Newton, Kansas, the county seat of Harvey County, was founded when the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad extended a main line from Emporia westward. The town was named after Newton, Massachusetts, home of some of the Santa Fe Railroad stockholders.

The first frame building on the townsite was moved from Darlington Township in March 1870 and used as a blacksmith shop by two men named Stockwell and Walton. Peter Luhn erected the next building, the Pioneer Store, and David and Steele erected a third building, which they opened as a bakery. By May 1871, new buildings were going up daily as the town’s future was assured. The post office opened on June 6, 1871, with W. A. Russell as the first postmaster.

In July 1871, the railroad reached Newton, and the town immediately became an important shipping point for immense herds of Texas longhorns driven north on the Chisholm Trail.

Before this time, the cattle had been driven to Abilene, Kansas. Many people began to settle in the area in anticipation of the railroad’s arrival, including cowboys, saloon men, gamblers, soiled doves, and roughs of every nationality and color. In harmony with their surroundings and character, most were armed and lived in a part of the city known as “Hyde Park.” Here, at least 15 buildings were erected and devoted to “social amusement,” which these characters figured conspicuously. Nearly every other building in the business portion was occupied by saloons, with names like “Do Drop-In,” “The Side Track,” “Gold Rooms,” and other names that were suggestive of the times. In total, the town boasted 27 saloons and eight gambling halls. During these days, Newton was filled with tales rivaled only by Dodge City and was called the “wickedest city in the west.”

During this rowdy year as a Kansas cowtown, about 600,000 head of cattle were driven up the trail, and Newton became extremely rowdy. The popular gathering spot was Hyde Park, located south of the railroad tracks and west of Main Street. This area contained the largest saloons and the red-light district. It was so named because the “girls showed so much of their hide.” As the fledgling town did not yet have an official police force, violence and shootings were common in the summer of 1871, during which time several people were wounded, and about 12 were killed in shooting scrapes.

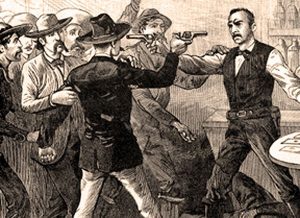

The most notorious was the Newton Massacre, also called the Hyde Park Gunfight.

“The entire country east, west, and south of Salina and down to the Arkansas River is filled with Texas cattle… The bottoms are overflowing with them, and the watercourses with this great article of traffic… And the cry is, “still they come!”

— Saline County Journal, July 20, 1871

The Hyde Park Gunfight occurred at Perry Tuttle’s Dance Hall on August 20, 1871. The affair began when Billy Bailey and Mike McCluskie argued over local politics on August 11 in the Red Front Saloon. Both men had been hired by Newton authorities as Special Policemen to keep order in the city during the heated August elections. The argument turned into a fistfight that ended with two shots fired at Bailey, who died the next day.

McCluskie fled town but had returned to Newton by the following Saturday (August 19). That evening, McCluskie was in Perry Tuttle’s Dance Hall on West Second Street in Hyde Park. Sometime after midnight on Sunday, August 20, three of Bailey’s Texas cowboy friends entered the dance hall. Soon, another Texas cowboy named Hugh Anderson, the son of a wealthy Bell County, Texas cattle rancher, also entered the dancehall, walking directly up to McCluskie and yelling, “You are a cowardly son-of-a-bitch! I will blow the top of your head off!”

Though a man named Jim Martin jumped up and attempted to stop any violence, Anderson ignored him and shot McCluskie in the neck. McCluskie, though down, returned the fire after he was down, wounding Anderson. Anderson then pumped several more shots into McCluskie, killing him. The other Texas cowboys also began firing, and all hell broke loose. The gunfight resulted in the death of five of its participants and the wounding of as many more.

The Hyde Park area today is a residential neighborhood with no traces of its troubled past. There are no historical markers or preserved structures from the summer of 1871. It was located in the 200 block of West Second, and the former Tuttle’s Dance Hall site is now a parking lot.

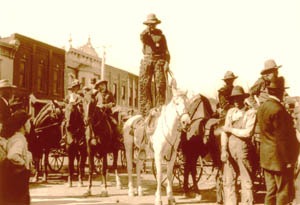

Newton, Kansas, 1872.

Violence continued through the fall in Newton, but by 1872, the town’s climate had begun to change. By that spring, the trailhead had moved south to Wichita, and many of the businesses catering to cowboys followed. Newton was incorporated in February 1872. In April, James Gregory was elected mayor. Soon, the city council passed an ordinance prohibiting the running of large animals through the city. By that time, a depot had been constructed.

On August 10, 1872, residents voted to issue $5,000 in bonds to erect a brick schoolhouse. Miss Mary Boyd opened the first public school on August 26, 1872.

Newton Kansan Newspaper.

The Newton Kansan, the town’s first newspaper, was first published on August 22, 1872, under the editorship of H.C. Ashbaugh. It was the first newspaper published in Harvey County and continues to be published today.

The new brick schoolhouse was opened to students in 1873. Unfortunately, on the evening of December 8, 1873, a disastrous fire destroyed one of the city’s best business districts.

In April 1875, the city’s population was 769, a significant decrease from the returns of 1872. However, during the spring and summer of 1875, the town sprang into and entered a new life, and in 1878, it boasted a population of over 2000.

In 1880, partners Judge R.W.P. Muse and R.M. Spivey presented plans for a new hotel and depot. The Hotel de Strong officially opened in the fall of 1881. Estimated to have cost about $75,000, the three-story stone building with a brick veneer was named after William B. Strong, the new president of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

By 1881, Newton was a thriving little city of the second class, with handsome brick blocks, fine residences, churches, schools, and newspapers. By that time, Newton had grown to about 5,000 people.

In May 1882, the Hotel de Strong was renamed the Arcade Hotel, and Fred Harvey leased space to run one of his many restaurants along the Santa Fe line.

On May 11, 1887, Newton representatives met with the Kansas Conference of Mennonites to sign a charter for Bethel College to be built on about 120 acres. In October 1888, the cornerstone of the Administration Building was laid. It would be five years before the building was completed. In September 1893, classes began with 74 students.

In the subsequent decades, more classroom buildings and residence halls would be added to the campus. Today, Bethel College is a private Christian liberal arts college that is still affiliated with the Mennonite Church. The Richardsonian Romanesque administration building is on the National Register of Historic Places. The school is located in North Newton, Kansas.

In 1898, the Santa Fe Railroad purchased the Arcade Hotel and remodeled it inside and out for about $52,000.

“The mansard roof, the distinguishing characteristic of the old structure, is now no more, the wall of the third story being of solid brick… The dining room and lunch counter were located on the south side of the first floor, with easy access from the trains. The office is on the Main Street side of the house. It is a large and airy room, and attracts the guests at once with its quiet elegance. The chairs are of an old-fashioned pattern but finely upholstered in leather. The ceiling is formed of pressed steel squares, giving it a fine fresco effect.”

— Kansan-Republican, May 15, 1900

In 1906, the first Harvey County Courthouse was built in Newton. The three-story red brick structure was built in a modified Romanesque Revival style dominated by a tall clock tower. Bedford stone highlighted the exterior, with marble lining the interior hallways. Built at $47,701, each office had a fireplace, natural gas, electricity, and a telephone. P.J. Galle presided over the first court session on November 6, 1907. Unfortunately, the magnificent building was razed in 1966, and a new courthouse was built on the same site.

By 1910, Newton was a division point of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad and a station for the Missouri Pacific and St. Louis-San Francisco Railroads.

The abundance of natural gas in the area made Newton a manufacturing town. It also had a grain drill factory, an alfalfa mill, wagon works, a threshing machine factory, cornice works, and several small plants devoted to various productions. It also boasted a building and loan association, a creamery, three flour mills, three large elevators, and several well-appointed stores.

In addition to excellent public schools, Newton had two colleges, Bethel College (Mennonite) and the Evangelical Lutheran (Congregational). Its business interests included four banks, a daily newspaper called the Evening Journal, three weekly newspapers, and a German newspaper called the Volksblatt.

Two parks, a hospital, local and long-distance service, a Carnegie library, 24 daily passenger trains, waterworks, an efficient sewer system, an electric light plant, an ice plant, 17 churches, and a government building were among the metropolitan conveniences. At that time, the city had a population of 7,862.

After serving Newton for nearly 31 years, the Arcade Hotel was demolished, and the depot was rebuilt. Despite the Great Depression, the new Jacobean-style building was constructed between 1929 and 1930 at a cost of $350,000. The two-story brick building included a passenger depot, Harvey House Restaurant, and dorms for the Harvey girls on the second floor. Fred Harvey was known for his strict dining standards, serving methods, and excellent dining experience along the Santa Fe line. The Harvey House Restaurant would continue to operate until May 1957. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the old depot operates as an Amtrak stop, and businesses occupy the rest of the building.

During World War II, the US Navy took over Newton’s airport as a secondary Naval Air Station, and the main runway was extended to over 7,000 feet.

Newton continued to serve as the Middle Division dispatching headquarters for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad until the mid-1980s, when all dispatching for the Chicago to Los Angeles system was centralized in the Chicago area. In 1995, the Santa Fe merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad. Today, the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway remains a large industrial taxpayer, although its impact has decreased in recent years.

Today, Newton continues to flourish with several historic buildings and an estimated population of about 19,000.

Newton is located 25 miles north of Wichita and 33 miles east of Hutchinson.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated June 2025.

More Information:

Newton Convention & Visitors Bureau

201 E. Sixth St.

Newton, Kansas

316-284-3642

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Newton Driving Tour

Wikipedia