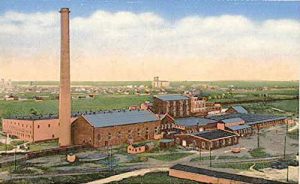

Co-operative Refining Co. in Chanute, Kansas, 1907.

The Earliest Kansas Farmers. Agriculture, our state’s leading industry, was almost our people’s only occupation for many years. The Indians were the first farmers in Kansas. The Comanche were roving hunters in the western part of the state, but the eastern Indians had permanent homes and tilled the soil. They were both hunters and farmers. In describing their mode of living, a government agent said: “They raise annually small crops of corn, beans, and pumpkins. They cultivate entirely with the hoe, in the simplest manner. Their crops are usually planted in April and receive one dressing before they leave their villages for the summer hunt in May.”

Agriculture Taught to the Indians. When Kansas was made an Indian country, the National Government agreed in the treaties to supply the Indians with cattle, hogs, and farming implements and to employ persons to teach them agriculture. Under this agreement, several government farms were established, and government farmers and missionaries taught agriculture to Indians. When Kansas was organized as a Territory in 1854, several farms were located on various reservations and at missions. The produce indicated that Kansas soil was remarkably fertile.

Agriculture During Territorial Days. Most of the early settlers of Kansas were farmers, but during the Territorial period, political and governmental turmoil made much progress in farming impossible. The severe season of 1860 marked a dreary conclusion to this period. It confirmed in the minds of many eastern people that Kansas was fit only for Indians, buffalo, and prairie dogs.

Agriculture During the Civil War. The year following the drought brought a good crop but also the beginning of the Civil War, which absorbed the settlers’ energies for four more years. It was not until the close of the war, in 1865, that agriculture could be said to have had an absolute beginning in Kansas. Despite the poverty and hardships of the war years, two developments of particular significance demonstrated the pioneers’ interest in agriculture. The Agricultural College at Manhattan was established during this period, and the State Agricultural Society was formed.

The object of the Society was “to promote the improvement of agriculture and its kindred arts throughout the State of Kansas.” Under its management, a state fair was held in Leavenworth in 1863, and that year the Legislature appropriated $1000 for the benefit of the Society. These events are noteworthy because they demonstrated the people’s enterprise despite limited resources. Early Farming- Implements. The farming implements of the pioneers were few and simple. Much of the machinery of today had not then been invented. Because of transportation costs and the lack of money among the settlers, even the machinery of that day was scarce in Kansas. The all-important implement was the plow. The pioneer’s first crop was usually “sod corn.” The field was prepared with a breaking plow, which threw the sod in parallel strips from two to five inches in thickness.

Then the farmer, with an ax or a spade and a bag of seed corn, walked back and forth across the field, prying apart or gashing the sod at regular intervals and dropping into each opening three or four grains of corn; then he waited for the crop. Once the land was broken, the seed was prepared with a stirring plow and a harrow, and planting was performed with a hand planter. Later, the corn planter drawn by a team came into use. This machine required a driver and another person to work the lever that dropped the corn. Then came the planter with the check rower, which made only a driver necessary when attached to the planter. The lister has become widely used in the last few years. The early settlers cultivated corn with a single-shovel cultivator drawn by a single horse. With this cultivator, it was necessary to trip along both sides of each corn row. The double-shovel cultivator soon came into use, but it was also drawn by one horse and cultivated only one side of the row at a time. This labor was significantly reduced by the invention of the cultivator, which was drawn by a team and had shovels for both sides of the cornrow. Formerly, the farmer cut all his corn by hand with a knife. He now used the corn binder.

As corn machinery has improved, even more significant changes have occurred in wheat-crop machinery. The earliest harvesting implement used in Kansas was the cradle, a scythe with long fingers parallel to the blade to catch the grain as it was cut. The cradler laid the grain in rows. A second man followed with a rake and gathered the wheat into small piles, which he tied into bundles, using some of the straw for bands. The next machine was the reaper, which carried two men to drive the team and push off the wheat whenever enough had been cut to make a bundle. The reaper required four or five binders to follow it. It was soon improved by being made self-dumping and, later, self-binding. Inventions and improvements have followed in rapid succession, and today, the planting and harvesting of wheat can be done with remarkable speed and efficiency. The numerous advances in farm machinery have enabled significant time and labor savings in today’s farming compared with 40 years ago. There are a few lines in which more significant progress has been made.

Agriculture Between 1860 and 1880. For several years after the Civil War, Kansas’s population grew more rapidly than its crops, keeping the state poor. The destruction of crops by the grasshoppers in 1874 retarded immigration and left the people discouraged. However, several good crop years followed, and confidence in Kansas’s agricultural future soon returned. By 1880, nearly 9,000,000 acres of land were in cultivation, a third of which was planted to corn and a fourth to wheat. The next most extensive acreage was in oats. Several other crops were reported, including rye, barley, buckwheat, sorghum, cotton, hemp, tobacco, broom corn, millet, clover, and bluegrass. At that time, little was known about the state’s soil or climate; in this list of crops, several have since proven unprofitable and are no longer raised in any considerable quantities.

Agriculture from 1880 to 1887. In 1880, the people of Kansas were full of hope and courage, and from that time until the drought of 1887, agriculture developed rapidly. It was a period of new ideas and new methods. Millions of additional acres were brought into cultivation. The principal crops, corn, wheat, and oats, increased significantly. Fields of timothy grass, clover, orchard grass, and bluegrass were planted in the central counties and even farther west. Soil that had been considered unfit for farming a few years before produced crops. The state was being rapidly settled, many miles of railroad were in operation, and the excellent crops encouraged the “boom” of 1885 to 1887.

Agriculture from 1887 to 1893. The period of good crops following the dry season of 1887 lasted five years and was marked by significant activity across many areas of agricultural advancement. By 1890, nearly 16,000,000 acres had been brought under cultivation. This area was almost double the area under cultivation ten years earlier.

Western Kansas. Before 1890, most farming was conducted in the eastern and central parts of the state, with the western part considered poorly adapted to agriculture. However, over the next few years, it was shown that wheat could be successfully grown up to the Colorado line. Sorghum crops also proved well adapted to this region. The soil of western Kansas was highly fertile, requiring only moisture to produce abundant yields. A more thorough understanding of soil and climate led to improved tillage methods, and this, together with careful crop selection, increased yields and made them more reliable.

Irrigation in Western Kansas. The irrigation potential for this region has long been considered. For several years, water from the Arkansas River was successfully used. In developing irrigation, Colorado used so much water from the upper Arkansas River that there was not enough left for our state. The investigation revealed an underground water supply. This water, called the underflow, moves eastward from the Rocky Mountains through gravel- and sand-bearing strata.

It provides a large portion of western Kansas with a practically inexhaustible water supply for irrigation. Wells are bored into this underflow, and the water is pumped for irrigation. Only a small part of western Kansas is under irrigation in the early 20th century. However, experiments to find individuals, experiment stations, and the state, using the best methods of underflow, increased irrigation in the state, and irrigation by pumping brought about a remarkable agricultural advancement in western Kansas.

Alfalfa. About 1890, several new crops became prominent in Kansas, the most important of which was alfalfa. Alfalfa began to grow in every Kansas county and became one of our foremost crops. Because of its long, penetrating roots, it can be grown successfully without irrigation, even in most of the drier parts of Kansas. As its many points of excellence became better known, its acreage constantly increased. Within a short time, Kansas produced more alfalfa than any other state. Sweet clover and Sudan grass increased in acreage to such an extent that they rapidly became important crops in this state.

The Sorghum Crops. Another of the new crops was Kafir corn, which has also proved very valuable. This plant is a sorghum variety. Other varieties had been raised in Kansas for many years, particularly sweet sorghum, which could be used to produce sugar and molasses. Broom corn is another sorghum crop grown in Kansas for a long time and raised in large quantities in the southwestern part of the state. In recent years, two more sorghums, milo and feterita, have promised to become valuable forage crops.

Sugar Beets. During the early 1880s, considerable sugar was produced from sorghum cane, but in 1889, it was produced from beets for the first time. Experiments were made with sugar beets in different parts of western Kansas for several years. The state offered a bounty to encourage the cultivation of sugar beets, and many tons were produced and shipped to sugar factories in Colorado and Nebraska. In 1906, a large factory was completed in Garden City, and the raising of sugar beets became an important industry in that part of Kansas. Efforts were then made to introduce this crop into other parts of the state.

The Twenty-five Years Following 1893. Progress was checked in 1893 by the financial panic that spread nationwide. Prices declined, and prices were low for everything the farmers had to sell. In addition to the panic, Kansas suffered a crop failure in most of the state. That was a discouraging period, but within a few years, Kansas had recovered. Subsequently, all values increased steadily. Land prices steadily rose due to the fact that there was no longer any free land to be taken as homesteads. The price of land products also significantly increased. In 1893, corn was priced at 10¢ to 15¢ per bushel, and wheat at 30¢ to 40¢ per bushel.

Kansas Wheat. By the 1920s, Kansas was one of the leading agricultural states in the country. It produced a greater variety of crops than almost any other state, but the principal ones were, as they have been from the earliest days, corn and wheat. Alfalfa came to be a close third. Wheat was our most noted crop, and Kansas was unsurpassed in producing this grain. Wheat is grown in every county in the state, but by far, the most significant quantity comes from the “wheat belt,” which extends across the middle of the state, from north to south. Most Kansas wheat is of the winter varieties commonly called “Turkey wheat,” first brought here from southern Russia by the Mennonites in 1873.

The Corn Crop. Corn was cultivated here by Native peoples, and from the Territory’s settlement until the early 20th century, it was the leading crop and the most significant source of Kansas wealth. Since 1913, however, wheat has become the state’s most valuable crop, and corn has had to take second place. Corn is grown throughout the state, but the largest share is produced in the eastern half. Kansas’s great livestock industries depend on this crop most of the time.

The Livestock Industry. The livestock industry is one of the state’s most important interests. The grain and forage crops, the large areas of good pasture, the plentiful supply of water, and the nearness to market all combine to make Kansas an excellent livestock region. The raising and fattening of cattle and hogs constitute the chief features of this industry, although there are several others, prominent among which is dairying. Early farmers maintained herds and flocks but paid little attention to quality or breed. Over time, it was found that higher grades were more profitable, and the early-range cattle and the pioneers’ scrub stock disappeared.

When the Union Pacific Railroad was built, Texas cattlemen began driving their cattle into Kansas for shipment to market. For many years, Abilene was the shipping center. When the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad was built, Wichita became the chief shipping point because it was farther south. The cattle trade was pushed farther west as the country was more settled. Finally, it reached Dodge City, which remained the shipping center for many years. The construction of railroads into the Southwest made it unnecessary for Texas cattlemen to drive their stock to a Kansas shipping point, and in about 1885, the practice was abandoned. While the trade flourished, the cowboy, with his boots, spurs, and broad-brimmed hat, was a familiar figure on the plains of western Kansas; as settlers converted grazing land into farms, the cowboy moved farther west.

Horticulture. Another Kansas industry is horticulture, which is the cultivation of fruits. The first orchard in Kansas was planted at Shawnee Mission in 1837. However, minimal tree planting occurred until after the Civil War, and even then, the Kansas plains were regarded as unsuitable for fruit production for many years. The early crops were small but of fine quality, and Kansas apples won the gold medal at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876. This aroused considerable enthusiasm, and over the next few years, many thousands of fruit trees were planted; however, most proved worthless because the varieties were not adapted to the state’s conditions. Long years of hard work and patient effort were required to secure the knowledge necessary to make a prosperous state of Kansas. Many fruits were grown here by the early 20th century, but the Kansas apple was famous. Scarcely a farm in the eastern and central parts of the state was without its orchard, and several commercial orchards made horticulture an essential industry in Kansas.

Farmers’ Organizations. State farmers formed several organizations over time, particularly in the early years. An early organization was the Order of Patrons of Husbandry or the “Grange,” a national movement introduced in Kansas in 1872. Its general purpose was the improvement of farm life. Many Granges were organized during the 1870s. The Farmers’ Cooperative Association, established in 1873, and the Farmers’ Mutual Benefit Association, established in 1883, had, as their general purposes, the cooperation of farmers in buying and selling and in securing lower freight rates.

In about 1888, the Farmers’ Alliance, already a national organization, formed many local organizations in Kansas. The Alliance demanded several measures to benefit farmers, including lower freight and passenger rates and improved mortgage, debtor, and tax laws. The Farmers’ Alliance was a widespread movement and, for a time, overshadowed all other farmers’ organizations. In 1890, the People’s Party, or the Populist Party as it came to be called, assumed the potential work of the Farmers’ Alliance, and that organization gradually disappeared. The Farmers’ Educational and Cooperative Union of Kansas came later.

The State Board of Agriculture. In 1872, the Agricultural Society, organized during the Civil War, was changed into the State Board of Agriculture. For several years, this Board gave special attention to gathering and distributing information concerning the state’s resources to stimulate immigration. Later, it began providing farmers with information on farming methods best adapted to Kansas conditions. These activities continued, and the Board of Agriculture was of great practical value to the state.

Work of the Agricultural College. The Agricultural College (Kansas State University today), in its early years, placed little emphasis on agricultural and industrial work. However, in 1873, its work plan was changed, and it soon began to fulfill its fundamental mission. A few years later, the usefulness of the College was significantly increased by the establishment of an experiment station where investigations are carried out in such matters as the testing of seeds, the introduction of new crops, the rotation of crops, dairy and animal husbandry, butter and cheese making, orchard and crop pests, stock foods, and diseases of livestock. In later years, branch experiment stations were established at Hays, Garden City, Dodge City, Tribune, and Colby, where problems peculiar to the western part of the state are studied. The Agricultural College was gathering information and disseminating it to the public through bulletins, lectures, correspondence courses, demonstration trains, demonstration agents, and farmers’ institutes. Kansas was one of the first states to hold a Farmers’ Institute in connection with its Agricultural College. This work was begun in 1869, and its purpose, as it is today, was to promote knowledge of scientific agriculture.

Manufactures Based on Agriculture. Kansas’s agricultural resources have led to the development of several manufacturing industries. One of the oldest of these is milling. Among the first needs of the settlers of the new country was a means of grinding their corn and wheat into meal and flour for family use. This led to the construction of small gristmills in every community. Most of them were built along streams and powered by water, though a few early ones used wind. In later years, steam has generally been used. After the introduction of hard wheat, the wheat crop became more reliable, acreage increased, and the milling industry expanded. Kansas flour is now sold in all the world’s important markets, and Kansas is one of the leading states in the milling industry.

Meatpacking has held first place among Kansas’s manufacturing industries for decades. Kansas City, once the second-greatest packing center in the United States, was the chief market for Kansas livestock for many years. Still, several packing houses were located in different parts of the state. Creameries, canning factories, and pickling works represent other industries that have been developed to use our agricultural products.

The Mineral Industries. Although Kansas is not one of the great mining states, it has several valuable mineral resources: coal, lead, zinc, oil, gas, salt, building stone, and gypsum. These resources form an essential part of the state’s industrial life. Coal and natural gas have enabled several manufacturing industries.

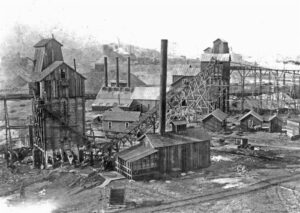

Coal. As early as the Territorial period, it was known that there were coal fields in Kansas, and small amounts of coal were mined in Crawford and Cherokee Counties. Immediately after the Civil War, settlers in the southeastern part of the state paid close attention to coal mining, some of which lay so near the surface that it could be uncovered with a plow. Within the next few years, coal was found in Osage and Leavenworth Counties and the vicinity of Fort Scott. These places produced large amounts, but Crawford and Cherokee counties soon became the state’s leading coal districts. In the 1910s, approximately nine-tenths of Kansas’s output was mined in these two counties. The importance of the coal fields of Kansas lies not only in the value of the coal but also in the stimulation of the growth of manufacturers. Many industries relied heavily on fuel to generate power. The development of several such industries in Kansas was made possible chiefly by the cheap and abundant coal supply.

Lead and Zinc. Before Kansas was organized as a Territory, lead mining was an important industry in southwest Missouri. Still, it was not until 1876 that it was discovered that the lead and zinc field extended into the southeastern corner of Kansas. Prospecting began immediately, and thousands of people were soon on the ground. Although zinc was abundant with lead, little attention was paid to it. Within a few years, however, it was found that the abundance of coal made the smelting of zinc profitable, and zinc soon assumed the leading place. For several years, zinc has been produced in much greater quantities than lead.

A large amount of ore from the Missouri mines was shipped to the Kansas smelters, and the smelting of lead and zinc, particularly zinc, became one of the most critical mineral industries. The development of the gas field provided a cheaper and more abundant fuel than coal, and much of the smelting was soon conducted where gas was available. In later years, gas was less abundant, and there was a tendency to return to the use

of coal.

Oil and Gas. Although prospecting had been done earlier, the actual development of oil and gas in Kansas began about 1892, with the discovery of the big Kansas-Oklahoma field. The oil and gas area is within an irregular strip, 40-50 miles wide, extending from Kansas City southwesterly into Oklahoma. It is often referred to as the “oil and gas belt.” By 1900, nearly every town in the gas belt had more gas than it knew what to do with, and various manufacturing enterprises, such as brick plants, zinc smelters, glass factories, and Portland cement mills, were soon attracted to these towns. Subsequently, gas was supplied to cities outside the gas belt. Pipelines were laid to Wellington, Wichita, Hutchinson, Topeka, Lawrence, Kansas City, Leavenworth, Atchison, and many other towns. After ten years of this significantly increased use of gas, the supply has become less abundant, and it is now feared that the supply from this field may fail in the near future.

In earlier years, oil was transported exclusively by tank cars, but a pipeline system was soon installed. Many refineries were soon established. Crude oil is used primarily for fuel and as machine oil. In the refineries, it is made into benzine, gasoline, and kerosene. Vaseline and paraffin are among the by-products. In 1914, oil and gas were discovered in Butler County. Within two years, this field yielded such large quantities of oil that the state’s total production doubled. In 1917, more than three times as much oil was produced as in 1916, and Kansas had become the largest oil-producing state in the Union. The output of the Butler County field continues to increase, and its remarkable yield will likely persist for several years.

Salt. Salt is found in Kansas as brine in salt marshes and as beds of rock salt beneath the surface. The marshes were known to early hunters and settlers, and, in the early years of statehood, a small amount of salt was produced from this brine. In the late 1880s, rock salt beds were discovered, and the salt-making industry was rapidly developed. The center of the salt industry is now, as it has been from the beginning, at Hutchinson. Salt is found in many parts of Kansas, but the most valuable area extends north-south across the state’s middle. In most places, this great salt bed is from 250 to 400 feet thick. Some salt is produced by crushing rock salt, but evaporation accounts for a larger share of the brines. The brines are obtained by forcing a stream of water through rock salt.

Brick. Brickmaking in Kansas dates from the early years. Brick clays are found in many parts of the state, but the industry is carried on chiefly in the eastern part of the state, especially in the gas belt, because of the fuel supply.

Gypsum. Gypsum beds are found in central Kansas, especially around Blue Rapids and Saline, Dickinson, and Barber Counties. Plaster of Paris, used primarily for covering wall surfaces, is made from gypsum.

Portland cement is a comparatively new product in the United States. The development of this industry in Kansas began around 1900. Portland cement is made from certain mixtures of rock substances that are ground and heated. Its chief use is in producing concrete, which is widely used in construction. There were several Portland cement mills in the gas belt.

Glass. Gas is the most suitable fuel for glassmaking, and since the Kansas gas field was opened, several glass factories have been established in the state. Good-quality sand for making glass is also found in southeastern Kansas.

Agriculture: The Basis of Material Progress. In 1920, many Kansas factories engaged in a variety of lines of work. Our industries are continually expanding in number and importance, and they all contribute to a well-rounded state. However, the agricultural sector underpins our prosperity.

Summary. The state’s principal agricultural industries are farming, stock raising, and horticulture. The principal mineral industries were coal, lead, zinc, oil, gas, salt, building stone, and gypsum. The leading manufacturing industries are primarily concerned with agricultural and mineral products, which are produced most extensively in the coal and gas regions. Droughts in all agricultural regions have been most severe in Kansas in the following years: 1860, 1869, 1874, 1887, 1893, and 1913. These years have marked periods of otherwise steady progress in agriculture.

The Agricultural Society, organized during the Civil War, was changed into the State Board of Agriculture in 1872. The Agricultural College, established during the Civil War, began active work in agriculture in 1873. Several farmers’ organizations have existed, most of them between 1870 and 1890. Agriculture has advanced in areas such as increased under-cultivation, crop selection, machinery improvements, and improved tillage and irrigation methods. The leading crops in 1920 were corn, wheat, and alfalfa.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2025. Source: Arnold, Anna E.; The State of Kansas; Imri Zumwalt, state printer, Topeka, Kansas, 1919.

Also See: