One of the proposed solutions to the “Indian problem” was to create a separate homeland or territory for the indigenous people. By the 1820s, Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe had both proposed that the Eastern tribes should trade their ancestral lands for land west of the Mississippi River. They felt that to survive, the Native Americans must become “civilized” and learn the ways of the white man. The southern tribes had been moving toward “civilization” for years. They had developed prosperous farming societies. The Cherokee even had a written language and had declared themselves an independent nation by adopting the United States Constitution.

In 1829, Andrew Jackson became president. He felt the Native Americans did not have absolute title to the land and could not establish independent political sovereignty within the United States. On May 28, 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act. It authorized him to give land west of the Mississippi River to native tribes in exchange for their holdings in the East. The Removal Act only addressed the removal, not the exact locations or methods to be used.

The United States would “forever secure and guarantee” this land to them and their “heirs or successors,” provide compensation for the improvements upon their Eastern lands, and aid in their emigration to the West. President Jackson signed nearly 70 removal treaties into law. As a result, 46,000 Native Americans moved west, and as many more were under treaty to do so.

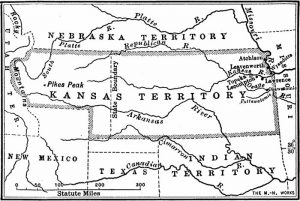

The territory began on the Red River east of the Mexican boundary and as far west as the country was habitable, then down the Red River eastwardly to Arkansas Territory, then northwardly along the line of Arkansas Territory to Missouri, then north along its westwardly line to the Missouri River; then up the Missouri River to Puncah River; then westwardly as far as the country was habitable; then southwardly to place of beginning. This gave a country 600 miles north and south and 200 miles east and west, as the country was not considered habitable over 200 miles west of the Missouri line because of the absence of timber.

These limits included the present State of Kansas, and from the passage of this Act for 24 years afterward, Kansas was a part of the Indian Territory. In this Act of 1830, the Indians were assured that these lands, which were given in exchange for those they were already occupying, should be theirs forever and that the United States would give them patents if they so desired.

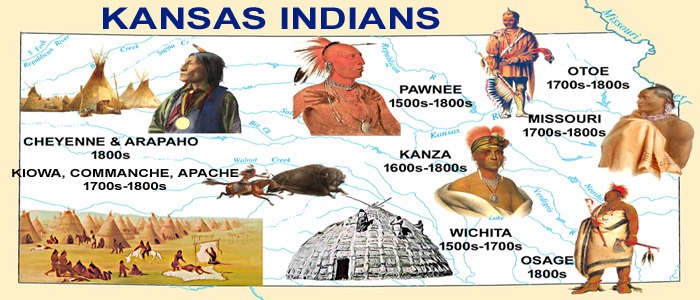

Kansas was originally occupied by four great Indian tribes, including the Osage, the Pawnee, the Kanza, and the Comanche, who claimed Kansas and extended widely beyond its present limits. They fought each other, disputed possession with the wild beasts, and were stricken down with fallen diseases, leaving behind mounds of earth, rings on the sod, fragments of pottery, and rude weapons and implements.

Previously, the Osage ceded nearly all their land in Missouri in 1808 and were located in Kansas by 1825. The Shawnee were removed to Kansas in the same year.

Due to the presence of the Indians, Fort Leavenworth was established as Cantonment Leavenworth in 1827 by a detachment of the Third United States Infantry and named in honor of Colonel Henry Leavenworth of that regiment.

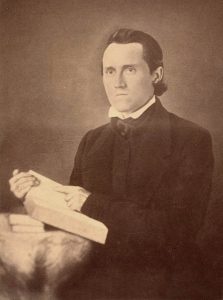

No name is to be written above that of Reverend Isaac McCoy on the missionary roll of honor. He began his work among the Miami in Indiana in 1817, continued it among the Potawatomi near Fort Wayne, Indiana, and followed that tribe to Michigan, where he also labored with Jotham Meeker and Dr. Johnston Lykins at the Ottawa Mission. Reverend McCoy effectively advocated the Act of 1830 to remove the Indians to the West. He preceded the Indians to Kansas and explored and surveyed their reservations. He was known to all the tribes. He firmly believed in the possibility of the elevation of the Indian and worked to that end for Mrs. Christina McCoy.

In 1831, the Delaware Indians came from the James Fork of the White River in Missouri and occupied their famous reserve in Kansas.

In 1832, the Cherokee and other southern tribes from Georgia and other states were removed to the Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, and the movement to fill the northern part of the Territory began. The Kanza Indians, whose name was later given to the State, once lived on the banks of the Missouri River, where Lewis and Clark saw the remains of their villages, but they were driven westward to the Blue River. The same year, the Kickapoo were removed from the Osage River in Missouri and moved to the neighborhood of Fort Leavenworth. The Cherokee were granted lands in Kansas, but it was never occupied. Several small tribes were granted lands in Kansas, including the Wea, Piankashaw, Ioway, Munsee, Peoria, Kaskaskia, and a small band of Chippewa.

The Intercourse Act of 1834 attempted to control the Indian removal. It gave a location for the Indian lands, “that part of the United States west of the Mississippi River, and not within the states of Missouri, Louisiana, or the Territory of Arkansas.”Due to the cultural acclimation of the Cherokee and other Southern tribes, the government tried to provide them with land that was acceptable to them. One incentive given was that the Indian Territory would have representation in Congress, which never came about.

Many of the tribes resisted, including the Cherokee and the Seminole, who had to be removed by force. The Cherokee suffered a forced march-the “Trail of Tears”- from Georgia to the Indian Territory. The U.S. Army estimates the number of Cherokee who died along the route at 1,000. Still, of the 15,000 involved in the entire removal process, 4,000 died in either the stockades awaiting removal, along the trail itself, or during the resettlement process. The Seminole tribe only complied after the U.S. Army fought two costly wars to get them out of Florida.

In 1836, the Ottawa were removed from Ohio and moved to their Kansas reservation, watered by the Marais des Cygnes River. The same year, the Sac and Fox were removed from Missouri and moved to the Kansas side of the river.

In 1837, the Pottawatomi began to gather in the Indian Territory.

While the Protestant missionaries established their centers, the Catholic missionaries established their principal headquarters at St. Mary’s, on the Kansas River, and then, missionary priests visited the different tribes while they remained. In Doniphan County, Reverend Samuel M. Irvin began a Presbyterian Mission among the Ioway in 1837, erected substantial buildings, and wrote a grammar of the Ioway language. A daughter of Missionary Irvin is believed to have been the first white girl born in Kansas; as a son of Missionary Thomas Johnson, Alexander S. Johnson was the first white boy. With Mr. Irvin, in the labor of the Mission, was associated Reverend William Hamilton.

The Wyandot attracted the good offices of the Friends as long ago as the date of their treaty with William Penn. Among the religious teachers of these people, Henry Harvey was honorably distinguished both in Ohio and Kansas. Perhaps the most ambitious attempt at mission building in Kansas, in the pre-territorial period, was the erection in 1839 of the Shawnee Mission Manual Labor School, two miles from Westport, Missouri. This was the work of Reverend Thomas Johnson, who, with his wife, had taught the Shawnee of the neighborhood since 1829. This mission became famous as the meeting place of the first Territorial Legislature, with Mr. Johnson serving as president of the first Territorial Council. Johnson County, Kansas, was named in his honor.

By the 1840s, most of the removal treaties had been implemented. But now westward expansion was accelerating, and settlers and traders were moving across land occupied by native tribes, first to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and then to Oregon. The concept of “Manifest Destiny,” control of land from shore to shore, led the United States to acquire the southwestern lands from Texas to California and the Oregon Territory.

Many of the removal treaties contained the provision that the United States would protect the relocated tribes from hostile whites and other native tribes indigenous to the area. As the removed tribes began to arrive, the white settlers in Missouri and Arkansas demanded protection from the relocated tribes.

In 1842, the Wyandot sold their lands in Ohio and were removed to the junction of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers. That year, Fort Scott was established for two purposes. One was to maintain peace between the native tribes and the white settlers by providing a military presence along the military road between Osage land and the state of Missouri. The other reason was to keep peace between the various native tribes.

At that time, Colonel Zachary Taylor favored temporary posts, General Winfield Scott favored building a few large posts, and Secretary of War John Bell wanted more numerous small forts. A compromise was reached, and a combination of large and small forts were manned, from Fort Snelling in Minnesota to Fort Jesup in Louisiana. Fort Scott fell right about in the middle of this line of forts.

The years 1846 and 1847 saw the relocation of the Miami of the Wabash Valley of Illinois and Indiana to present-day Miami County, Kansas.

By 1847, the Pottawatomi occupied 576,000 acres in the present-day Shawnee, Pottawatomie, Wabaunsee, and Jackson Counties. In 1850, Michigan Pottawatomi reinforced them here.

With the discovery of gold in California in 1848, thousands of people streamed through Indian Territory.

Fort Riley, the third important post in Kansas, was not established until 1853 and was named for General Bennett Riley, who guarded the Santa Fe Trail and fought in Mexico.

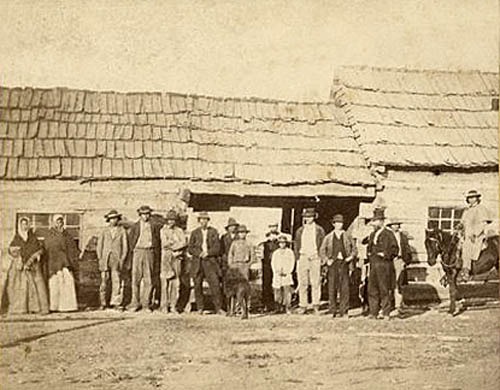

Between 1830 and 1854, the principal figures in Kansas were the regular army officer, the Indian trader, and the missionary. All these had important business with the Indians and seemed to have been kind to him. The Indian tribes residing in the Territory greatly differed in condition and character. The Wyandot, Shawnee, Delaware, and Ottawa were far advanced on the road to civilization. The Pottawatomi had long been neighbors of the white people; many bore French names and showed French blood. In Kansas, they divided, with those desiring to live as civilized people settling about the Missions and those who preferred the old ways going apart as the Prairie band. For all Kansas Indians, the government farmer plowed, the government blacksmith heated his forge, and the missionary preached in English and Indian, sang, prayed, printed, and taught.

By the 1850s, these factors, along with the desire for a transcontinental railroad and the establishment of Kansas as a territory, caused many of the forts of the “Permanent Indian Territory” to be abandoned. As white settlers moved into this land, the government’s policy of providing a large, permanent, and secure home for the Native Americans died.

The first Catholic baptisms of Kansas Indians were administered by Father Charles La Croix, who had labored with the Missouri Osage and who came to the Osage on the Neosho River in Kansas in 1822, where the Presbyterians had already established their Harmony Mission. They gave the Catholics a room for a chapel where several Osage children were baptized. Later, Father John Schoenmakers came to the Neosho River, along with several other missionaries and the Sisters of Loretto, and began what proved for him a lifetime of labor for the spiritual and temporal benefit of the Osage. Both these objectives were sought at all missions, Protestant and Catholic. At the Mission was also a sawmill, a grist mill, and a school.

There is no story of more utter devotion than that of Reverend Jotham Meeker, who was aided in all his labors by his wife. Meeker, called by the Indians “He that speaks good words,” labored first in Michigan with the Ottawa and Chippewa. He came to the Shawnee, in Indian Territory, in 1833 and later went to the Ottawa tribe in Franklin County, Kansas. He was a practical printer and brought the first printing press and type to Kansas. He printed the first book in Kansas and published an Indian newspaper and many books in the Ottawa language. Meeker, largely assisted by one of his converts, Mr. J.T. “Tawa” Jones, gathered a church and a school and opened a fine farm. After years of patient labor, Jotham Meeker died in 1854 and was followed in two years by his wife, and both rest where they fell in the cause of religion and civilization.

There were many names which should be kept in honor Chapman and Vinall, and Robert Simerwell and his wife; Francis Barker and Ira D. Blanchard, and Mrs. Webster and Miss Harriet H. Morse, and Reverend Moses Merrill and wife; the Hadleys, father and son; the Reverend E. T. Peery and Mrs. Peery; John G. Pratt, who was the printer of the Shawnee and Delaware; and of Father Gailland, long at the head of the Mission at St. Mary’s.

All these and many more labored for the Indians. They invented phonetic alphabets and created written languages. Father Gailland wrote a Pottawatomi dictionary; Father Hoeken published a Pottawatomi prayer book; and Father Ponzilione wrote an Osage prayer book. The first church-going bell that ever sounded in Kansas was a Mission bell. It was brought to the Baptist Mission near the present Mount Muncie Cemetery in Leavenworth and hung in the fork of a tree.

Following the Civil War, white encroachment and railroad speculation increased, and the Delaware were pressured to cede their lands in Kansas and relocate to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. In 1866, the U.S. government signed its final treaty with the Delaware Tribe, ending one of the longest ongoing treaty relationships between the federal government and an Indian tribe.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, April 2024.

Also See:

History of Native Americans in Kansas

Kansas and the Indian Frontier

Sources:

National Park Service

National Park Service – 2

Prentis, Noble Lovely; A History of Kansas, 1899.