The Severe Winter of 1855-1856. The Wakarusa War closed in December 1855. This second winter proved exceedingly severe, and many settlers were not sufficiently protected against the sudden and intense cold. Most of the houses were hastily constructed one-room log buildings with dirt floors, windows, and doors of cotton cloth. The storms drifted into these cabins through numberless chinks and cracks in roofs and walls. One of the pioneers, writing of that winter, said:

“At times, when the winds were bleakest, we went to bed as the only escape from freezing. More than once, we awoke in the morning to find six inches of snow in the cabin. To get up to make one’s toilet under such circumstances was not a very comfortable performance. Often, we had little to eat; the wolf was never far from our door during that hard winter of 1855-’56.”

Preparations for Hostilities. The struggle of the pioneers with the hardships of winter closed hostilities for a while. Still, it soon became evident that the Missourians were preparing more extensively than ever to invade Kansas, destroy Lawrence, and drive the Free-State people from the Territory or force them to recognize the pro-slavery Territorial Government. The Free-State people began to gather stores and ammunition and to send calls to the northern states for men and money to meet the situation.

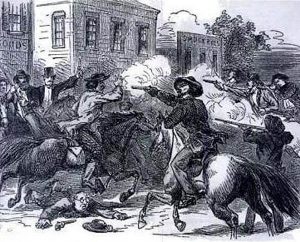

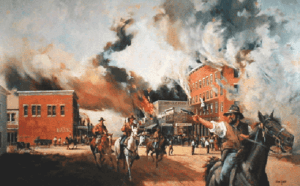

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856. several minor conflicts occurred. Sheriff Samuel Jones was wounded, a young Free-State man named Barber was killed and then came to the long-feared attack upon Lawrence. From the beginning, the policy of the Free-State people had been to avoid conflict wherever possible. They attempted to conciliate and pacify the attacking force on this occasion but in vain. As the pro-slavery leaders rode through the town, they were invited to dinner by Mr. Eldridge, the proprietor of the new $20,000 hotel built by the Emigrant Aid Company. They accepted the invitation, and the mob completely demolished the hotel in the afternoon. They threw the two printing presses of the town into the river, ransacked stores and houses, took whatever they wanted, and burned Governor Charles Robinson’s home before leaving town. The financial loss to Lawrence and the surrounding country was heavy. Though the people had been oppressed and outraged, they had not been conquered. By offering no resistance, they had robbed the affair of any possible justification in the eyes of the world.

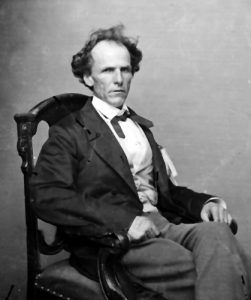

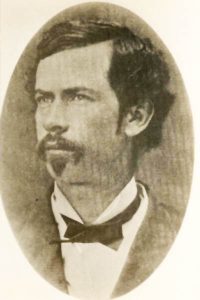

John Brown. There was one who bitterly opposed this policy of nonresistance, who believed that the way to meet the situation was to fight. This was John Brown, a tall, giant, grizzled old man who had come to Kansas a few weeks before the Sacking of Lawrence. Five sons had preceded him and had settled near Osawatomie. John Brown came not to aid his sons in their pioneer struggles nor to make a home for himself but because it seemed to him an opportunity to strike a blow at slavery. He hated slavery with an intensity that knew no bounds and gave all his mind and energy to warfare against it.

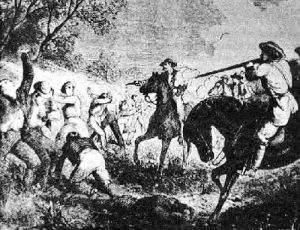

The Pottawatomi Massacre, May 24, 1856. The Sacking of Lawrence roused him to a high pitch of excitement. He believed this outrage should be avenged and determined to strike a blow, to return violence for violence. With a party of seven or eight men, including four of his sons, he made a night trip down Pottawatomi Creek, where several pro-slavery settlers lived. Five of these settlers were called out of their houses and killed.

Beginning of Four Months of Violence. This kind of warfare did not follow the plans or purposes of the leaders of the Free-State movement and was not approved by them. News of the awful affair spread rapidly through the Territory and created wild excitement. The Pottawatomi Massacre was followed by nearly four months of violence on both sides.

Both Sides Arm for War. A band of border ruffians gathered to wreak vengeance on those who had taken the lives of the pro-slavery settlers of Pottawatomi Creek. The Battle of Black Jack resulted in John Brown and his men defeating the border ruffians. The Missouri border hurriedly gathered more forces and marched a well-armed body of men into Kansas. The Free-State men had been busy, too, and on June 5, the Missourians were met by a band of armed Free-State Kansas settlers.

Armies Dispersed by the Governor. This alarming state of affairs aroused Governor Wilson Shannon, who ordered both sides to disperse. The Free-State army disbanded, but the Missourians obeyed sullenly. On their way back to Missouri, they committed several depredations and pillaged Osawatomie, which they hated because it was the home of John Brown.

Free-State Help from Northern States. The North was deeply stirred by the calamities endured by the Free-State people in Kansas. Although practically all of the free-state newspapers here had been closed or destroyed, the papers in the northern and eastern states were filled with narrations of the hardships, robberies, and murders that had befallen antislavery settlers in the Territory. The Kansas troubles were discussed from the pulpit, and the great preacher, Henry Ward Beecher, advised sending rifles to Kansas and pledged his church for a definite number. The men thus sent out armed with Bibles and rifles were sometimes called “The Rifle Christians.”

Public meetings were addressed by men fresh from Kansas, including ex-Governor Andrew Reeder, S. N. Wood, and James H. Lane. Much sympathy was aroused for the suffering Free-State settlers. Large sums of money were raised, and companies of men were organized to take part in the Territorial contest. The movement swept the states from Boston, Massachusetts, to the Northwest. “Societies of the semi-military cast, no less willing to furnish guns than groceries, sprang up as if by magic and overshadowed the earlier, more pacific organizations.” As a result of these agitations, a migration stream moved toward Kansas during the spring and summer of 1856. Every party came prepared for defense, and many brought a good stock of provisions. One writer said of the immigrants, “There were fewer women and children, less house luggage, fewer agricultural implements; more men, more arms, more ammunition.”

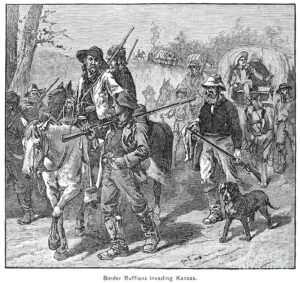

Missouri River Closed to Free-State Immigration. These activities of the North were viewed with alarm by the pro-slavery leaders. They believed this inflow of Free-State settlers must be checked, or it would end all hope of making Kansas a slave state. One of the most important measures they adopted for this purpose was closing the Missouri River to Free-State immigration. They overhauled the steamboats and seized merchandise and arms that were being sent to Free-State people, and they arrested and turned back all travelers whom they believed to be unfriendly to the South. All overland immigrants received similar treatment as soon as they touched Missouri soil.

New Route to Kansas. Although this policy occasioned the northern people considerable loss and much inconvenience, it did not check the movement toward Kansas. It simply meant that the immigrants entered Kansas from the north through Iowa and Nebraska. The Southerners also appealed to their people; money was raised, and men were sent to Kansas, but the response was not to be compared with the North’s.

A Condition of Lawlessness. While these things were going on, Kansas became more lawless. It would be hard to say which side surpassed the other in misdeeds. Several Free-State leaders, including Dr. Charles Robinson, were held at Lecompton during the summer as prisoners on a charge of treason. The Free-State people were irritated by losing money, supplies, and mail through the Missouri blockade. Bands of armed pro-slavery men guarded the roads out of Topeka and Lawrence so that these towns were really in a state of siege. These guards lived on supplies taken from the surrounding settlers and cut off supplies sent to the towns so that food became very scarce, especially at Lawrence, where the chief article of diet for some time was ground oats.

Meanwhile, supplies reached the pro-slavery towns Tecumseh, Lecompton, and Franklin without hindrance. It was evident to the Free-State people that their enemies expected to starve them out of the Territory, and they were destined to retaliate. The Free-State guerrillas again began seizing the supplies of pro-slavery settlers and merchants. This was kept up until many of the pro-slavery people were utterly impoverished.

The “Army of the North.” On August 1, a report that Lane was coming with the “Army of the North” spread over the Territory. James H. Lane was one of the Free-State men in the northern states, addressing meetings and raising men and money. He was a very eloquent speaker and influenced many to come to Kansas. The “Army of the North” consisted of several hundred men, women, and children, most of whom had come to make homes for themselves. This army combined several parties that had united to come into Kansas over the new route through Iowa and Nebraska. Lane was with the party, but only a small number were armed or had been gathered by him.

A pro-slavery Army Gathers. The pro-slavery leaders began to rally their men along the border. The following sentences are taken from one of the calls they published: “Lane’s men have arrived! Civil War is begun! And we call on all who are not prepared to see their friends butchered, to be themselves driven from their homes, to rally to the rescue.” Many men gathered on the border, anxiously awaiting permission to move into Kansas. Though Governor Shannon had dispersed the Missouri army a few weeks earlier, he refused to issue orders for the new army to move into the Territory.

Governor Shannon Resigns. At about this time, Governor Wilson Shannon resigned. He had so displeased the pro-slavery people that he was compelled to flee under cover of night. Daniel Woodson, Secretary of the Territory, became Acting Governor until the new governor arrived. As he was in full sympathy with pro-slavery interests, he opened the Territory to the Missouri invasion. Woodson’s power lasted only three weeks,

but they were the darkest days that Kansas had experienced.

The Burning of Osawatomie. The pro-slavery army moved into Kansas. The Pottawatomi Massacre had not been forgotten, and when this army reached Osawatomie, “the headquarters of old Brown,” they attacked the town. John Brown had only 41 men, and so thoroughly did the enemy do their work this time that only four cabins escaped burning.

Arrival of Governor Geary, September 1856. The new Territorial Governor, John W. Geary, arrived at this time. Governor Geary described the situation he found on his arrival in the following words: “I reached Kansas and entered upon the discharge of my official duties in the most gloomy hour of her history. Desolation and ruin reigned on every hand; homes and firesides were deserted; the smoke of burning dwellings darkened the atmosphere; women and children, driven from their habitations, wandered over the prairies and among the woodlands or sought refuge even among the Indian tribes. The highways were infested with numerous predatory bands, and the towns were fortified and garrisoned by armies of conflicting partisans, each excited almost to frenzy and determined upon mutual extermination. Such was, without exaggeration, the condition of the Territory at the period of my arrival.”

Conditions in the Territory. In the meantime, the extensive body of armed Missourians was moving forward, and the pro-slavery settlers were gathering in answer to a call that closed with these words: “Then let every man who can bear arms be off to the war again. Let it be the third and last time. Let the watchword be, ‘Extermination, total and complete.'” The Free-State people were scattered, unorganized, and scantily supplied with arms and provisions and were in no condition to meet such a force. Fortunately, the new Governor, whose policy was that of fair play, at once ordered all bodies of armed men to disband.

Preparations for the Defense of Lawrence. The Missourians, however, continued to move toward Lawrence. The Governor then took some United States troops and went to Lawrence, which he found almost defenseless. The town was poorly fortified, with few provisions and not more than ten rounds of ammunition. Even the women and children were armed. There were not more than three hundred people, but there seemed to be no thought of surrender. They would either repulse the enemy or perish in the attempt. The arrival of the Governor with United States soldiers brought unexpected relief.

End of the Reign of Violence, September 1856. On the morning of September 15, Governor Geary marched out to the Missouri army encamped about three miles from Lawrence, held a conference with the leaders, and insisted that his orders for disbanding be obeyed. The Missourians consented, and the force of 2,700 well-equipped men went home. Thus ended the four-month reign of violence that had begun with the sacking of Lawrence in May. The threatened attack on Lawrence was the last organized effort of the Missourians to take Kansas by force. Both sides soon gave up their plundering expeditions, travel became safer, and property became more secure. For a time, peace settled over the Territory. Governor Geary, believing that order was entirely restored to Kansas, appointed November 20 as a day of general praise and thanksgiving to Almighty God. With the close of the period of violence, a little less than two and a half years had passed since the organization of Kansas as a territory in the spring of 1854.

Summary. Hostilities were renewed in the spring of 1856. The Missourians prepared for invasion, and the Free-State people for defense. Several minor conflicts were followed by the sacking of Lawrence, to which the Free-State people offered no resistance. John Brown disapproved of this policy. He counseled revenge, and the Pottawatomi massacre followed. Then began a four-month “reign of terror.” Several conflicts followed, among them the battle of Black Jack. Each side hurriedly gathered an army, but Governor Shannon ordered them to disperse.

The sympathy of the whole North was aroused, and men and money poured into Kansas. This led to the closing of Missouri to Free-State travel, and the newcomers entered Kansas through Nebraska. Both sides committed many outrages during this time, and there was constant lawlessness. The coming of the “Army of the North” resulted in the gathering of a large army from Missouri called “the 2700.” Governor Shannon resigned, and Acting Governor Saniel Woodson permitted this army to enter Kansas, and it marched toward Lawrence, pillaging Osawatomie as it passed. While Lawrence was awaiting attack, Geary, the new Governor, arrived and ordered the army disbanded. This ended the period of violence.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated September 2023. Source: Arnold, Anna E.; The State of Kansas; Imri Zumwalt, state printer, Topeka, Kansas, 1919.

Also See:

Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War