Towns & Places:

Collyer

Ogallah

WaKeeney – County Seat

Bluffton Station on the Smoky Hill Trail

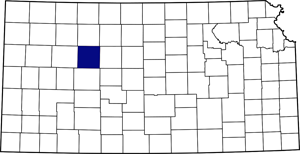

Trego County, Kansas, in the western part of the state, was once part of what was once known as the Great American Desert. It is the third county south of the Nebraska line and the fourth east of Colorado. Its county seat and largest city is WaKeeney.

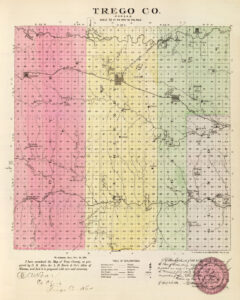

The general surface of the county is rolling, with some bluffs and broken lands along the Saline River in the north. In the east is Roundmound, an elevation of considerable height, and in the south are bluffs along the Smoky Hill River. Bottomlands are from one-half to one mile in width and comprise 12 percent of the area. A few small groves containing cottonwood, white ash, box-elder, elm, and hackberry comprise all the native timber. The Saline River enters in the northwest corner and flows east across the northern tier of townships into Ellis County. Trego and Springer Creeks are its principal tributaries from the south. The Smoky Hill River flows east across the southern portion, with Downer, Castle Hill, Wild Horse, and Elm Creeks being tributaries. Big Creek enters in the west and flows southeast into Ellis County. Magnesian limestone is abundant, and a very hard conglomerate stone exists in some localities. Native lime is abundant, and chalk and coal were found to some extent.

Long before the county was officially created, the Smoky Hill Trail was established in 1859 to cross the Great Plains of Kansas to Colorado during the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush. The trail ran from Atchison, Kansas, on the Missouri River to Denver, Colorado. For most of the way, it followed the Smoky Hill River.

In 1865, David Butterfield established the Butterfield Overland Despatch, hauling freight and passengers from Atchison to Denver, following the Smoky Hill River on its north side. The trail came right through Trego County from mile 284 to 305, and six stagecoach stations were located in the county. These included Bluffton Station, Stormy Hollow, White Rock, Downer, Ruthton, and Castle Rock Creek Station. While the buildings are long gone, visitors can still find evidence left by the original pioneers at some locations. The trail can be traced today by following the limestone posts marking the trail. Bluffton Station, located in Threshing Machine Canyon at Cedar Bluffs Reservoir, was a popular place for travelers to camp, and names etched into the rocks dating back to 1849 can still be seen.

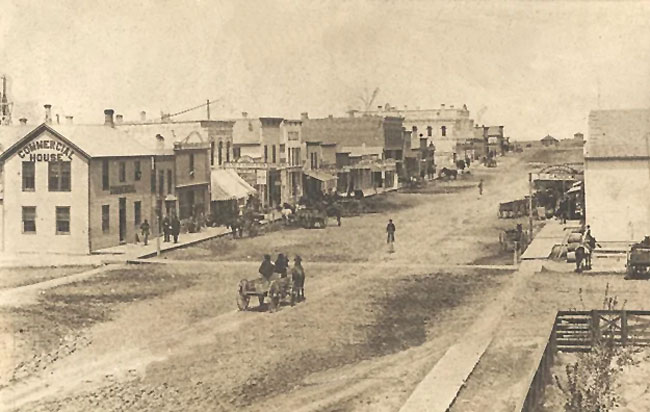

The first settler was B. O. Richards, who was located at Coyote, near the present town of Collyer, in about 1876. In 1877, more settlers came, including J. R. Snyder, J. C. Henry, Harlow Orton, Earl Spaulding, J. K. Snyder, D. O. Adams, George Brown, George McCaslin, and George Pinkham. The same year, advance agents of a colony from Chicago, Illinois, arrived, including Mr. Warren, W. S. Harrison, George Barrell, F. O. Ellsworth, Thomas Peak, and C. W. F. Street. The following year, there was a rush of immigrants, most of whom were from the Chicago vicinity. The influx continued through the first half of 1879, the population reaching 3,500 by midsummer.

The county was created from unorganized territory by Edgar Poe Trego, Albert F. Warren, and James Keeney. It was named in honor of Captain Edgar P. Trego of the Eighth Kansas Infantry. On June 21, 1879, it was made official when Governor John P. St. John issued a proclamation. At that time, Wakeeney was named as the county seat. The first meeting of the board of commissioners and election was held on June 26, 1879. At that time, the county was divided into the townships of Ogallah, Collyer, and Wakeeney, and Wakeeney was made the permanent county seat. County officers were also elected.

The county is about 30 miles square and contains 570,000 acres or 900 square miles. When the county first began to be settled, buffalo, elk, and antelope roamed over its plains in countless numbers.

The first church founded in the county was the Presbyterian Church in WaKeeney in 1878.

In September 1878, a tribe of Cheyenne moving northward were committing outrages in western Kansas, including killing men, outraging and murdering women, and stealing cattle. People from the country flocked into WaKeeney in fear and confusion. Arms and munitions were sent out from Topeka, Kansas. A company of 80 men was organized, of which John M. Keeney was Captain, W. H. Fuson was First Lieutenant, and C. W. Mulford was Second Lieutenant. The company was named the Trego County Home Guards and was ready to defend WaKeeney against any attack the Indians might make. In their northward march, the Cheyenne kept to the west of Trego County, crossing the railway track about 25 miles west of Wakeeney at Buffalo Park in Gove County, in the vicinity of which the Indians killed 52 men, women, and children.

The poor crops of 1879 brought about a poor reaction and settlers who had come with the expectation of raising a field crops left in large numbers. Those who remained raised stock and were successful. Crops continued to do poorly in the next few years, and hog raising was also found not to be profitable, at which time, attention was given principally to cattle and sheep, especially the latter.

Before the counties of Gove, Logan, and Wallace were officially organized, they were attached to Trego for judicial purposes. In 1881, some trouble was caused by thieves and marauders committing crimes in the territory over which no court had jurisdiction. Three murderers and several horse thieves were turned over to the sheriff of Trego County, but they had to be set free as there was no authority to try them.

On March 15, 1882, a disagreement occurred at a place known as Gopher, which ended tragically. The parties engaged were two brothers, named John and Thomas Pitman, a man named Thomas B. Wooton, another named James McCullom, and one named John Evarts. Wooton and McCullom had been employed by the railway company but had been discharged and were notified to leave the country.

It is unclear how the trouble began, but John Pitman was killed, his brother Thomas badly wounded, and John Evarts wounded in the face. McCullom and Wooton fled, and the State offered a reward of $500 for their arrest and conviction. Joseph Lucas, who was then Deputy Sheriff, in the absence of Mr. Allen, the Sheriff, who was off on other duty, went with a warrant and arrested William Wooton, a brother of Thomas Wooton and the wife of the latter. After taking this party into custody, word was sent to the Sheriff of Trego County that Thomas Wooton, one of the murderers, had been arrested and was in custody in Lakin, in Kearney County. James McCullom was killed in a fight with the Sheriff of Ford County, by whom Wooton had been arrested.

Deputy Lucas started to Kearney County after Wooton, whom he found to be suffering from quite a severe wound in the shoulder, received in the fight with the Sheriff when McCullom was killed. Lucas brought Wooton back to Wakeeney and, waiving an examination, was ordered to be taken to the Ellis County jail. The first train East was due at 3:30 in the morning, and that night while Deputy Lucas was sitting in the Union House with his three prisoners, all of whom were hand-cuffed, awaiting the train’s arrival, he happened to fall into a light sleep. While sleeping, he received a blow over the head, which knocked him from his chair. Gathering himself up, he saw several masked men in the hotel’s office with whom he entered into a general fight. They fought through the office and out onto the porch, keeping it up back through the hall and into the parlor, from which they emerged into the dining room where tables were over-turned, dishes were broken, the stove upset, and where Mr. Lucas received a blow on the head which knocked him senseless. While the fight was going on, a rope was thrown around Wooton’s neck, and he was dragged out and taken to an empty box car, on which the masked party had arrived from the West. From this point, the fate of Wooton is in doubt, some contending that he was lynched. Others said that while in the box car, he seized the revolver of one of his captors and immediately commenced firing, killing two of the party and wounding some of the others, after which he jumped from the car with the rope still around his neck, and made his escape.

In the fall of 1882, word was sent to Sheriff Allen at Wakeeney that a party had started northward from Fort Supply in the Indian Territory with about 20 stolen horses and for him to look out for them. Sometime after this, one evening just about dark, two men rode into Wakeeney leading 21 head of horses, and as soon as Sheriff Allen saw them, he was satisfied they were the parties he had been looking for. Not having a warrant, he did not arrest them that night, and the following morning, bright and early, he procured a warrant, hired a livery team, and, taking a man with him to drive, started in pursuit.

The thieves had “hobbled” the horses, that is, fastened their forelegs together, and their progress was relatively slow. Before they had gotten out of Trego County, the Sheriff had overtaken them. While yet a little way from them, the Sheriff, to save the team he was driving from being shot, got out and, taking his Winchester rifle in his hand, started after them on foot. When within about 50 yards of them, he called to them to “throw up,” to which they responded by wheeling around and opening fire upon him from two rifles. He returned the fire and unhorsed one of them, who went by the name of Jones, the first shot killing his horse. Upon Jones being unhorsed, he ran and placed himself behind a slight elevation in the ground from which he kept up his fire. A shot from the sheriff’s rifle took effect on Jones’ cheek, after which he “threw up” and surrendered. The second thief, who was none other than the notorious Dick Edwards, wheeled his horse and galloped off upon seeing Jones surrender.

The Sheriff fired after as he ran, the bullet hitting the neck of the horse that Edwards was riding. While the skirmish was going on, the “hobbled” horses had gone on about three-fourths of a mile, and Edwards, seeing that his only chance for escape was to secure another horse, put spurs to his wounded and fast-sinking animal and barely succeeded in reaching the drove when the horse he had ridden dropped dead. It required but a moment to cut the rope by which one of the horses was hobbled, change saddles, and escape. In the meantime, Sheriff Allen succeeded in capturing all of the stolen horses, except two that were killed and the one upon which Edwards escaped. He also secured Jones, one of the thieves, who was placed in the Ford County jail to await his trial, which was scheduled to take place in March 1883.

The first school district was formed in WaKeeney in 1884.

In 1884, Colonel Cyrus. K. Holliday of Topeka sent two prospectors into Trego County to look for mineral deposits. They found traces of zinc and other minerals but not in paying quantities. A great boom was occasioned in 1902-03 by discovering an element in the shale of Trego County, which was thought to be gold. Professor Ernest Fahrig of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, claimed to have a process by which he could remove the gold from the shale. A company was formed, capitalists being eager to buy stock. There proved to be no gold in the shale, and by 1904, the whole affair had passed into history.

In 1889, the Trego County Courthouse was built at the cost of $40,000.00. It was said to be the finest Courthouse west of the Missouri River at that time.

The county was divided into seven townships at some point, including Collyer, Franklin, Glencoe, Ogallah, Riverside, Wakeeney, and Wilcox.

In 1910, the main line of the Union Pacific Railroad entered in the east near the center and crossed northwest to Wakeeney, then west into Gove County, a distance of 33 miles.

The number of acres of land under cultivation in 1910 was 338,502, with the principal crop being wheat. At that time, the county’s population was 5,398.

The county’s population peaked at 6,470 in 1930.

The severe drought of the 1930s and early 1940s in western Kansas focused national attention on the plight of area farmers, who depended entirely on dry farming. This created the demand for irrigation projects and new sources of municipal water supplies. In response, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation began investigating the Smoky Hill River basin in 1941 to determine what would be feasible. However, the outbreak of World War II halted the effort.

Cedar Bluff Reservoir was authorized by the Flood Control Act of 1944. Investigations resumed in 1946, and by the end of the year, detailed topographic surveys were complete. Plans were soon made to construct the dam, distribution systems for irrigation, flood control, fish and wildlife enhancement, recreation, and municipal and industrial uses. Bids were opened on February 8, 1949, and after hiring a contractor, work began on April 1, 1949. The work was completed on September 29, 1951, and filled that same year.

The Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks, and Tourism manages 9,300 acres of land around the reservoir as the Cedar Bluff Wildlife Area. The department also operates the 850-acre Cedar Bluff State Park located on the reservoir’s eastern end. Today, the reservoir welcomes over 250,000 people each year to enjoy water sports, fishing, camping, hiking, and more.

Trego County includes several sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Collyer Downtown Historic District, St. Michael School & Convent in Collyer, and the one-room Wilcox School south of WaKeeney.

As of the 2020 census, the county population was 2,808.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2023.

Also See:

Butterfield Overland Despatch – Staging on the Smoky Hill Trail

Sources:

Kansas State Historical Society

Wikipedia

WaKeeney Travel Blog