Like other eastern parts of Kansas, Johnson County was caught up in border troubles with Missouri after Kansas Territory was created and into the Civil War.

The first election held in Kansas Territory was in the fall of 1853, before the Territory had even been organized. At the election, Indians and whites were allowed to vote, even though they were not citizens of the United States and had no right to vote. This was an unfortunate beginning for the future Territory and the State of Kansas. When the question of Territorial organization was unsettled, almost everyone in the Indian missions and elsewhere, government agents and employees, missionaries and teachers, were all but universally Democratic and Pro-slavery. The Indians imbibed and carried into practice the political views of their teachers — religious and secular. The principal exception to this rule was the case of the Quakers, who were consistently anti-slavery.

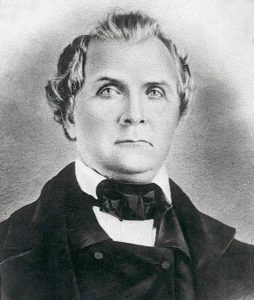

At this election, Reverend Thomas Johnson, a slaveholder in charge of the Shawnee Mission in Johnson County, was elected as a delegate to Congress to urge the organization of the Territory. However, because he was elected without the authority of law, he was not admitted to a seat as a delegate. However, he remained in Washington, D.C., during the session until after the Kansas-Nebraska Bill became law in May 1854.

The first official election was held on March 30, 1855, for the First Territorial Legislature members. Reverend Thomas Johnson was elected from Johnson County to the Senate and his son, Alexander S. Johnson, to the Legislature. The Legislature was convened at Pawnee, near Fort Riley in present-day Geary County, and organized by electing Reverend Thomas Johnson, President of the Senate, and Dr. John H. Stringfellow, Speaker of the House. Almost immediately after the organization, an act was passed locating the Territory’s capital at the Shawnee Mission, and the Legislature adjourned.

On July 16, 1855, one of its first acts was the organization of the settled portions of the Territory into counties. Johnson County was named in honor of Reverend Thomas Johnson. Bills were passed to lay out towns and villages in various counties, but none were passed in Johnson County, as the Shawnee reservation entirely covered it. Isaac Parish was appointed Sheriff of the County, and William Fisher, Jr., Probate Judge. Johnson County was thus organized and officered nearly two years before any of its lands came into the market and before any white people except those connected with the Indians were allowed to reside in it.

At this session of the Legislature, the Santa Fe Trail, passing through the center of the county, was declared a Territorial road; a road was located through the northern part of the county to Lawrence, Lecompton, and Fort Riley, and another along the eastern line of the county from Westport, Missouri, to Fort Scott, Kansas.

On October 23, 1855, the Free-State Constitutional Convention assembled at Topeka, Kansas. Johnson County was not represented, as its people were intensely pro-slavery. The convention adopted a constitution, the most important feature of which was a clause prohibiting slavery in the State. On December 15, the Topeka Constitution was submitted to the people and received a sizeable popular vote outside of Johnson County.

This Legislature was summoned to meet at Topeka on July 4, 1856. However, when the members assembled, they were not permitted to organize and were dispersed by Colonel Edwin V. Sumner, acting under orders from President Franklin Pierce.

During the summer, Joel Grover attempted to organize a company within the county to act with the Free State men, but owing to the limited number in the county who sympathized with the cause, the attempt was abandoned.

In August 1856, a party of border ruffians went to the Quaker Mission. After threatening to kill the superintendent, Jeremiah Hadley stole six horses, a mule belonging to the Mission, and a carriage owned by Levi Woodard.

This same year, a remarkable battle was fought in the western part of Johnson County. Being fought on Bull Creek on September 1, 1856. General James Lane met the Pro-slavery forces under General Reid, where the village of Lanesfield was located. Lane’s forces numbered about 400, while Reid’s were about 1,500. After skirmishers had exchanged a few shots on either side, Reid ordered his men to fall back. This order was obeyed with enthusiasm, and the men, panic-stricken, fell clear back to Westport, Missouri, a distance of 30 miles, without stopping to rest their tired steeds. After the fight, General Lane’s men burned the residence of Richard McCamish in retaliation for his having taken part in the fight under Reid.

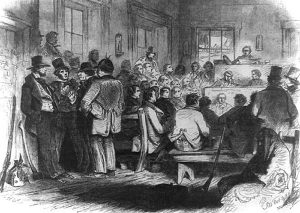

Perhaps nothing more clearly shows the purpose of the slavery supporters and their utter and wanton disregard of the principles of right and liberty than the records of early elections in a small precinct named Oxford, in Johnson County, near the Missouri line, containing eleven houses. On October 5, 1857, an election was held for Councilmen, Senators, and Representatives in the Legislature. On October 19, Governor Robert J. Walker issued a proclamation rejecting the full return from the Oxford precinct. This return was a manuscript 50 feet long, containing 1,628 names, mostly of imaginary voters. The next day, a Democratic meeting was held at Lecompton, and Major G. D. Hand of Johnson County was the secretary. The meeting passed a long series of resolutions severely condemning the Governor for his actions in this matter. Had the return been admitted, it would have changed the party character of the Legislature, transferring from the Free-state to the Pro-slavery side three Councilmen and eight Representatives. On December 21, 1857, an election was held on the Lecompton Constitution. Oxford precinct again distinguished itself by casting 1,214 illegal votes. Shawnee cast 729 illegal votes in this election. At this election, W. J. Sheraff, A. A. Cox, H. W. Jones, and J. B. Wiley were chosen as representatives in the legislature from Johnson County.

On January 4, 1858, an election was held for the election of officers under the Lecompton Constitution. Oxford precinct showed marked improvement over its other attempts, casting only 696 illegal votes. On January 29, an act of the Legislature took a census of Oxford, which showed that the precinct contained only 42 voters.

These were troublesome times in eastern Kansas. However, Johnson County incredibly escaped during this time but would suffer later. This escape was owing, doubtless, to the fact that the county was not open to settlement and that most of the few settlers here belonged to one political party. Still, a few incidents illustrate the character of the times.

On May 14, 1858, James Montgomery and a band of his followers surrounded the house of John Evans, a Johnson County farmer and a pro-slavery man living three miles northeast of Olathe. They warned Evans to leave the Territory within ten days forcing an entrance into the house. Evans replied that he would not go. Montgomery took about $800 in gold, besides other property belonging to Evans, a gold watch, and some money belonging to Patrick Cosgrove, who was Sheriff at the time and departed.

On another occasion, while John Lockhart, a Quaker man elected to the Free-State Legislature, and Calvin Cornatzer were on their way to Chillicothe, about three miles west of Shawnee, some armed Missourians overtook them, threatening to arrest them as being in sympathy with James Lane. But by clever explanations by Cronatzer himself and Dr. John T. Barton, who lived at Chillicothe, both Lockhart and Cornatzer were allowed to go free. These explanations did not remain satisfactory, however, for very long. A few weeks later, a squad of Missourians sought Lockhart at the Mission and searched the building thoroughly for him. He saved himself this time by slipping from one room into another. The same summer, Cornatzer was arrested at the insistence of two of his pro-slavery neighbors, who accused him of being a Jim Lane man. He was taken to Tecumseh and lodged in jail but was released the next day.

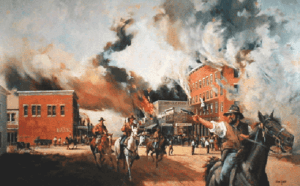

A re-creation of the Battle of Black Jack in which Pearson fought with John Brown. Photo courtesy Baldwin City Signal.

In addition to these comparatively mild experiences, some flagrant outrages were committed within Johnson County’s limits. One of these was the case of a young man named Jacob Cantrell, who had moved from Missouri to Kansas. A few days before his “trial” and murder, he had participated in the Battle of Black Jack on the Free-State side under old John Brown. He was taken prisoner by a party of Missourians under General John Whitfield, who was passing through Johnson County on their way to Westport, Missouri. They camped for the night about two miles west of Olathe and tried Cantrell for “treason to the State of Missouri during the evening.” He was then convicted and shot for his crime.

One of the most cold-blooded murders committed on the border was the shooting of William Gay, who was a Shawnee and Wyandot Indian agent. When on his way to Westport, he was stopped by pro-slavery men. When he admitted having sympathy for the Free State men, he was shot in front of his son near the Methodist Mission.

In April 1859, a proposition to hold a Constitutional Convention was submitted to the people of the Territory. The proposition was sustained, and the convention assembled at Wyandotte on the first Tuesday in March 1859. Johnson County was represented in this convention by Democrat Dr. John T. Barton and Republican Colonel John T. Burris. Colonel Burris was the first out-spoken Republican in this then-Democratic stronghold and the first Republican elected at a general election. On the first Tuesday in October, following, the constitution framed by the Wyandotte Convention was adopted by the people by a majority of nearly 4,000 — 10,241 for and 5,530 against it.

On January 29, 1861, Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state.

In April 1861, when the Civil War erupted, Johnson County, in common with other counties bordering on Missouri, had peculiar reasons for looking forward to the future with grave forebodings. Although peace had reigned for several years, it had been the peace of conquest on the one hand, of defeat on the other. The defeated party was just across the line in Missouri; the hearts of which party were filled with a smoldering hatred that needed but the first spark of war to rekindle it into flame and fury. When that spark was struck by the attack upon Fort Sumter, South Carolina, the exultation of this party was unbounded. They looked upon the North as cowardly, the South as invincible, and an easy victory as a logical sequence. They were fully determined to wreak vengeance upon their foes now that opportunity had come, and they had many foes in Johnson County.

Johnson County furnished its full quota of soldiers throughout the four long years of the war for the Union, who did their full share of noble fighting.

Battle of Blow-Hard

The name of the battle of Blow-hard distinguished the first battle of the war within Johnson County limits. It was fought in August 1861. The farmers between Olathe and Missouri had previously held a meeting at the house of Gabriel Reed and determined to station night patrols on the roads leading into Missouri. From the opposition of one of their number present, it was promptly inferred that he was a Rebel sympathizer.

Pat Cosgrove and Joseph Hutchinson went to Little Santa Fe on official business shortly after the meeting. They failed to return as expected, and it was learned the next day that they were held as prisoners in Missouri. A company of 100 men was soon organized, armed with almost every conceivable weapon, and marching with patriotic ardor on Little Santa Fe, fully determined to rescue the prisoners at whatever the cost. After marching about five miles, the company halted, sending forward two men to reconnoiter. While awaiting their return, the rest of the men spent their time speculating upon the number of ghastly rebel corpses that would bestrew the ground the next morning around Little Santa Fe unless those prisoners were surrendered on demand. While thus engaged, a long black line of horsemen was suddenly discovered approaching. Despite their bravado and the fate of the prisoners they had recently been so anxious to rescue, they instantly began to run back toward Olathe.

Upon reaching the summit of a ridge, they looked back, but their pursuers were not in sight. Some of them halted and hastily threw up a timber fortification, 60 feet square by two feet high. About 20 awaited the expected attack of the Rebels in this fortification while the remainder hastened on toward home. The Rebels did not attack. Upon investigation, it was learned that they had merely come out to escort Franklin and his family back to Missouri among their friends. The prisoners themselves soon returned, not having been harmed nor mistreated in any way. Thus happily ended the battle of Blow-hard.

Jennison’s Raid on Olathe

Shortly after the happy termination of this “Battle of Blow-Hard,” Charles R. Jennison and his Jayhawkers made a raid on Olathe. He had raised a company with a view to joining a regiment and then being organized at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, but he was not accepted, so he decided to do some independent work.

Arriving at Olathe in September 1861, his band arrested L. S. Cornwall, his partner, Drake, Judge Campbell, and the Turpin family, who were well-known Southern sympathizers. When Cornwall protested, Jennison struck him in the face with his pistol. Jennison released them after holding his prisoners for several hours, confiscating their weapons, and swearing them not to take up arms against the United States. They then went to Aubry township, where they robbed an old German doctor of a large sum of money and valuables. L. S. Cornwell and Drake left the county due to this raid, and Jennison was never punished for his arbitrary proceeding.

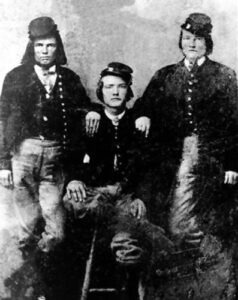

Bloody Bill Anderson Raids Olathe

The next trouble from across the line occurred on August 1, 1862, when bushwhacker “Bloody” Bill Anderson and two companions visited Olathe. Before reaching the town, they robbed and murdered a Mexican trader. They stopped at Charles Tillotson’s hardware store in Olathe and inquired about the road to De Soto, enforcing a truthful answer by holding a revolver at his head. Just at the edge of town on their way to De Soto, they met Deputy Sheriff Weaver, returning from a cow hunt, and “held him up,” but finding no valuables on his person, let him go. Weaver went at once to Sheriff John Janes, who started in pursuit. Janes caught up with Anderson and his companions a mile or two out of town and was promptly taken prisoner and disarmed. A few minutes later, they made prisoners of James Wells and another citizen. Releasing the latter, they took Janes into a ravine and told him that he would be shot but finally released him. On his way back to town, Janes met John and Ben Roberts, who had followed, thinking that harm had overtaken the sheriff. Janes and the Roberts boys had each a Sharp’s carbine. Finally, John Roberts succeeded in mortally wounding one of the trio, and he fell from his horse. Janes stopped to secure the wounded man. Another citizen joined the Roberts boys in the pursuit and shot one of the fugitives’ horses. The dismounted bushwhacker mounted behind his companion and attempted to escape but was soon wounded and surrendered. The third escaped to the brush but was captured that evening. The two men with Anderson gave their names as Lee and Coover. Coover was mortally wounded and died in a few days. He claimed to be a lawyer by profession and gave evidence of being a man of education and intelligence.

The next day a jury of 12 decided that the two remaining prisoners should suffer death. However, the crowd furnished no volunteers to execute the sentence, and Sheriff Janes settled the matter by taking the prisoners from the mob and locking them in jail. This offended John Roberts, and he took a shot at the sheriff as he stood in the upper front window of the jail. The shot missed him, but only by a few inches. Janes grabbed a musket and sent a ball and three buckshot after Roberts, who was making excellent time for the nearest corner. One buckshot hit Roberts in the thigh, and another hit him in the neck, but the wounds were not serious, and in a few days, the sheriff and Roberts talked the matter over and became friends again. The prisoners were sent to Leavenworth a few days later to be dealt with by the military authorities.

Before leaving Olathe, Anderson remarked to the citizens assembled to see him off: “Gentlemen, I will visit your town again,” and he did, for he participated in every border raid and, as a cold-blooded murderer, had no equal. He was killed at the close of the war.

On September 6, 1862, William Quantrill and his men raided Olathe. He had doubtless been informed of the defenseless condition of the town. When his band, consisting of about 140 men, approached Olathe, they killed a young man named Frank Cook, who had recently enlisted in the Twelfth Kansas. They also killed two brothers, John J. and James B. Judy, who had also enlisted in the Twelfth Regiment. Upon entering Olathe, the inhabitants were surprised as the raiders marched through the town, invaded the houses and stores, stole considerable property and goods, and corralled the citizens in the public square. In the melee, they shot and killed Hiram Blanchard of Spring Hill, who tried to prevent them from stealing his horse, as well as Phillip Wiggins and Josiah Skinner. After accomplishing his designs, Quantrill led his men back into Missouri with their plunder.

This raid was a severe check to the prosperity of Olathe, or perhaps it would be more correct to say, a powerful aid to its decline. Its businessmen had lost heavily by the raid, but little of the property stolen was ever recovered. The people felt insecure, being subject to raids by both friends and foes of the Union. Afterward, soldiers were stationed in the town for protection, and the citizens felt more secure.

Quantrill’s Raid on Shawnee

Emboldened by his success at Olathe, Quantrill repeated his experiment at Shawnee on October 17, 1862. A great deal of property was stolen at this place, and nearly the whole town burned down, 14 houses being entirely consumed and others considerably damaged by the fire. A Mr. Stiles and a Mr. Becker were killed in the town, and five others outside, one of whom was James Warfield and another an Indian.

Quantrill’s Raid on Spring Hill

In February 1863, George Todd, one of Quantrill’s lieutenants, attacked Spring Hill with ten men, taking the town entirely by surprise, as had been the case at Olathe and Shawnee. Although considerable property was stolen and destroyed, no murder was committed then.

More Atrocities

During the year, however, the people all over the county were in a state of continual alarm, as occasional depredations of some kind or murder would be reported. Among the citizens of the county shot and killed this year were William Reece, a Mexican trader, and one of his men, all in the vicinity of Indian Creek.

On August 21, 1863, occurred the Lawrence Massacre. Quantrill’s forces passed through Johnson County, camping near Aubry for supper on their way there.

The horrible massacre at Lawrence aroused the citizens of Kansas to renew efforts on behalf of the Union and the defense of their firesides. The Fifteenth Regiment of Calvary was raised immediately after the Lawrence raid. Charles R. Jennison, the notorious jayhawker who had been Colonel of the Seventh Regiment, was appointed Colonel of the Fifteenth. George H. Hoyt, a notorious Red Leg, was commissioned Lieutenant-Colonel, and John M. Laing, Major. This regiment was composed principally of veteran soldiers, veteran red-legs, and veteran jayhawkers, imbued with an intense hatred of the rebellion, brave even to recklessness, and animated with a spirit to avenge the great and peculiar wrongs of Kansas.

Quantrill and his men raided Olathe again on October 24–25, 1864, when Confederate Major General Sterling Price passed through with a force of 10,000 men on their retreat south. Later, General Price and his men were defeated at Mine Creek.

During the remainder of the war, the border was amply protected. One of the steps taken was the enrollment and arming of the State militia. The Thirteenth Regiment, consisting of 500 men, was raised in Johnson County. Although arduous, the duties of the militia were cheerfully performed and produced a sense of security and protection that could not have been well otherwise obtained. As county citizens, they were protecting their own and their neighbors’ homes. This regiment distinguished itself in 1864, fighting General Sterling Price’s army when on its famous raid.

By Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated May 2024.

Also See:

William Quantrill – Renegade Leader of the Missouri Border War

Sources:

Blair, Ed; History of Johnson County, Stand Publishing Company, Lawrence, KS, 1915.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Deatherage, Charles P., Early History of Greater Kansas City, Interstate Publishing Co., 1927