When Christopher Columbus discovered America, the continent north of Mexico was inhabited by four great groups of aborigines, given the general name of “Indians,” the discoverers believed they had circumnavigated the earth and arrived at the eastern border of India. The Algonquin group, probably the most important of the four, inhabited a triangle which may be roughly described by a line drawn from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to the Rocky Mountains, then by a line from that point to the Atlantic coast near the Neuse River, and up the coast to the place of beginning. Also, within this triangle lived the Iroquoian group, whose habitat was along the Lakes Erie and Ontario shores, extending to the lower Susquehanna River and westward into Illinois.

South and east of the triangle were the tribes of the Muskhogean stock, the Creek, Choctaw, etc. West of all these lay the Siouan group.

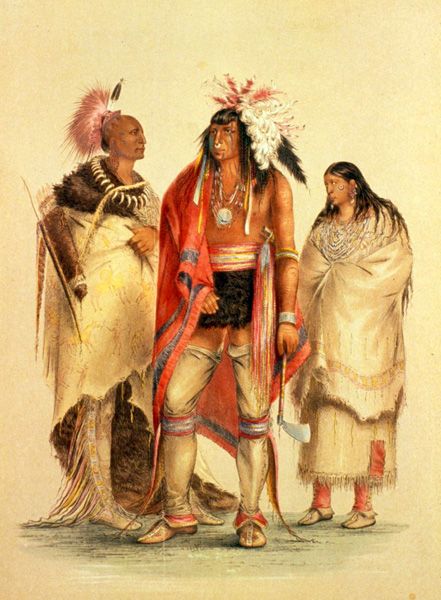

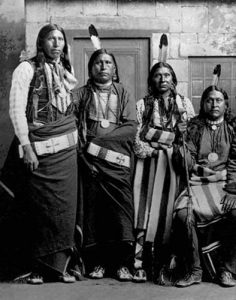

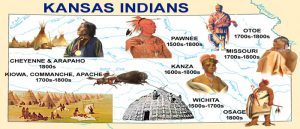

When the first white men visited the region now comprising the State of Kansas, they found it inhabited by four tribes of Indians: the Kanza or Kaw, which occupied the northeastern and central part of the state; the Osage, who were located south of the Kanza; the Pawnee, whose country lay west and north of the Kanza, and the Comanche, whose hunting grounds were in the western part of the state.

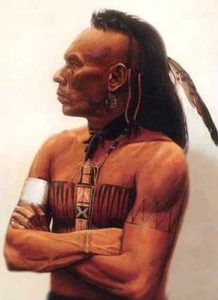

A handbook issued by the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1907 defined the Kanza as “A southwestern Siouan tribe.” Their linguistic relations are closest to the Osage and close to the Quapaw. In the traditional migration of the group, after the Quapaw had first separated from there, the main body divided at the mouth of the Osage River, the Osage moving up that stream and the Omaha and the Ponca crossing the Missouri River and proceeding northward, while the Kanza ascended the Missouri River on the south side of the mouth of the Kansas River.”

The 15th annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology said: “According to tribal traditions collected by Dorsey [Indians of The Southwest, 1903], the ancestors of the Omaha, Ponca, Quapaw, Osage, and Kanza were originally one people dwelling on the Ohio and Wabash Rivers, but gradually working westward. The first separation took place at the mouth of the Ohio River. Those going down the Mississippi River became the Quapaw or “dawn stream people,” and those who went up became the Omaha or “upstream people.”

After the Kanza separated from the Omaha and Ponca and established themselves at the mouth of the Kansas River, they gradually extended their domain to the present northern boundary of Kansas, where they were met and driven back by the Ioway and Sauk tribes, who had already come in contact with the white traders from whom they had received firearms. Without these superior weapons, the Kanza were forced back to the Kansas River. Here, they were visited by the “Big Knives,” as they called the white men, who persuaded them to go farther west. The tribe then successfully occupied some 20 villages along the Kansas Valley before settling at Council Grove, where they were finally removed to the Indian Territory in 1873.

The first white man to acquire knowledge of the Kanza Indians was Spanish Conquistador Juan de Onate, who met them on his expedition in 1601 and referred to them as the “Escansaques.”

Although French missionary Jacques Marquette’s map of 1673 showed the location of the Kanza Indians, the French did not come in contact with the tribe until 1750, when the French explorers and traders ascended the Missouri River to the mouth of the Kansas River, where they met with a welcome reception from the Indians.

These early Frenchmen gave the tribe the name of Kah or Kaw, which, according to the story of an old Osage warrior, was a term of derision, meaning coward. They were given to the Kanza by the Osage because they refused to join in a war against the Cherokee. Another Frenchman, Etienne Venyard Sieur de Bourgmont, who visited the tribe in 1724, called them the “Canzes” and reported that they had two villages on the Missouri River, one about 40 miles above the mouth of the Kansas River and the other farther up the river, both on the right bank. Lewis and Clark also mentioned these villages nearly a century later.

George J. Remsburg, who was regarded as an authority on matters relating to the Kanza Indians, said the grand village of the tribe was located where the town of Doniphan now stands and was known as the “Village of the Twenty-four.” After the white settlers induced them to remove farther west, the principal village of the tribe was near the southwest corner of Pottawatomie County. In the spring of 1880, Franklin G. Adams, Secretary of the Kansas Historical Society, surveyed this village. His report stated that the old village was “about two miles east of Manhattan, on a neck of land between the Kansas and Big Blue Rivers.

The 15th annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology said there was a Kanza village at the Saline River’s mouth and that the first treaty between them and the United States was concluded there. After the treaty of 1825, the tribes moved east again and, in 1830, had two villages near the mouth of Mission Creek, a short distance west of Topeka. The village of American Chief, containing some 20 lodges and 100 followers, was on the west side of the creek about two miles from the Kansas River. Hard Chief’s village, nearer the river, had some 500 or 600 inhabitants, and a third village of Fool Chief was located on the north side of the Kansas River, not far from the Menoken Union Pacific Railroad station.

In 1847, several remnants of the tribe were ordered to what was known as the “diminished reserve” at Council Grove. Concerning this movement on the part of the government of the United States, George P. Morehouse, in his Kanza Indians and Their History, said: “It was not only a blunder, but it was criminal after cheating them out of their Kansas Valley homes, to remove them to Council Grove. Here, they were placed near a trading center on the Santa Fe Trail, where their contact with piejene (fire-water), the whiskey of the whites, and other vices, proved far more harmful than any knowledge of civilization received could overcome. Here, they were neglected religiously, and only experiments of a brief nature were undertaken for their education.”

Among the Kanza, the gentile system prevailed. There were seven tribal subdivisions, and these were still further divided into 16 clans, including Manyinka (earth lodge), Ta (deer), Panka (Ponca), Kanza, Wasabe (black bear), Wanaghe (ghost), Kekin (carries a turtle on his back), Minkin (carries the sun on his back), Upan (elk), Khuga (white eagle), Han (night), Ibache (holds the firebrand to the sacred pipe), Hangatanga (large Hanga), Chedunga (buffalo bull), Chizhuwashtage (peacemaker), Lunikashinga (thundering people).

Ethnologically, the Osage were closely allied to the Kanza. Geographically they were divided into three bands — Pahatsi (great), Utsehta (little), and the Santsukhdi band, which lived in Arkansas. Marquette’s map of 1675 showed the tribe located on a stream believed to be the Osage River, and other explorers and writers located them in the same place. In 1686 Donay mentioned 17 villages of the Osage. Eight years later, Father Jaques Gravier wrote from the Illinois Mission that the tribe had but one village, the other 16 being mere hunting camps occupied only at intervals. Iberville, in 1701, gave an account of a tribe of some 1,500 families living in the region of the Arkansas River, near the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, and like them, speaking a language that he took to be Quapaw.

French explorer Jean La Harpe said the Osage were a warlike tribe that kept the Jean La Harpe Caddooan tribes in a state of terror. However, when the Illinois Indians were driven across the Mississippi River by the Iroquois, they found shelter with the Osage Nation.

Early in the 18th century, French traders visited the Osage and made peace treaties with the tribe that lasted for years. In 1714, some of the Osage warriors assisted the French against the Fox Indians at Detroit. In 1806, a Little Osage chief named Chtoka (Wet Stone) told Lieutenant Zebulon Pike that he was at the defeat of General Braddock in 1755 with all the warriors of his tribe that could be spared from the village.

Some historians believe that the Osage Nation was originally one people. According to Lewis and Clark, about half of the Great Osage, under a chief named Big Track, migrated to the Arkansas River about 1802 and laid the foundation of the Santsukhdi band. Two years after this separation, Lewis and Clark found the Great Osage, numbering 500 warriors, in a village on the south side of the Osage River and the Little Osage, numbering 250 or 300 warriors, about six miles distant on the Arkansas River and one of its tributaries called the Vermilion River. The present Osage reservation was established in 1870.

The Indian name of the tribe was Wazhaze, which the French corrupted into Osage. A tribal tradition relates that originally, the nation consisted of two tribes — the Tsishu, or peace people, and the Wazhaze, or true Osage. The Tsishu lived on a vegetarian diet, while the Wazhazelatter, a war people, ate meat. After a time, the two tribes began to trade with each other. The Tsishu later met a warlike people called the “Hangda-utadhantse,” with whom they made peace, and all three were then united under the general name of Wazhaze. After the consolidation, the tribe was divided into 14 bands — seven of the former Tsishu, five of the Hangda, and two of the Wazhaze, so that the number of bands of the peace and war people was equal.

The Pawnee Nation was a confederacy of tribes belonging to the Caddoan family and called themselves Chahiksichahiks, “men of men.” As the Caddoan tribes moved northeast, the Pawnee separated from the main body near the Platte River in Nebraska. Their traditions say they acquired territory by conquest and where the Siouan tribes subsequently found them.

There are some questions about the origin of the name “Pawnee.” The word Pani, which has become synonymous with Pawnee, means “slave.” From this tribe, the Algonquian tribes around the Great Lakes obtained their slaves, and some writers maintain that the word Pawnee is equivalent to the word slave. The tribal name resulted from so many members being subjected to a state of bondage.

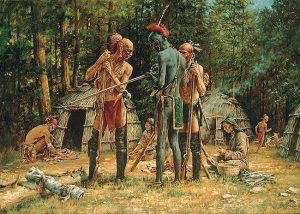

The tribal organization of the Pawnee was based on the village communities, which represented subdivisions of the tribe. Each village had its name, hereditary chiefs, a shrine, priests, etc. The dominating power in their religion was Tirawa (father), whose messengers were the winds, thunder, lightning, and rain. Pawnee lodges were of two types — the common form of skins stretched over a framework of poles and the earth lodge. The latter was circular, 30 to 60 feet in diameter, partly underground, and elaborate religious ceremonies usually accompanied its construction. Among the men, the only essential articles of wearing apparel were the breechcloth and moccasins, though a robe and leggings supplemented these in cold weather or on state occasions. After marriage, a man lived with his wife’s family, though polygamy was not uncommon.

Juan de Onate, in his account of his expedition in 1601, says the Escansaques and Quivirans were hereditary enemies, and Professor Dunbar of the Kansas Historical Society demonstrated almost to an absolute certainty that the Quivirans mentioned by Onate were the Pawnee, who were also the inhabitants of the ancient Indian province of Harahey. The first Pawnee to come in contact with the white man was the one whom the Spaniards of Coronado’s Expedition called “the Turk.” Soon after the expedition of Onate, the Spanish settlers of New Mexico became acquainted with Pawnee through their raids into the white settlements for horses. The Spaniards tried to establish peaceful relations with the tribe for two centuries but only partially succeeded. Consequently, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Pawnee villages were so remote from the white settlements that they escaped the generally fatal influences of the aborigines.

In 1702, the estimated Pawnee population was about 2,000 families. When Louisiana was purchased from France by the United States a century later, the Pawnee country was south of the Niobrara River in Nebraska, extending southward into Kansas. On the west were the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, on the east were the Omaha, and south were the Otoe and Kanza. Soon after the Louisiana Purchase, the Pawnee came in contact with white traders from St. Louis. In September 1806, Lieutenant Pike lowered the Spanish flag and raised the United States flag at the Pawnee village in Republic County, Kansas. In 1838, the number of Pawnee was estimated at 10,000, but in 1849, the tribe was reduced to about 4,500 by a cholera epidemic. Five years before this, however, they ceded to the United States their lands south of the Platte River and were removed from Kansas. Between 1873 and 1875, what remained of the tribe was settled upon a reservation in the Indian Territory. At that time, about 1,000 represented four tribes of what was once the great Pawnee Confederacy.

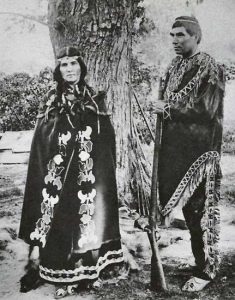

As shown by their language and traditions, the Comanche, who inhabited western Kansas early in the 18th century, was an offshoot of Wyoming’s Shoshone. The Siouan name was Padouca, by which they were called in the accounts of the early French explorers, notably Bourgmont, who visited the tribe in 1724. As late as 1805, the North Platte River was known as the Padouca Fork. At that time, the Comanche roamed over the country about the headwaters of the Arkansas, Red, Trinity, and Brazos Rivers in Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. According to a Kiowa tradition, the Arkansas River formed the Comanche country’s northern boundary when they moved southward from the country about the Black Hills.

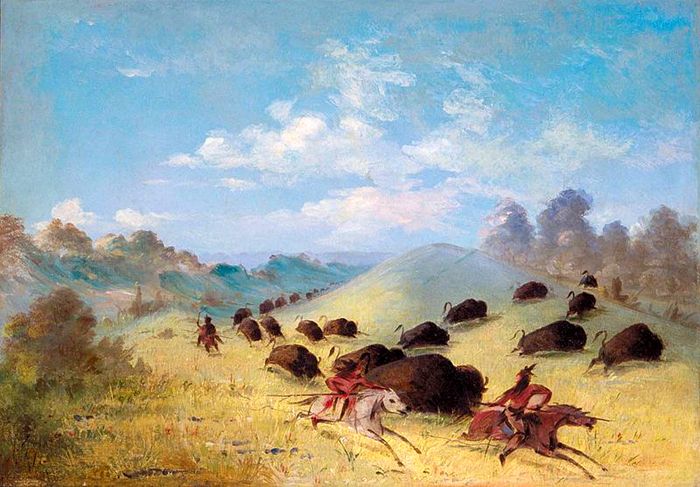

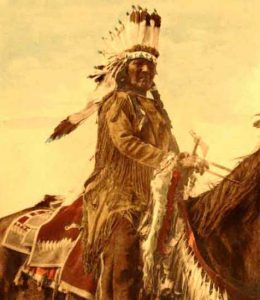

For nearly two centuries, the Comanche were at war with the Spaniards of the southwest and made frequent raids as far south as Durango. They were generally friendly with the Americans but did not like the Texans. The Comanche were probably never a large tribe, as they did not settle down in villages but lived as nomadic buffalo hunters, following the herds as they grazed from place to place. They were fine horsemen, the best riders on the plains, full of courage and with a high sense of honor. They considered themselves superior to the tribes they associated with. In 1867, they were given a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma, but they did not go to it until after the outbreak of the plains tribes in 1874-75.

The Cheyenne belonged to the Algonquian family. They are first mentioned in history as “Chaa,” some visiting La Salle’s Fort on the Illinois River to invite the French to their country where beaver and other fur-bearing animals were plentiful. They inhabited the region bounded by the Mississippi, Minnesota, and upper Red Rivers. According to Sioux tradition, the Cheyenne occupied the upper Mississippi country before the Sioux. When the latter appeared in that locality, there was some friction between the two tribes, which resulted in the Cheyenne crossing the Missouri River and locating around the Black Hills, where Lewis and Clark found them in 1804.

From there, they drifted westward and southward, first occupying the region about the headwaters of the Platte River and next along the Arkansas River in the vicinity of Bent’s Fort, Colorado. A portion of the tribe remained on the Platte and the Yellowstone Rivers and became known as the Northern Cheyenne.

The Cheyenne have a tradition that when they lived in Minnesota, before the coming of the Sioux, they lived in fixed villages, practiced agriculture, made pottery, etc. Still, everything changed when the tribe was driven out, and they became roving hunters. The only institution of the old life that remained with them was the great tribal ceremony of the Sun Dance.

In 1838, the Cheyenne and Arapaho attacked the Kiowa on Wolf Creek, Oklahoma. Two years later, peace was established between the tribes, after which the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa Comanche, and Apache were frequently allied in wars against the whites.

The Northern Cheyenne joined the Sioux in the Sitting Bull War of 1876. In the winter of 1878-79, a band of the northern Cheyenne was taken as prisoners to Fort Reno, Oklahoma, to be colonized with the southern Cheyenne in Oklahoma. The Chiefs Dull Knife, Wild Hog, and Little Wolf, with about 200 followers, escaped and were pursued to the Dakota border, where most of the warriors were killed.

In February 1861, the Cheyenne and Arapaho relinquished their title to lands in Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, and northwest Kansas, and in 1867, the southern Cheyenne were given a reservation in western Oklahoma. However, they refused to occupy it until after the surrender of 1875, when some of their leaders were sent to Florida as a final means of quelling the insurrection. In 1902, southern Cheyenne was allotted land in several areas. Two years later, the Bureau of Ethnology reported 3,300 members of the tribe — 1,900 southern and 1,400 northern.

The Arapaho, a plains tribe of the Algonquian group, was closely allied with the Cheyenne for almost a century. They were called by the Sioux and Cheyenne “Blue Sky Men” or “Cloud Men.” An Arapaho tradition tells how the tribe was once an agricultural people in northwestern Minnesota but were forced across the Missouri River, where they met the Cheyenne, with whom they moved southward. Like the Cheyenne, they became divided, the northern Arapaho remaining about the mountains near the Platte River’s head and the southern branch drifting to the Arkansas River. In 1867, the southern portion of the tribe was given a reservation with the southern Cheyenne in Oklahoma. By 1892, they had made sufficient progress to justify the government in allotting them lands in severalty and the rest of the reservation being thrown open to white settlement. The northern branch was established in 1876 on a reservation in Wyoming.

Between 1825 and 1830, the Kanza and Osage tribes withdrew from a large part of their lands, which were turned over to the United States. This allowed the national government to establish the long-talked-about Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. Congress, therefore, passed a bill that provided that the country west of the Mississippi River, which was not included in any state or organized territory of the United States, be set apart as a home for the Indians. This Indian Territory joined Missouri and Arkansas on the west and was annexed to those states for judicial purposes. During the decade following the bill’s passage, several eastern tribes found what they thought were permanent homes within the present State of Kansas. The Shawnee, Delaware, Ottawa, Miami, Chippewa, Kickapoo, Sauk and Fox, Wyandot, and others were among them.

The Shawnee were the first to seek a home in the new territory. The early history of the Shawnee tribe is somewhat obscure. However, it was known to be an important tribe in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Tennessee, South Carolina, and along the Savannah River in Georgia. Some writers claim that the Shawnee were identical to the Erie of the early Jesuits, and attempts have been made to show that they were allied to the Susquehannock of the Iroquois family. Their language was that of the central Algonquian dialects — similar to that of the Sauk and Fox — and the Delaware had a tradition that made the Shawnee and Nanticoke one people.

The Shawnee’s recorded history began in about 1670, when two bodies were some distance apart, with the friendly Cherokee Nation between them. In 1672, the western Shawnee allied with the Susquehannock in a war against the Iroquois. Twelve years later, the Iroquois made war on the Miami tribe because they tried to ally with the Shawnee to invade the Iroquois country.

About the middle of the 18th century, the eastern and western Shawnee were united in Ohio, and from that time to the Treaty of Greeneville in 1795, they were almost constantly at war with the English. They were driven from the head of the Scioto River to the head of the Miami River. After the Revolutionary War, some of them went south and formed an alliance with the Creek Indians, with whom they were closely connected, their language being almost identical. Others joined with a portion of the Delaware tribe and accepted a Spanish invitation to occupy a tract of land near Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

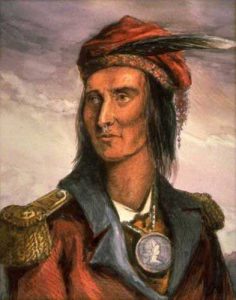

In the early part of the 19th century, the Shawnee in Indiana and Ohio, with some of the Delaware, joined the movement of the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh and his brother, Tenskawata (the Prophet), to unite the tribes of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys in a general uprising against the whites. General Harrison effectually crushed the conspiracy at the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 4, 1811. In the War of 1812, some of the Shawnee fought with the British until Tecumseh was killed at the Battle of the Thames.

The fall of their great war chief broke the tribe’s warlike spirit, and the Shawnee sued for peace. In 1825, the Missouri Shawnee sold their lands and received a reservation in Kansas south of the Kansas River and bordering on the Missouri River.

The Ohio Shawnee sold their lands near Wapakoneta in 1831 and joined their brethren in Kansas, the mixed band of Shawnee and Seneca coming in about the same time. Some of the tribe withdrew from the Kansas reservation in 1845 and went to the Canadian River in Oklahoma. They became known as the “Absentee Shawnee.” In 1867, those with the Seneca moved to the Indian Territory, and in 1869, the main body was incorporated with the Cherokee Nation.

The Shawnee tribe consisted of five divisions, which were further divided into 13 clans, the English names of which were the wolf, loon, bear, buzzard, panther, owl, turkey, deer, raccoon, turtle, snake, horse, and rabbit. The Clan of the Turtle was the most important, especially in their mythological traditions.

The Delaware, formerly the most important confederacy of the Algonquian stock, occupied the Delaware River’s entire valley. They called themselves the Lenape or Leni-Lenape. The English gave them the name of Delaware, and the French called them Loups (wolves). They were divided into three bands — the Munsee, Unami, and the Unalachtigo — though it is probable that some of the bands in New Jersey may have formed a fourth group.

About 1720, the Iroquois tribe assumed authority over the Delaware and forbade them from selling their lands. This condition lasted until after the French and Indian War. Then, the white men gradually crowded them westward and began to form settlements in Ohio along the Muskingum River with the Huron.

Here, they were supported by the French and became independent of the Iroquois. They opposed the English with determination until the Treaty of Greeneville in 1795. Six years before that treaty was consummated, Louisiana’s Spanish government permitted the Delaware to settle in that province, near Cape Girardeau, Missouri, with some of the Shawnee tribe.

In 1820 there were two bands — numbering about 700 — in Texas, but by 1835 most of the Delaware were settled upon their Kansas reservation between the Kansas and Missouri Rivers. Their title to this reservation was finally extinguished in 1866, and on April 11, 1867, President Johnson approved an agreement by which the Delaware merged their tribal existence with the Cherokee Nation.

In 1820, an ancient hieroglyphic bark record giving the traditions of the Delaware tribe was found. This old record was translated and published in 1885. It gives an account of the creation of the world by great Manito and of the flood, in which Nanabush, the Strong White One, grandfather of men, created the turtle, on which some were saved. This book is known as the “Walam Olum.”

The Munsee, one of the three principal divisions of the Delaware, originally occupied the country about the Delaware River’s headwaters. By what was known as the “walking purchase,” in about 1740, they were defrauded from the greater portion of their lands and forced to move. They obtained lands from the Iroquois on the Susquehanna River, where they lived until the Indian country was established by the act of 1830, when they removed to what is now Franklin County, Kansas, with some of the Chippewa. The Bureau of Ethnology report for 1885 says the only Munsee then recognized officially by the United States were 72, living in Franklin County, Kansas. All the others had been incorporated with the Cherokee Nation.

According to one of their traditions, the Ottawa were once part of a tribe to which also belonged the Chippewa and Potawatomi, all of the great Algonquian family. They moved as one tribe from their original habitat north of the Great Lakes and separated about the straits of Mackinaw. Another account says that when the Iroquois destroyed the Huron Indians in 1648-49, the Huron found refuge with the Ottawa, which caused the Iroquois to turn on that tribe. The Ottawa and the Huron then fled to Green Bay, where they were welcomed by the Potawatomi, who had preceded them to that locality.

The tribe is mentioned in the Jesuit Relations as early as 1670, when Father Dablon, superior of the mission at Mackinaw, said: “We call these people Upper Algonkin to distinguish them from the Lower Alkonkin, who are lower down in the vicinity of Tadousac and Quebec. People commonly give them the name of Ottawa because, of more than 30 different tribes found in these countries, the first that descended to the French settlements were the Ottawa, whose name afterward attached to all the others.”

After a time, the Ottawa and Huron went to the Mississippi River and established themselves on an island in Lake Pepin. The Sioux soon drove them out and went to the Black River in Wisconsin, where the Huron built a fort, but the Ottawa continued east to Chequamegon Bay. In 1700, the Huron were located near Detroit, and the Ottawa were between that post and the Saginaw Bay. The Ohio Ottawa were removed west of the Mississippi River in 1832.

The following year, by the Treaty of Chicago, those living along the west shore of Lake Michigan ceded their lands there and were given a reservation in Franklin County, Kansas, the county seat of which bears the tribe’s name. In 1906, about 1,500 Ottawa residents lived in Manitoulin and Cockburn Islands, Canada; 197 were under the Seneca school in Oklahoma, and nearly 4,000 were in Michigan.

The Chippewa or Ojibway formerly ranged along Lake Superior and Lake Huron’s shores, extending across Minnesota to the Turtle Mountains in North Dakota. When America was discovered, the Chippewa lived at La Pointe, Ashland County, Wisconsin, on the south shore of Lake Superior, where they had a village called Shangawaumikong.

Early in the 18th century, the Chippewa drove the Fox tribe from northern Wisconsin and drove the Sioux west of the Mississippi River. Other Chippewa overran the peninsula lying between Lake Huron and Lake Erie and forced the Iroquois to withdraw from that section. There were ten principal divisions of the tribe scattered through Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and North Dakota, with more than 20 bands. Before 1815, the Chippewa were frequently engaged in war with the white settlers, but they remained peaceful after the treaty of that year.

In 1836, during what was known as the Swan Creek and Black River, Chippewa sold their lands in southern Michigan and moved to the Munsee Reservation in Franklin County, Kansas. In 1905, the Bureau of Ethnology estimated the number of Chippewa in the United States and Canada at 30,000, about half of whom were in the United States.

One of the most important of the Algonquian tribes, the Miami, was called by some of the early chroniclers the “Twightwees.” The region over which they roamed was once outlined in a speech by their famous chief, Little Turtle, who said: “My fathers kindled the first fire at Detroit; then they extended their lines to the headwaters of the Scioto; then to its mouth; then down the Ohio River to the mouth of the Wabash River, and then to Chicago over Lake Michigan.”

The men of the Miami tribe have been described as “of medium height, well built, heads rather round than oblong, countenances agreeable rather than sedate or morose, swift on foot and excessively fond of racing.” The women spun the thread of buffalo hair, which they made into bags to carry provisions when on a march. Their deities were the sun and the thunder, and they had but a few minor gods. Six bands of the Miami were known to the French, the principal ones being the Piankashaw, Wea, and Pepicokia.

French Explorer Sieur de La Salle first mentioned the Piankashaw in 1682 as one of the tribes gathered around his fort in the Illinois country. Chauvignerie classed the Piankashaw, Wea, and Pepicokia as one tribe but inhabited different villages. The Miami were divided into ten bands—wolf, loon, eagle, buzzard, panther, turkey, raccoon, snow, sun, and water—and the elk and crane were their principal totems.

Early in the 19th century, the Piankashaw and Wea were located in Missouri, and in 1832, they agreed to move to Kansas as one tribe. In about 1854, they were consolidated with the Peoria and Kaskaskia, and in 1868, the consolidated tribe was removed to a reservation on the Neosho River in northeastern Oklahoma. Numerous treaties were made between the main body of the Miami and the United States, and in November 1840, the last of the tribe was removed west of the Mississippi River. Six years later, some of them were in Linn County, Kansas, and others had confederated with the Peoria and other tribes. In 1873, they were removed to the Indian Territory.

The Sac and Fox, usually spoken of as one tribe, were originally two separate and distinct tribes, but both of Algonquian stock. The Sac (or Sauk), when first met by white men, inhabited the lower peninsula of Michigan and were known as “Yellow Earth People.” At that time, the Fox lived along the southern shore of Lake Superior and were called the “Red Earth People.” There is a tribal tradition that before the Sac became an independent people; they belonged to an Algonquian group composed of the Potawatomi, Fox, and Mascouten tribes. After the separation, the Sac and Fox moved northwest and, in 1720, were located near Green Bay, Wisconsin, but as two separate tribes. Trouble with the Fox led to a division of the Sac, one faction going to the Fox and the other to the Potawatomi. In 1733, some Fox, pursued by the French, took refuge at the Sac village near Green Bay, Wisconsin. Sieur de Villiers demanded the refugees’ surrender, but it was refused, and in trying to take them by force, several of the French were killed. Governor Beauharnois of Canada then ordered war on the Sac and Fox. This led to a close confederation of the two tribes, and since then, they have been known as the Sac and Fox.

There were numerous bands in the early days of the confederacy, but in time, these were reduced to 14. Black Hawk, the Sac War Chief, was a member of the thunder clan. After several treaties with the United States, the Sac and Fox, in 1837, ceded their lands in Iowa and were given a reservation in Franklin and Osage Counties of Kansas. In 1859, the Fox returned from a buffalo hunt to find that the Sac had made a treaty ceding the Kansas reservation to the United States in their absence.

The Fox chief refused to ratify the cession and, with some of his trusty followers, set out for Iowa, from which some of the Fox members had previously returned. They purchased a small tract of land near Tama City, Iowa, and later made more purchases until the tribe owned some 3,000 acres. From that time, this faction of the Fox had no further political connection with the Sac. In 1867, the Kansas reservation passed into the hands of the United States Government, the Indians accepted a reservation in the Indian Territory, and in 1889, they were allotted lands in severalty.

The Ioway were a southwestern Siouan tribe belonging to the Chiwere group, composed of the Ioway, Otoe, and Missouri tribes, all of which sprang from Winnebago stock, to which they were closely allied by language and tradition. Old Ioway chiefs said that the tribe separated from the Winnebago on Lake Michigan’s shores and, at the time of the separation, received the name “gray snow.”

Afterward, they lived on the Des Moines River, near the pipestone quarry in Minnesota, at the Platte River’s mouth, and at the Little Platte River’s headwaters in Missouri. In 1824, they ceded their lands in Missouri and, in 1836, moved to a reservation in the northeast corner of Kansas. When this reservation was ceded to the United States, the tribe moved to central Oklahoma, where, in 1890, they were allotted lands on several hundred acres.

The Kickapoo, a tribe of the central Algonquian group, was first mentioned in history about 1670 when Father Allouez found them living near the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers portage. Ethnologically, the Kickapoo were closely related to the Sac and Fox, with whom they entered a scheme to destroy Detroit in 1712. When the Illinois Confederacy was broken up in 1765, the Kickapoo was headquartered in Peoria, Illinois. They were allied with Shawnee Chief Tecumseh in his conspiracy early in the 19th century and, in 1832, took part in the Black Hawk War.

Five years later, they aided the government in the war with the Seminole. After ceding their lands in central Illinois, they moved to Missouri and later to Kansas, settling on a reservation near Fort Leavenworth. About 1852, several Kickapoo joined a party of Potawatomi and went to Texas. Later they went to Mexico and became known as the “Mexican Kickapoo.” In 1905, the Bureau of Ethnology reported 434 Kickapoo — 247 in Oklahoma and 167 in Kansas.

Among the Kickapoo, the gentile system prevailed, and marriage was outside of their bands. In summer, they lived in bark houses and in oval lodges constructed of reeds in winter. They practiced agriculture in a primitive way. Many fables of animals were characterized. In their mythology, the dog was especially venerated and regarded as an object of always offering acceptable to the great Manitou.

The Potawatomi belonged to the Algonquian group and were first encountered by white men near Green Bay, Wisconsin. They were originally associated with the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes, and the separation occurred around Lake Huron’s head. Subsequently, the three tribes formed a confederacy for offense or defense, and when they were removed west of the Mississippi River, they asked to be united again. They sided with the French until about 1760, participated in the Pontiac Conspiracy, and fought against the United States in the American Revolution. The Treaty of Greeneville ended hostilities, but in the War of 1812, they again allied themselves with the British.

Between 1836 and 1841, they were moved west of the Mississippi River, and those in Indiana had to be removed by force. Some escaped to Canada and lived on Walpole Island in the St. Clair River.

In 1846, all those in the United States were united on a reservation in Miami County, Kansas. In November 1861, this tract was ceded to the United States. The tribe accepted a reservation of 30 miles square near Horton, Jackson County, Kansas, where their reservation continues to stand today. According to government reports in 1908, about 2,500 Potawatomi were in the United States, 676 of whom were in Kansas.

The 15 bands of the tribe were the wolf, bear, beaver, elk, loon, eagle, sturgeon, carp, bald eagle, thunder, rabbit, crow, fox, turkey, and black hawk. The frog, tortoise, crab, and crane were their most popular totems. In the early days, they were sun worshipers. Dog flesh was highly prized when their special Manitou was selected, especially in the “feast of dreams.”

The Kiowa once inhabited the region on the upper Missouri and the Yellowstone Rivers. Next, they allied with the Crow but were driven southward by the Cheyenne and Arapaho to the country about the upper Arkansas and Canadian Rivers in Colorado and Oklahoma. Spanish explorers first mentioned them in history about 1732, and in 1805, Lewis and Clark found them living on the North Platte River. About 1840, they allied with the Comanche, with whom they were afterward frequently associated in raids on Texas and Mexico’s frontier settlements. In 1865, they joined with the Comanche in a treaty that ceded a large tract of land to the United States in Colorado, Texas, and southwest Kansas. Three years later, they were put on a reservation in northwest Texas and the western part of the Indian Territory.

The Quapaw, a southwestern tribe of the Siouan group, were separated from the other Siouan tribes when the Quapaw went down the Mississippi River, settling in Arkansas. In contrast, the Omaha group, including the Omaha, Kanza, Ponca, and Osage, went up the Missouri River. There is a close linguistic and ethnic relation between the Quapaw and the other four tribes, and their name derives from Ugakhpa, or “downstream people. When encountered by the French, they were described as having made considerable cultural advances, evidenced by their villages and structures.

The Quapaw were close allies of the French in colonial Louisiana, and during the later Spanish regime, they helped defend the colony from invasion by Indians allied with the English. The Quapaw tried to maintain a peaceful co-existence with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Still, they were forced to surrender their Arkansas lands to the U.S. government in 1818 and 1824. In 1833, old maps show that some of them lived on a small strip in southeastern Kansas, extending from the Missouri line to the Neosho River. In 1839, the Quapaw Reservation was established in Indian Indian Territory, which is currently utilized today. There are about 2,000 tribal members, most of whom live near Miami, Oklahoma.

The Otoe, one of the three Siouan tribes forming the Chiwere group, were originally part of the Winnebago, from whom they separated near Green Bay, Wisconsin. Moving southwest in quest of buffalo, the Otoe went up the Missouri River, crossed the Big Platte River, and, in 1673, lived on the upper Des Moines or upper Iowa River.

In 1804, Lewis and Clark found them on the south side of the Platte River, 30 miles from its mouth. Having become decimated by war and smallpox, they lived under the protection of the Pawnee. The Otoe were never an important tribe in Kansas history, though, in March 1881, they ceded to the United States a tract of land, a small portion of which lies north of Marysville in Marshall County.

By the New Echota, Georgia treaty, on December 29, 1835, the Cherokee Nation ceded the lands formerly occupied by the tribe east of the Mississippi River and received a reservation in southeastern Kansas. The tribe never assumed an important status in Kansas affairs, and in 1866, the land was ceded back to the United States. The Cherokee tribe was detached from the Iroquois at an early day and inhabited Tennessee, Georgia, southwestern Virginia, the Carolinas, and northeastern Alabama for at least three centuries. They were found by De Soto in the southern Alleghany region in 1540 and were among the most intelligent of Indian tribes.

Last but not least, the Indian tribes that dwelt in Kansas were the Wyandot, or Wyandot-Iroquois, who were the successors to the power of the ancient Hurons who originally lived on the northern shore of Lake Ontario. About the middle of the 18th century, the Huron Chief Orontony moved from the Detroit River to the lowlands of Sandusky Bay. Orontony hated the French and organized a movement to destroy their posts and settlements, but a Huron woman divulged the plan. The Handbook of the Bureau of Ethnology said: “After this trouble, the Huron seems to have returned to Detroit and Sandusky, where they became known as Wyandot and gradually acquired a paramount influence in the Ohio Valley and the lake region.”

In January 1838, several New York tribes were granted reservations in Kansas. Still, the vast majority refused to occupy the lands — only 32 Indians came from New York to the newly established Indian Territory. Some 10,000 acres were allotted to these 32 Indians in the northern part of Bourbon County. In 1857, the Tonawanda band of Seneca relinquished their claim to the Kansas reservations. In 1873, the government ordered all the lands sold to the whites, including the 10,000 acres in Bourbon County, because the Indians had failed to occupy them permanently.

During the French and Indian War, the tribe allied with the French; in the Revolutionary War, they fought with the British against the colonies. For a long time, the tribe stood at the head of a great Indian confederacy and was recognized by the United States government in making treaties in the old Northwest Territory. They claimed the greater part of Ohio, and the Shawnee and Delaware tribes settled there with Wyandot’s consent. In March 1842, they relinquished their title to Ohio and Michigan lands and agreed to move west of the Mississippi River. On December 14, 1843, they purchased 39 square miles of the Delaware Reserve’s east end in Kansas. There, they organized a Methodist church, a Free Masons’ lodge, a civil government, a code of written laws that provided for an elective council of chiefs, crime punishment, and social and public order maintenance.

Soon after the Wyandot came to Kansas, Congress made efforts to organize the Territory of Nebraska to include a large part of the Indian country. The Indians realized that if the territory was organized, they would have to sell their lands. Notwithstanding the government’s treaty promises, their possessions should never be disturbed, and their lands should never be incorporated into any state or territory. A congress of the Kansas tribes met at Fort Leavenworth in October 1848 and reorganized the old confederacy with the Wyandot at the head. At the Congress session in the winter of 1851-52, a petition asking for the organization of a territorial government was presented, but no action was taken. The people then decided to act for themselves, and on October 12, 1852, Abelard Guthrie was elected a delegate to Congress, although no territorial government existed west of Missouri. At a convention on July 26, 1853, which had been called in the interest of the central route of the proposed Pacific Railroad, a series of resolutions were adopted, which became the basis of a provisional territorial government with William Walker, a Wyandot Indian, as governor.

On January 31, 1855, tribal relations among the Wyandot were dissolved, and they became citizens of the United States. Simultaneously, the 39 sections purchased in 1843 were ceded to the government, with the understanding that a new survey was to be made and the lands conveyed to the Wyandot as individuals, the reserves to be permitted to locate on any government land west of Missouri and Iowa.

In the social organization of the Wyandot, four groups were recognized — the family, the gens, the phratry, and the tribe. A family consisted of all who occupied one lodge, at the head of which was a woman. The gens included all the blood relations in a given female line. When the tribe was removed to Kansas, it comprised eleven bands further divided into four groups.

Researcher James Mooney said the Wyandot were “the most influential tribe of the Ohio region, the keepers of the great wampum belt of union and the lighters of the council fire of the allied tribes.” But, like the other great tribes that once inhabited the central region of North America, the Wyandot have faded away before the civilization of the pale face. The wigwam has given way to the schoolhouse; the old trail has been supplanted by the railroad, and in a few generations more, the Indian will be little more than a memory.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated April 2024.

Also, See:

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Native American Photo Galleries

About the Article: The majority of this historic text was published in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. However, the text that appears on these pages is not verbatim, as additions, truncation, updates, and heavy editing have occurred.