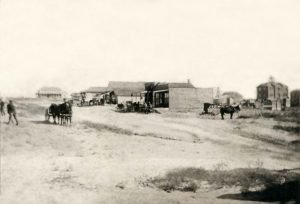

Ulysses, Kansas, in 1909.

In 1922, the Hugoton Natural Gas Field was discovered near Liberal, Kansas. However, it wasn’t developed for several years, as it did not produce oil. However, that changed in 1927 when the first company began to produce gas and by the following year, five wells had been drilled, and the first pipeline began transporting gas to local markets. The fifth-largest gas field in the United States was named for the nearby town of Hugoton, Kansas. Today, approximately 11,000 wells produce gas and oil in the region, and thousands of miles of pipelines carry the gas to many parts of the nation. Grant County has offices for many of the significant gas production companies in the United States.

In 1930, the county built a new courthouse to replace a wood frame structure that had been used since 1888. The building combines classical forms with Art Deco styling, with linear projections, terra cotta ornamentation, and decorative brickwork. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002.

The 1930s also brought the “Dust Bowl days,” and Grant County suffered terribly like many other areas of the High Plains Region. On April 14, 1935, the county was engulfed by a massive wall of black dust. Known as Black Sunday, the region went from daylight to total darkness in just one minute. Farmsteads, fence rows, and homes were covered with dust when it cleared, and the trees were stripped bare. Afterward, many deserted their farmsteads, heading for better climates. However, more persevered, determined to save the farms and homes. From 1930 to 1940, the county population reduced by 37%, from 3,092 to 1,946.

On December 17, 1936, citizens got good news when an announcement was made in the local newspaper that Grant County was to become a manufacturing center. Early in 1937, the Peerless Carbon Black plant became the county’s first gas-related industry. This sparked off more drilling, with about 40 wells completed by the end of that year. Grant County was moving into a new era.

Soon, the population began to grow again, and by 1950, the county was called home to 4,538 people.

Over the decades, growth remained steady, and today, Grant County supports about 7,300 people.

Though Grant County once supported more than a dozen towns, only three remain today: Ulysses, Hickok, and Ryus. The latter two are unincorporated and very small.

Encompassing 24 square miles of mostly flat land, the county boasts some of the nation’s most spectacular sunrises and sunsets. Situated on the High Plains, the area is also home to deer, pheasants, wild turkeys, coyotes, rabbits, and other wildlife, and hunters come from around the world to partake of the excellent deer and pheasant hunting.

The passenger depot, initially built by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad but utilized by the Cimarron Valley Railroad in Ulysses today, still stands. However, passenger service is no longer provided.

The Grant County Museum, situated at 300 East Highway 160 in Ulysses, provides the area’s history. The museum is housed in an old County Shop building initially built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1938. The museum features historical artifacts and exhibits that tell the story of life on the High Plains, including Indian artifacts, Santa Fe Trail memorabilia, and information regarding both old and new Ulysses. The museum complex also displays the old 1887 Hotel Edwards that was moved from “Old Ulysses,” as well as a one-room schoolhouse. It is open daily.

About 12 miles south of Ulysses, the old site of Wagon Bed Spring, which was situated along the Santa Fe Trail, can still be seen and is a National Historic Landmark today.

If you can add additional information or photographs regarding this article, please feel free to email us. We welcome updates and additional information.

More Information:

Grant County Kansas

108 S. Glenn

Ulysses, Kansas 67880

620-356-1335

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated August 2024.

Also See:

Ulysses, Kansas – Born Twice and Still Kickin’!

Wagon Bed Spring – On the Santa Fe Trail

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Grant County History

Kansapedia