Irving, Kansas, in Marshall County, lived a tragic life filled with drought, grasshoppers, and tornadoes before the Tuttle Lake Dam finally destroyed it.

In August 1859, ten citizens of Lyon City, Iowa, agreed to organize a town on government land in the West. Among them were three lawyers, two merchants, two doctors, a teacher, a preacher, and a hotel keeper.

W.W. Jerome was elected as their agent to go west and locate land for a new city. General Samuel C. Pomeroy, afterward a United States senator from Barrett, was at that time a land agent and personally conducted Mr. Jerome, in his conveyance, drawn by a team of mules, over the valleys of Blue and Kansas Rivers. Jerome finally decided to recommend Irving’s present site. In December 1859, ten founders left Lyons and proceeded by rail to St. Joseph, Missouri, and then by team to the new town’s location.

They named the town after author Washington Irving. The first house, measuring 19×24 feet, was built of hewn logs and used as a hotel. A frame building was next completed, and the lumber was hauled from Atchison.

In February 1860, the Territorial Legislature incorporated the Irving Town Company. But, in the spring of 1860, severe drought quickly ruined crops and forced some farmers to lose their land. Over the summer, the area was wracked with fierce winds and thunderstorms that blew down buildings, took roofs off, and damaged the sawmill. Though suffering, the town gained a post office in June 1860, with W.D. Abbott serving as the first postmaster. However, by fall, some residents chose to leave and return to Iowa or settle in other parts of Kansas. However, the majority remained and bravely pushed forward in building homes. Soon, others came in, and in 1861, the first church in Marshall County was completed.

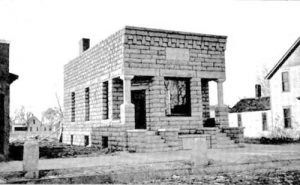

Doctor Parker influenced the establishment of the Wetmore Institute, built on a slope overlooking the town in 1861. The limestone building held a normal training school for young ladies, named after A. R. Wetmore of New York, who lent financial assistance for the building. Professor Charles Parker was in charge of the school, and the instructors were all highly educated and accomplished teachers. Despite the absence of young girls to receive instruction, the school was as well patronized as could be in a district so scant in population.

The survey of what was then known as the Atchison & Pike’s Peak Railroad was completed to Irving in November 1865. In 1866, grasshoppers invaded the community, destroying crops and trees.

Still, the community held tight, and in the fall of 1867, the Central Branch Union Pacific Railroad arrived. The railroad company refused to build a depot in Irving unless a deed to half the town was made to it. This was refused, and the railroad company located the depot one and a half miles southeast of the city. However, Senator Pomeroy exerted his influence and moved the depot to Irving. However, shortly after it was moved, it burned down. A second depot was built, and after lightning struck, it too burned down. A third depot was then erected.

The first schoolhouse, a stone building, was established in 1868. In 1870, a hotel, the Irving House, was erected.

Irving was incorporated as a city of the third class in 1871, and George C. Crowther was elected as the first mayor. However, the first city election was all that Irving ever held as a city, as the officers elected did not qualify; the charter was surrendered, and the “City of Irving” remained a village.

The town would have another grasshopper plague in 1875. Despite these hardships, in 1878, Irving was described as “being located in one of the best settled and best-cultivated portions of Marshall County.”

On May 30, 1879, two tornadoes destroyed most of the town, leaving 19 dead and many more injured. The storm approached the town from the west, and when it had passed beyond the limits of Irving, the village was left a mass of ruin, death, and desolation. This caused people to leave Irving, but buildings were rebuilt, and new businesses moved in, allowing Irving to regain its prominence as a local agricultural center. The first stone schoolhouse was destroyed by the cyclone and was replaced by a new frame building the same year.

In 1880, the Wetmore Institute, which had been damaged in the tornado of the year before, was destroyed by fire. It was never rebuilt, but to the people of Irving, it has the credit of having the first permanent church and the first institution for higher education in Marshall County.

In 1886, the Lincoln and Manhattan branch of the Union Pacific Railroad was completed, giving Irving a north and south railway.

During the summer of 1903, the Big Blue River flooded and destroyed homes, crops, and bridges. The river threatened to do it again in 1908, but the townspeople were prepared and could keep the river within its banks.

The Irving Telephone Company was organized in February 1904. Its lines operated west of Irving, and the Hawkinson Brothers Telephone Company, with lines east of Blue River, had a switch in Irving.

In 1910, Irving’s population was estimated at 403, and the town boasted good banking facilities, numerous stores, a weekly newspaper, telegraph and express offices, graded schools, a public library, and churches of all denominations.

However, with the close proximity of Blue Rapids, Irving’s population was falling. By 1916, its population was about 359. However, it still boasted several businesses in 1917. These included three general merchandise stores, a hotel, a barbershop, a hardware store, a garage, a bank, a lumber company, a grain elevator, a printing office, a shoe shop, a livery stable, a restaurant, a meat market, a grocery, an electric heater, and a photo studio. Services included two physicians, an undertaker, and several carpenters.

The Irving Telephone Company owned the system at Irving and Cleburn and connected with Blue Rapids, Frankfort, Bigelow and

Fostoria. The capital stock was $20,000, all of which were owned by members of the company, who were farmers.

In the following decades, the town’s population continued to decrease, but that would not be the death of the community. Instead, it was the building of Tuttle Creek Dam, ten miles to the south.

A stone marker commemorates the spot where the post office once stood in Irving, Kansas, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Beginning in the late 1930s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed a series of flood control projects in the Missouri River Basin. Congress authorized the Flood Control Act in 1944, which called for a series of large dams and levees on rivers in the basin. After the record-breaking floods of 1951, the Corps of Engineers proceeded with a plan to build a network of major reservoirs on rivers, including one to build the Tuttle Creek Dam.

After plans for the dam construction were announced, Irving’s population declined, and many businesses closed. The post office closed in 1960, and the townsite was abandoned the same year even though the lake was miles away.

Though Irving was abandoned, the townsite remains accessible, and its road network and building foundations are still visible. A stone marker sits in a makeshift park, along with a mailbox and notebook where visitors can write. It is located at Zenith and 12th Roads.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated November 2024.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Marshall County

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Forter, Emma Elizabeth Calderhead; History of Marshall County, Kansas: Its People, Industries, and Institutions; B.F. Bowen, 1917.

Wikipedia