Kansas Frontier.

In 1850, the long line separating the Indian and agricultural frontiers was just a little farther west than the point that it had reached by 1820. Then, it arrived at the bend of the Missouri River, where it remained for 30 years. Its flanks had swung out during this generation, including Arkansas to the south and Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin to the north. At the close of the Mexican-American War, the line was nearly a true meridian crossing the Missouri River at its bend. West of this spot, it had been kept from going by the tradition of the desert and the pressure of the Indian tribes. The country behind had filled up with population, and Oregon and California had appeared across the desert, but the barrier had not been pushed away.

Accurate knowledge of the Far West began to come through the great trails that penetrated the desert. By 1850, the tradition that Zebulon Pike and Stephen Long had helped to found had well-nigh disappeared, and covetous eyes had been cast upon the Indian lands across the border—lands from which the tribes were never to be removed without their consent and which were never to be included in any organized territory or state. Most of the traffic over the trails and through this country had defied treaty obligations. Some of the tribes had granted transit rights, but the privileges needed and used by the Oregon, California, and Utah hordes were far more than these. Most of the emigrants were technically trespassers upon Indian lands as well as violators of treaty provisions. Trouble with the Indians had begun early in the migrations.

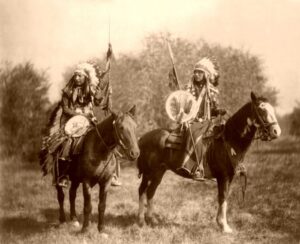

At the very beginning of the Oregon movement, the Indian office had foreseen trouble: “Frequent difficulties have occurred during the spring of the last and present year [1845] from the passing of emigrants for Oregon at various points into the Indian Country. Large companies have frequently rendezvoused on the Indian lands for months before the period of their start. The emigrants had two advantages in crossing into the Indian Country at an early period of the spring: one, the facility of grazing their stock on the rushes with which the lands abound, and the other, that they cross the Missouri River at their leisure. In one instance, the military forced a large party to push back. This passing of the emigrants through the Indian Country without their permission could result in an unpleasant collision, if not bloodshed. The Indians said that the whites had no right to be in their country without their consent, and the upper tribes, who subsisted on game, complained that the buffalo were wantonly killed and scared off, which rendered their only means of subsistence more precarious every year. John C. Fremont had seen, in 1842, that this invasion of the Indian Country could not be kept up safely without a show of military force and had recommended a post at the point where Fort Laramie, Wyoming, was finally established.

The years of the great migrations steadily aggravated the relations with the Indian tribes, while the Indian agents continually called upon Congress to redress or stop the wrongs being done, as often by panic-stricken emigrants as by vicious ones. “By alternate persuasion and force,” wrote the Commissioner in 1854, “some of these tribes have been removed, step by step, from mountain to valley, and from river to plain, until they have been pushed halfway across the continent. They can go no further; on the ground they now occupy, the crisis must be met and their future determined… There they are, and as they are, with outstanding obligations on behalf of the most solemn and imperative character, voluntarily assumed by the government.” However, the relentless westward movement had no regard for the rights of Mexico in either Texas or California, and could not be expected to notice the rights of Indians. It demanded that its own citizens’ rights not be inferior to those conceded by the government “to wandering nations of savages.” A shrewd and experienced Indian agent, Thomas Fitzpatrick, who had the confidence of both races, voiced this demand in 1853. “But one course remains,” he wrote, “which promises any permanent relief to them or any lasting benefit to the country in which they dwell. That is to make such modifications in the ‘intercourse laws’ as to invite the traders’ residence amongst them and open the whole Indian territory to settlement. In this manner will be introduced amongst them those who will set the example of developing the resources of the soil, of which the Indians have not now the most general idea; who will afford to their employment in pursuits congenial to their nature; and who will accustom them, imperceptibly, to those modes of life which can alone secure them from the miseries of penury. Trade is the only civilizer of the Indians. It has been the precursor of all civilization heretofore, and it will be of all hereafter… The present ‘intercourse laws’ too, so far as they are calculated to protect the Indians from the evils of civilized life—from the sale of ardent spirits and the prostitution of morals—are nothing more than a dead letter, while, so far as they contribute to excluding the benefits of civilization from amongst them, they can be, and are, strictly enforced.”

In 1849, Congress transferred the Indian Office from the War Department to the Interior, with the idea that the Indians would be better off under civilian rather than military control. Shortly after this, negotiations began to explore new settlements with the tribes. The Sioux were persuaded in the summer of 1851 to make way for an increasing population in Minnesota, while in the autumn of the same year, the tribes of the western plains were induced to make concessions.

The significant treaties signed at the Upper Platte agency at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, in 1851, were in the interest of the migrating thousands. Fitzpatrick had spent the summer of 1850 summoning the bands of Cheyenne and Arapaho to the conference. The Shoshone were brought in from the West. The Sioux, Assiniboine, Arikara, Gros Ventre, and Crow came from the north of the Platte River. The treaties here concluded were never ratified in full, but for 15 years, Congress paid various annuities provided by them, and in general, the tribes adhered to them. The right of the United States to make roads across the plains and to fortify them with military posts was fully agreed to, while the Indians pledged themselves to commit no depredations upon emigrants. Two years later, at Fort Atkinson, Fitzpatrick had a conference with the Plains Indians of the south, Comanche and Apache, making “a renewal of faith, which the Indians did not have in the Government, nor the Government in them.”

Overland traffic was made safer for several years by these treaties. Such friction and fighting, as occurred in the 1850s, were due chiefly to the emigrants’ excesses and fears. However, in these treaties, there was nothing for the eastern tribes along the Iowa and Missouri border, who were in constant danger of dispossession by the advance of the frontier itself.

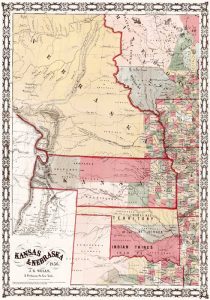

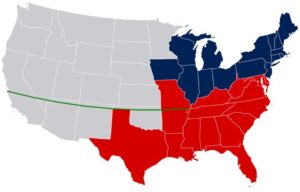

Missouri Compromise Map.

The settlement of Kansas, becoming probable in the early 1850s, was the impending danger threatening the peace of the border. There was no special need to extend colonization across Missouri since Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, and Minnesota were sparsely inhabited. Settlers might be accommodated farther to the east for years. However, the slavery debate of 1850 had revealed and aroused passions in both the North and South. Motives were so thoroughly mixed that participants were rarely able to give satisfactory accounts of themselves. Love of struggle, desire for revenge, and political ambition all mingled with pure philanthropy and a reasonable fear of outside interference with domestic institutions. The compromise had settled the future of the new lands. Still, the residue of the Louisiana Purchase lay between Missouri and the mountains, divided truly by the Missouri Compromise line but not yet settled. Ambition to possess it, to convert it to slavery, or to retain it for freedom was stimulated by the debate and the fears of outside interference. The nearest part of the unorganized West was adjacent to Missouri. Hence, Kansas came first in the public vision.

It is possible to trace a movement for territorial organization in the Indian Country back to 1850 or even earlier. Certain of the more intelligent of the Indian colonists had been able to read the signs of the times, with the result that organized effort for the territory of Nebraska had emanated from the Wyandot country and had besieged Congress between 1851 and 1853. The obstacles on the road to fulfillment were the Indians and the laws. Experience had long demonstrated the unwisdom of permitting Indians and emigrants to live in the same districts. The removal and intercourse acts, and the treaties based upon them, had guaranteed in particular that no territory or state should ever be organized in this country. Good faith and the physical presence of the tribes had to be overcome before a new territory could appear.

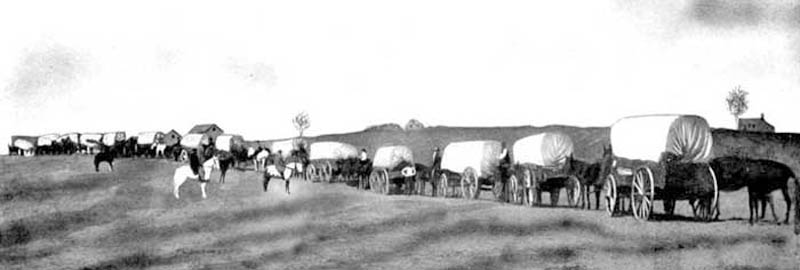

Overland Emigrant and Freight Train, Operated by Sprague & Digan in Kansas, April 1, 1866, en route to the Far West.

The guarantee of permanency was based upon a treaty and, in the eyes of Congress, was not so sacred that it could not be modified by treaty. As it became clear that the demand for the opening of these lands would soon have to be granted, Congress prepared for the inevitable by ordering, in March 1853, a series of negotiations with the tribes west of the Missouri River with a view to the cession of more country. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, George W. Manypenny, who later wrote a book on “Our Indian Wards,” spent the subsequent summer breaking to the Indians the hard news that they were expected once more to vacate. He found the tribes uneasy and sullen. Occasional prospectors, wandering over their lands, had set them thinking. There had been no actual white settlement until October 1853, so Manypenny declared, but the chiefs feared that he was contemplating a seizure of their lands. The Indian mind had difficulty comprehending the difference between ceding their land by treaty and losing it by force.

At a long series of council fires, the Commissioner soothed away some of the apprehensions but found a stubborn resistance when discussing ceding all the reserves and moving to new homes. The tribes, under pressure, were ready to part with some of their lands but wanted to retain enough to live on. When he talked to them of the Great Father in Washington, Manypenny himself felt the irony of the situation; the guarantee of permanency had been explicit and straightforward. Yet he arranged for a series of treaties in the following year.

In the spring of 1854, treaties were concluded with most of the tribes on the Missouri River. Some of these had been persuaded to move into the Missouri Valley in the negotiations of the 1830s. Others, always resident there, had accepted curtailed reserves. The Omaha faced the Missouri River, north of the Platte River. South of the Platte River were the Otoe and Missouri, the Sac and Fox of Missouri, the Ioway, and the Kickapoo. The Delaware Reserve, north of Kansas and around Fort Leavenworth, was the seat of an Indian civilization of a high order. The Shawnee, immediately south of the Kansas River, were also well advanced in agriculture in the permanent home they had accepted. The confederated Kaskaskia, Peoria, Wea, Piankashaw, and Miami were further south. More than 13 million acres of land were bought in the treaties of 1854 from those tribes. In scattered and reduced reserves, the Indians retained about one-tenth of what they ceded for themselves. Generally, when the final signing came, under the persuasion of the Indian Office, and often amid the strange surroundings of Washington, the chiefs surrendered the lands outright and with no condition.

Certain of the tribes resisted all importunities to give title at once and held out for conditions of sale. The Iowa, the confederated minor tribes, and notably the Delaware, ceded their lands in trust to the United States, with the treaty pledge that the lands so yielded should be sold at public auction to the highest bidder, the remainders should then be offered privately for three years at $1.25 per acre, and the United States should dispose of the final remnants, the accruing funds being held in trust by the United States for the Indians. By the end of May, nearly all of the treaties had been concluded. In July 1854, Congress provided a land office for the territory of Kansas.

While the Indian negotiations were in progress, Senator Stephen Douglas forced his Kansas-Nebraska Act through in Washington, D.C. The bill had failed in 1853, partly because the Senate had felt the sanctity of the Indian agreement, but in 1854, the leader of the Democratic Party carried it along relentlessly. With words of highest patriotism upon his lips, as Rhodes has told it, he secured the passage of a bill not needed by the westward movement, subversive of the national pledge, and, blind as he was, destructive as well of his party and his political future. President Pierce’s support and Jefferson Davis’s cooperation were crucial to his success in the struggle. It was not his intent, he declared, to legislate slavery into or out of the territories; he proposed to leave that to the people themselves. To this principle, he gave the name of “popular sovereignty, and the name was a far greater invention than the doctrine.” With rising opposition all around him, he repealed the Missouri Compromise, which in 1820 divided the Indian Country by the line of 36° 30′ into free and slave areas. He created within these limits the new territories of Kansas and Nebraska. The President signed his bill on May 30, 1854. In later years, this day has been observed as a memorial to those who lost their lives in fighting the battle that he provoked.

With public sentiment excited and the Missouri Compromise repealed, eager partisans prepared in the spring of 1854 to colonize the new territories in the interests of slavery and freedom. On the slavery side, Senator David Atchison of Missouri was to be reckoned as one of the leaders. Young men of the South were urged to move, with their slaves and their possessions, into the new territories and thus secure these for their cherished institution. If votes should fail them in the future, the Missouri border was not far removed, and colonization of voters might be counted upon. Missouri, directly adjacent to Kansas and a slave state, naturally took the lead in this matter of preventing the erection of a Free State on her western boundary. The northern states had been stirred by the act as profoundly as the South. The bill was not yet passed in New England when abolition movement leaders prepared to act under it. During the spring, Eli Thayer of Worcester, Massachusetts, urged that friends of freedom could do no better work than aid in colonizing Kansas. In April, he secured a charter for a Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Society from his state, through which he proposed to aid suitable men to move into the debatable land. Churches and schools were to be provided for them. A stern New England abolition spirit was to be fostered by them. And they were not to be left without the usual border means of defense. A wealthy philanthropist, Amos A. Lawrence of Boston, made Thayer’s scheme financially possible. Dr. Charles Robinson was their choice for the leader of emigration and local representative in Kansas.

The resulting settlement of Kansas was stimulated little by the ordinary westward impulse but greatly by political ambition and sectional rivalry. As late as October 1853, there were almost no whites in the Indian Country. Early in 1854, they began to come in, in increasing numbers. The Emigrant Aid Society sent its parties before the ink was dry on the treaties of cession and before land offices had been opened. The Missouri River steamers approached Kansas City and Westport, Missouri, near the river’s bend, which was the gateway into Kansas. The Delaware cession, north of the Kansas River, was not yet open to legal occupation, but the Shawnee lands had been ceded completely and would soon be ready. So, the New England companies worked their way on foot or in hired wagons up the right bank of the Kansas River, hunting for eligible sites. They picked their spot late in July, about 30 miles west of the Missouri line and the old Shawnee Mission. The town of Lawrence, Kansas, grew out of its cluster of tents and cabins.

It was more than two months after the arrival of the squatters at Lawrence before the new territory’s first governor, Andrew H. Reeder, appeared at Fort Leavenworth and established civil government in Kansas. One of his first experiences was with the attempt of United States officers at the post to secure for themselves pieces of the Delaware lands that surrounded it. “While lying at the fort,” wrote a surveyor who left early in September to run the Nebraska boundary line, “we heard a great deal about those d—d squatters who were trying to steal the Leavenworth site.” None of the Delaware lands were open to settlement since the United States had pledged itself to sell them all at public auction for the Indians’ benefit. But certain speculators, including regular army officers, organized a town company to preempt a site near the fort, where they thought they foresaw the great city of the West. They relied on the immunity that usually saved pilferers on the Indian lands and seemed even to have used United States soldiers to build their shanties. They had begun to dispose of their building lots “in this discreditable business” four weeks before the first Delaware trust lands were sold.

However bitter toward each other, the settlers agreed in their attitude toward the Indians and squatted regardless of Indian rights or United States laws. Governor Reeder himself convened his legislature, first at Pawnee, when troops from Fort Riley ejected it, then at the Shawnee Mission, close to Kansas City, where its presence was without the authority of law. He established election precincts in unceded lands and voting places at spots where no white man could go without violating the law. The legal snarl into which the settlers plunged reveals the inconsistencies in the Indian policy. It is even intimated that Governor Reeder was interested in a land scheme at Pawnee similar to that at Fort Leavenworth.

The fight for Kansas began immediately after Governor Reeder and the earliest immigrants arrived. The settlers in residence at the commencement of 1855 were about 8,500. Proximity initially gave Missouri an advantage when the North was not fully aroused. At an election for territorial legislature held on March 30, 1855, the threat of Senator Atchison was revealed in full when more than 6,000 votes were counted among a population of under 3,000 qualified voters. Missouri men had ridden over in organized bands to colonize the precincts and carry the election. The whole settlement area was within an easy two-day ride of the Missouri border. The fraud was so crude that Governor Reeder disavowed some of the results. However, the resulting legislature, meeting in July 1855, expelled some of its anti-slavery members while the rest resigned. It adopted the Missouri code of law, thus laying the foundations for a slave state.

The political struggle over Kansas became more intense on the border and more absorbing in the nation in the next four years. As the settlers around Lawrence came to be known, the free-state men disavowed the first legislature because of its fraudulent election. At the same time, President Franklin Pierce steadily supported it from Washington, D.C. Governor Reeder was removed during its session, seemingly because he had cast doubt on its validity. Protesting against it, the northerners held a series of meetings in the autumn, around Lawrence and Topeka, some 25 miles further up the Kansas River, and crystallized their opposition under Dr. Robinson. Their efforts culminated at Topeka in October in a spontaneous, but in this instance revolutionary, convention that framed a free-state constitution for Kansas and provided for erecting a rival administration. Dr. Charles Robinson became its governor.

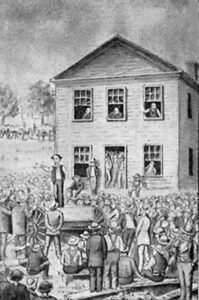

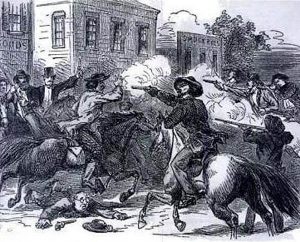

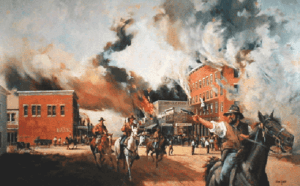

Before the first legislature under the Topeka Constitution assembled, Kansas had still further trouble. Private violence and mob attacks began during the fall of 1855. What is known as the Wakarusa War occurred in November, when Sheriff Samuel J. Jones of Douglas County tried to arrest some free-state men at Lecompton and met with strong resistance reënforced with Sharpe rifles from New England. Governor Wilson Shannon, who had succeeded Reeder, patched up peace, but hostility continued through the winter. Lawrence was increasingly the center of northern settlement and the object of pro-slave aggression. A Missouri mob visited it on May 21, 1856, and in the approving presence, it is said, of Sheriff Jones, sacked its hotel and printing shop and burned the residence of Dr. Robinson.

In the fall, a free-state crowd marched up the river and attacked Lecompton, but within a week of the Sacking of Lawrence, retribution was visited upon the pro-slave settlers. In cold blood, five men were murdered at a settlement on Potawatomi Creek by a group of fanatical free-state men. However, the provocation abolitionist John Brown and his family received, which may have excused his revenge, is not certain. In many instances, individual anti-slavery men retaliated lawlessly upon their enemies. However, the leaders of the Lawrence party have also led to censuring Brown and disclaiming responsibility for his acts. It is certain that in this struggle, the free-state party, in general, wanted a peaceful settlement of the country and were staking their fortunes and families upon it. They were ready for defense, but criminal aggression was no part of their platform.

The course of Governor Shannon reached its end in the summer of 1856. The free-state faction disliked him because his habits did not align with the pro-slavery cause. At the end of his regime, the extra-legal legislature under the Topeka constitution was prevented by federal troops from convening in session at Topeka. A few weeks later, Governor John W. Geary superseded him and established his seat of government in Lecompton, which was, by this time, a village of some twenty houses. It took Geary, an honest, well-meaning man, only six weeks to fall out with the pro-slave element and the federal land officers. He resigned in March 1857.

Under Governor Robert J. Walker, who followed Geary, the first official attempt at a constitution was entered upon. The legislature had already summoned a convention that sat at Lecompton in September and October. Its constitution, which was essentially pro-slavery, was ratified before the end of the year and submitted to Congress. Meanwhile, the legislature that called the convention had fallen into free-state hands, disavowed the constitution, and summoned another convention. At Leavenworth, this convention framed a free-state constitution in March, which was ratified by popular vote in May 1858. Governor Walker had already resigned in December 1857. By holding an honest election and purging the returns of slave-state frauds, he enabled the free-state party to secure the legislature. Southerner though he was, he choked at the political dishonesty of the administration in Kansas. He had yielded to the evidence of his eyes that the population of Kansas possessed a large free-state majority. But so yielding, he had lost the confidence of Washington. Even Senator Douglas, the patron of the popular sovereignty doctrine, had now broken with President James Buchanan, recognizing the right of the people to form their institutions. Congress has never paid any attention to this Leavenworth constitution. Still, when the Lecompton constitution was finally submitted to the people by Congress in August 1858, it was defeated by more than 11,000 votes in a total of 13,000. Kansas was henceforth in the hands of the actual settlers. A year later, at Wyandotte, it made a fourth constitution, under which it at last entered the union on January 29, 1861. “In the Wyandotte Convention,” says one of the local historians, “there were a few Democrats and one or two cranks, and probably both were of some use in their way.”

There had been no white population in Kansas in 1853 and no special desire to create one. However, the political struggle had advertised the territory on a large scale while the whole West was under the influence of the agricultural boom that was extending settlement into Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa. Governor Reeder’s census in 1855 found that about 8,500 had come in since the erection of the territory. The rioting and fighting, the rumors of Sharpe rifles, and the stories of Lawrence and Potawatomi, instead of frightening settlers away, drew them there in increasing numbers. A few came from the South, but the northern majority was overwhelming before the panic of 1857 laid its heavy hand upon expansion. There was a white population of 106,390 in 1860.

Under its normal influences, the westward movement extended the range of prosperous agricultural settlements into the Northwest. It had cooperated in the extension into that part of the old desert now known as Kansas. Chiefly, politics and, secondly, the call of the West were the order of causes that must explain the first westward advance of the agricultural frontier since 1820. Even in 1860, the population of Kansas was almost exclusively within a three-day journey of the bend in the Missouri River.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated August 2025.

Source: Paxson, Frederic L.; Last American Frontier, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1910. Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War