Towns & Places:

Esbon

Jewell

Mankato (County Seat)

Randall

Webber

Extinct Towns of Jewell County

Jewell State Fishing Lake

Lake Emerson

Lovewell Reservoir & State Park

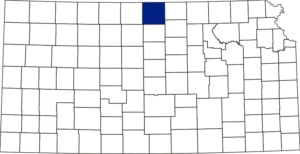

Jewell County, Kansas, is located in the north-central part of the state. Its county seat and most populous city is Mankato. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 2,932. Its total area was 914 square miles, of which 910 square miles were land and 4.6 square miles were water.

Located 150 miles from the Missouri River, the county was named in honor of Lewis R. Jewell, lieutenant colonel of the Sixth Kansas Cavalry, who died of wounds received in the Battle of Cane Hill, Arkansas, during the Civil War.

Lieutenant Zebulon Pike.

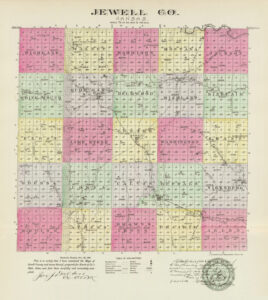

Jewell County is bounded on the north by the State of Nebraska, on the east by Republic and Cloud Counties, on the south by Mitchell County, and on the west by Smith County. Jewell was one of the counties on the line of the historic Pawnee Road and one of the counties crossed by Lieutenant Zebulon Pike in 1806. The rolling prairie surface gradually rises to table lands in the central portion. The branches of the Republican and Solomon Rivers form its water system.

The principal streams were White Rock, Buffalo, Limestone, Marsh, and Brown’s Creeks. White Rock Creek flowed east and emptied into the Republican River in Republic County. Its principal tributaries from the north were Burr Oak, Walnut, and Montana, and from the south were Porcupine, Troublesome, Big Timber, and John’s Creeks.

The soil was a rich, black vegetable mold, from one to 20 feet deep, underlaid principally with a porous clay. The valleys produced good crops with far less rain than the uplands and were more seriously affected by excessive rain. Good water was found at varying depths across the county, from level surfaces or springs to depths of 125 feet.

William Harshberger, his wife, and A. Clark made the earliest known settlement on White Rock Creek in 1862. Mrs. Clark and Mrs. Harshberger were sisters, and they all came from Knox County, Illinois. Soon, John Furrows took a claim just west of Mr. Harshberger’s farm. They formed the first settlement in Jewell County, built cabins, and broke ground. A battle between the Pawnee and Sioux was fought near Clark’s cabin, and one of the Pawnee Indians was hacked to pieces. On this occasion, these settlers were warned of a threatened outbreak and told that it boded no good for the whites of White Rock Valley. The Indians soon drove them out, and no other attempt was made to settle the county until the Spring of 1866.

At that time, William Belknap took a claim five miles west of the town of White Rock; John Marling, with his wife and child, settled near the present town of Reubens; Nicholas Ward, his wife and adopted son; Mrs. Sutzer and son, Al. Dart, Arch. Bump, Erastus Bartlett, and a man named Flint took claims within two miles east of that town. However, the area was still not safe. In August of this year, a party of 40 Cheyenne attacked Marling’s cabin, and while he was gone for assistance, they entered his house, dragged his wife into the woods with a rope around her neck, and outraged her. They then stole everything they could find, set fire to the cabin, and dashed off before Mr. Marling could obtain assistance from the stockade below White Rock City.

Afterward, the entire settlement took refuge there for two days, then went to Clyde in Cloud County. A few days afterward, learning that the rumors of a general massacre were groundless, the settlers returned to their claims. They rested in security until the following April, when a horrible event effectively destroyed the little settlement from the face of the earth.

Indian Attack by Charles Russell.

On April 30, 1867, the Cheyenne made another descent upon this settlement, killing Erastus Bartlett, Mariah Setzer, her young son, Jacob, and Nicholas Ward, and desperately wounding Ward’s adopted son, leaving him for dead and carrying Mrs. Ward off as a captive.

The Indians came to Mariah Setzer’s cabin, where Erastus Bartlett was boarding, and demanded dinner, which she prepared. In the meantime, she sent her young son, Jacob, across the creek to the Ward’s home to inform them of the Indians’ presence. Erastus Bartlett was down in the timber, splitting rails and returning for dinner, when he was met by the Indians and tomahawked as he passed around the corner of the house. He was found lying on his back, his iron wedge near his right hand and his own knife sticking in his throat. It is thought that when Bartlett was killed, Mrs. Setzer started to run. She was found dead about 30 yards from the house, with her skull crushed with a rock. The Indians had refrained from using firearms for fear of raising an alarm.

After completing their bloody work at Mrs. Setzer’s, the Indians crossed the creek to Ward’s cabin and again called for dinner, which Mrs. Ward prepared for them. They ate their dinner, smoked their pipes, and chatted in a friendly manner. After their “smoke,” one of them very coolly loaded his gun and asked Ward if he thought it would kill a buffalo. Nicholas Ward replied that he thought it would. After that, the Indian instantly leveled his gun at Ward’s breast and shot him through the heart, killing him immediately. The two boys – Ward’s and Mrs. Setzer’s – started running. The Indians pursued them, following them to the bank of the creek and shooting them down in the creek bed. The Setzer boy was shot through the heart and instantly killed. The Ward boy was shot through the neck and left for dead. Sometime during the succeeding night, however, he recovered his senses and, groping his way back to the cabin in the dark, found the door broken down and entered. Feeling around in the dark with his hands, he stumbled and fell over the dead body of his adopted father. Procuring some blankets from one of the beds, he returned to the timber, where he remained during the night, and was found the following day by a party of claim hunters, to whom he told the sad and harrowing tale. It appeared that when the Indians ran out to shoot the boys, Mary Ward must have shut and bolted the door when the Indians, returning, broke it down and took her prisoner.

Scouting parties who arrived a few days later trailed the raiders and their captive but were forced to call off the search after reaching the banks of the Solomon River about 40 miles away. Mary Ward probably died of exposure before the end of summer, but not before being spotted by a company of soldiers from Fort Riley who reported seeing a tall, haggard woman fitting her description, who ran away “in a crazy manner” at their approach.

Of the original members of the settlement who were not victims of this massacre, Mr. Flint was absent at Clyde, the Darts were absent, Mr. Marling, his wife, and child had returned to Missouri, and Mr. Bump and Mr. Davis had been waylaid and shot in Cloud County the previous May. The survivors, including Mr. Rice, all left the county after this terrible affair.

In the winter and spring of 1868, Richard Stanfield and Carl G. Smith took claims in Sections 7 and 9, Township 2 south, and Gordon Winbigler and Adam Rosenberg near White Rock Creek and Rubens. Mr. Rosenberg was with General George Custer in his famous expedition to the Indian Territory (Oklahoma), where Mrs. Morgan and Miss White were rescued from the Indians.

Indians broke up another attempt at settlement in the spring of 1868 and again in October of the same year. They also drove back the extension of a Scandinavian colony up White Rock Creek from Republic County.

In May 1869, the Excelsior Colony from New York, which consisted of about 100 people, took claims along White Rock Creek and built a blockhouse eight miles north of present-day Mankato.

In the latter part of May 1869, there were over 100 people in the county, all on White Rock Creek. During this month, a force of men was raised and proceeded to the scene of a late massacre in the northwestern part of Jewell County, in which four hunters from Nebraska had been killed. Prior to their return, John Dahl, one of the Scandinavian settlers, was killed by Indians, Peter Tanner’s cabin was burned, and other outrages were committed. The Excelsior Colony, consisting of Mrs. Frazier and her two sons, Mr. Walker, President of the company, and others, considered that they were “wanted elsewhere” than in this locality and made immediate preparations to depart. While a portion of them were moving their household effects from their fort to the protecting care of Mr. Lovewell and his band, they were attacked by Indians, robbed of all their possessions, but escaped alive. At the time, Mr. Walker was at Junction City, Kansas, and, hearing of the raid, sent up many men and some teams and, in June, moved away. All the Scandinavian settlers had already left, leaving Jewell County entirely deserted.

Jewell County remained desolate from June until August 1869, when Peter Kearns ventured in and took the old Nicholas Ward claim. He worked it the following winter. A.N. Cole homesteaded near the present town of Ionia that year.

Several settlements were made in 1870. William Friend, C.J. Jones, O.F. Johnson, M. Hofiveimer, Lewis Spiegle, and Silas Mann settled the Marsh Creek District. A.W. Mann, Zack Norman, Lee M. Tingley, Richard Comstock, Frank Gilbert, A.J. Godfrey, D.H. Godfrey, Allen Ives, John E. Faidley, and E.E. Blake settled at Burr Oak.

In early May 1870, great excitement prevailed over the news that the Cheyenne were on the warpath. On May 13, the settlers met at “Hoffer’s Shanty” to devise means of protection. A company of 28 men, known as the “Buffalo Militia,” was organized with William D. Street as captain; Charles Lew, first lieutenant; Louis A. Dapron, second lieutenant; James A. Scarborough, orderly sergeant. Fort Jewell was built where Jewell City now stands. It was held by the “Buffalo Militia” for about a month, after which the Third U.S. Mounted Artillery took possession and relieved the settlers. No more attacks were made, and afterward, Jewell County was free from hostile Indians.

The first regular mail was established in July 1870, weekly from Sibley in Cloud County, with John Hoffer as the carrier.

That month, Colonel E. Barker and Orville McClurg petitioned Governor James Harvey for the organization of the county. On July 14, the governor appointed C.L. Seeley, E.T. Gandy, A.I. Davis, county commissioners, and James A. Scarborough, county clerk. The commissioners’ first meeting was held at Jewell City on August 22. On September 27, an election was held, at which Jewell City was chosen the county seat over a paper town called “Springdale,” and the following county officers were elected: Dennis Taylor, Thomas Coverdale, and Samuel C. Bowles, commissioners; James A. Scarborough, clerk; Henry Sorick, treasurer; N.H. Billings, surveyor; S.O. Carman, register of deeds; Charles L. Sully, probate judge; A.J. Davis, sheriff; R.S. Worick, county superintendent. Felix T. Candy was elected the first representative in the legislature in November. The county’s population at that time was 207.

In 1871, H.M. George and H.L. Browning started a steam sawmill on the freight road between Cawker City and Hastings, Nebraska, where Salem would later be established.

That year, Guy Whitmore and Jake Hanes, noted horse thieves, were arrested by William Stone, the Jewell County Sheriff at Grand Island, Nebraska. When taken, they had eleven stolen horses in their possession. When the Sheriff reached his home near Salem, he remained overnight with the prisoners. Leaving them with his Deputy, he went out on an errand, and during his absence, a mob overpowered the deputy and hung the prisoners to a tree. Efforts were made to discover the perpetrators, but without success. The Sheriff never received his pay for the capture, as the County Commissioners claimed that he did not “produce the prisoners dead or alive.”

The first post offices were in Johnsonville, in Vicksburg Township, in 1871, with P.F. Johnson as postmaster; Amity in Highland Township, in 1872, with James Mitchell, postmaster; Burr Oak, Burr Oak Township, with James McCormack, postmaster; Jewell Center, Center Township, in 1872, with J.D. Vance as postmaster.

In 1872, schools were established in several townships, and that year Jewell Center (Mankato) was established.

By 1873, other towns had been established, including Burr Oak, Salem, Ionia, and Holmwood, and the county had six newspapers.

In the meantime, Jewell Center had grown so much that the townspeople petitioned for an election to move the county seat from Jewell City to Jewell Center. The election was held on May 13, 1873, and the county seat was moved to Jewell Center by a majority vote of 235.

The county buildings of Mankato were small, inconvenient, and unsafe for keeping the records of such a large county. The courthouse was a small frame building donated by the citizens of Mankato to secure the county seat. A courthouse square was set apart in the most elevated portion of the town, where it was intended to erect a courthouse commensurate in size and elegance with the county’s importance. The county poor farm, which occupied 200 acres, was located one mile south of Mankato. The poorhouse building cost about $4,000.

Jewell City relocated the county seat to its town in 1875, prompting another election on June 28, 1875. The result was a majority vote of 206 in favor of moving the county seat back to Jewell Center. This was the last election held at the county seat.

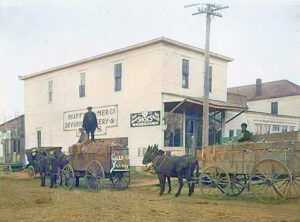

In 1877, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad built a branch line from Neva, Kansas, three miles west of Strong City, to Superior, Nebraska. This branch line connected Strong City, Neva, Rockland, Diamond Springs, Burdick, Lost Springs, Jacobs, Hope, Navarre, Enterprise, Abilene, Talmage, Manchester, Longford, Oak Hill, Miltonvale, Aurora, Huscher, Concordia, Kackley, Courtland, Webber, Superior. This branch line was initially called the “Strong City and Superior Railroad,” but later, the name was shortened to the “Strong City Railroad.”

Students in Jewell County, Kansas, about 1890.

That year, there were 133 organized school districts, 60 schoolhouses in total, $21,412 in school property, and 4,561 students.

The main line of the Central Branch of the Missouri Pacific Railroad, built by the Union Pacific Railroad, was built in 1878 and 1879. It extended along the southern boundary of the county, a branch of which ran up the Buffalo Valley to Burr Oak on White Rock Creek.

In 1881, the Jewell Center’s name was changed to Mankato because it resembled that of its rival, Jewell City.

By the early 1880s, Jewell County was among the first in the state in terms of agricultural resources. Its central portion was rolling and, in places, somewhat broken, but contained many fine farms and much good pasture land. The valley of Marsh and Buffalo Creeks – a tract embracing the southeast quarter of the county next to the White Rock Valley was the county’s most prosperous and most densely settled portion. It was about 50 to 75 feet below the central portion and was exceedingly fertile, just rolling enough to afford proper drainage.

In every township except Highland, magnesian limestone was the principal building stone. When first quarried, it was generally soft and easily cut with a standard saw, but it became hard with exposure. Sandstone was found in the extreme south.

By 1886, Randall, Omia, Gregory, and Rubens had been added to the list of towns.

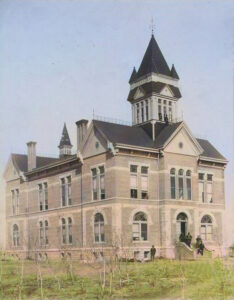

Second Jewell County Courthouse in Mankato, Kansas, early 1900s.

In 1887, the second Jewell County Courthouse in Mankato was built in the city’s public square. The two-story brick building featured a pitched roof with rectangular and arched windows, and its interior consisted of 13 rooms. The building stone was quarried from the H.P. Diamond farm in Richland Township. The structure served as the county courthouse until November 1937, when a new courthouse was dedicated.

Jewell County’s population peaked in 1900 at 19,420. Afterward, its population has steadily declined every decade.

In 1910, the school population was 18,148, and the assessed property valuation was $38,625,285.

In 1936-1937, the third and present courthouse was constructed at 307 North Commercial Street in Mankato.

The three-story buff-colored limestone-and-concrete structure, designed in the Art Deco style, was built by the Works Progress Administration for $159,891. It is located on landscaped grounds in the center of Mankato. The original wooden doors, with ornate white metal push bars and glazed transoms, are intact in the interior. Each floor has a north-south-running corridor and is accessed by the primary staircase on the east side of the building and a secondary enclosed staircase at the northwest corner. Interior finishes include vinyl floor tile, glazed block wainscoting, plastered walls and ceilings, and oak doors and trim.

In 1982, the north wing of the courthouse was constructed to house the jail.

In 1996, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad, forming the current BNSF Railway.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated December 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

American Courthouses

Blackmar, William; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Standard Publishing Co., Chicago, IL,1912.

Cutler, William; History of the State of Kansas, A.T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Fort Hays State University

Kansas Press Association

Wikipedia