By Henry Gannett in 1898

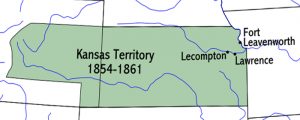

The Territory of Kansas was organized on May 30, 1854, after having formerly been under the jurisdiction of the Missouri Territory. Nearly all the region comprising the Territory was initially acquired by the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

In 1861, the Territory of Colorado was organized, taking from the Kansas Territory all that part that lay west of the 25th meridian. At the same time, on January 29, 1861, Kansas was admitted into the Union as a State with its present boundaries. In addition to the reduction in the formation of Colorado, Kansas was increased by the area in the southwest, which was taken from New Mexico. This addition was derived from territory admitted to the Union by the annexation of Texas and by the purchase of land from that State by the United States.

Although the settlement of Kansas was established mainly in the first half of the 19th Century, its exploration began much earlier. In 1541, Spanish Conquistador Vasquez de Coronado led an expedition from Mexico through New Mexico and across Kansas toward the northeast, searching for the mythical city of Quivira. His expedition, however, came and went, leaving no trace. In later years, settlement spread from New Mexico northward upon the plains of Colorado, but, so far as known, none reached the western or the southern boundary of Kansas, and there is no record of further attempts at exploration until the territory passed into the hands of the United States in 1803. Then commenced a series of explorations under the conduct of army officers, beginning with the famous expedition of Zebulon Pike in 1807 and ending with the Pacific Railroad explorations in the early 1850s. These expeditions traversed the region in all directions and, in an exploratory sense, made the area well known.

During the early movement to California, Kansas was traversed by a vast migration that largely followed two routes. One ran from Independence, Missouri, northwest across the northeastern corner of the State to Fort Kearny, Nebraska, and then up the Platte River. This would soon take on several names, including the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails. Starting from the same point, the second trail ran southwest to the Arkansas River, following it to Santa Fe, New Mexico. This, known as the Santa Fe Trail, traversed the entire breadth of Kansas from east to west. However, this vast migration across the state left few traces of settlement, for in 1855, the region contained 8,600 inhabitants. Five years later, the number exceeded 100,000 and rapidly increased until 1888, when it reached 1,518,552.

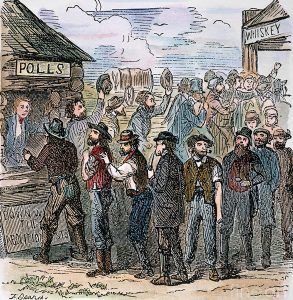

Voting in Kansas.

The State’s early settlement was affected by two factions: one primarily composed of immigrants from Missouri, who were determined to make it a slave State; the other, mainly from New England, equally determined that it should be a Free State. During the late years of its life as a Territory, the war between these factions was continuous and often bloody, and the struggle was terminated only by the election of the free-soil candidate for President in 1860. (See Bleeding Kansas)

After the state’s admission to the Union, its population and industrial growth were primarily dependent on the climate. Settlement commenced at the eastern end of the state and progressed westward. The eastern portion of the state is well-watered in ordinary years. On the other hand, rainfall was sufficient for agricultural needs in the western portion only in occasional years.

Rainfall shows a somewhat regular decrease from east to west across the State. Settlement, in its westward progress, encountered this deficiency of rainfall, but, encouraged by a succession of rainy seasons, it pushed forward in the early 1870s much beyond the safe limit of agriculture; this movement was efficiently aided and abetted by the railroad interests, which were concerned in disposing of their lands. Then followed a succession of dry seasons, and the settlers in middle Kansas were literally starved out.

In the next decade, forgetting this bitter experience and encouraged by a second succession of wet seasons, settlement again advanced. Indeed, by 1886 or 1887, it had reached the western boundary of the State. The inevitable again occurred in the form of a succession of dry seasons, and the western portion of the State was almost depopulated, with settlers suffering unprecedented hardships. In this second attempt to set the climate at naught, the results were vastly more disastrous than in the first since the number of people concerned was many times as marvelous. The entire state suffered seriously from the results. In subsequent years, nearly every county lost population, and the entire state lost nearly one-seventh of its inhabitants. A tremendous boom attended the rapid growth of Kansas between 1880 and 1887; land values rose enormously, not only in the rural portions but also in the cities. The following reaction and depreciation in values were disastrous to farmers and real estate speculators. However, a slight population increase in the mid-1890s indicated that Kansas was about to enter another period of prosperity.

The area of Kansas is 82,080 square miles. Broadly speaking, the surface is an undulating plain, rising gradually from an elevation of 700-800 feet at its eastern boundary to 3,000-4,000 feet at its western boundary. Most of the state’s surface conforms to the general characterization of an undulating plain, but erosion has cut it in certain places. On the east, the Missouri River flows in a broad bottomland, limited by bluffs 200 feet in height. Bluffs of considerable height also line the streams in the northeastern part of the state. In the southwest, many of the branches of the Cimarron River have cut courses that may almost be called gorges from their depth and abruptness. In the central-western portion of the state, considerable relief has been produced by stream erosion.

In the southwestern portion of the state, south of the Arkansas River, large areas are covered by drifting sand, which forms irregular hills. The sand is probably blown from the bed of the Arkansas River.

The state’s mean elevation is estimated at 2,000 feet. The distribution of rainfall ranges from about 40 inches near the southeastern corner to about 15 inches along the western boundary.

Agriculture depends not upon the mean rainfall for a term of years but upon the rainfall each year and is, therefore, practically controlled by the minimum rainfall. In rainfall, interannual variability is pronounced, especially in a sub-humid region such as most of Kansas.

The mean annual temperature of the State ranges from 52° to 58°, decreasing northward and increasing southward. The prevailing winds are from the northwest. Only a small proportion of the state is covered with timber, and it is only in the extreme eastern part that any areas are wooded, except in narrow belts closely confined to the streams. The trees are mainly broad-leaved species. Considerable progress has been made in the development of tree lines designed to serve as windbreaks. Trees have been cultivated successfully for this purpose, even as far west as the middle portion of the State. The species selected are commonly cottonwood, locust, and poplar.

Missouri River at White Cloud, Kansas by Kathy Alexander.

The slope of Kansas goes from west to east, and the course of the streams flows in the same direction. The state is drained by westward-flowing tributaries of the Mississippi River, the Missouri River, and the Arkansas River, as well as their branches. The Missouri River forms the northern part of the state’s eastern boundary. In its course along the border, it receives the waters of numerous small tributaries, and at Kansas City, the Kansas River, with its branches — Smoky Hill, Saline, Solomon, Republican, and Big Blue, drains the northern half of the State. The Osage River, commonly called the Marais des Cygnes in Kansas, drains a small area in the eastern part. In contrast, the Neosho River drains the southeastern corner and discharges to the Arkansas River. The Arkansas River, with its large tributary, the Cimarron River, drains most of the southern half of the State.

Kansas is primarily an agricultural State, so its manufacturing in the late 19th century was comparatively limited. However, their numbers were increasing rapidly. In 1880, the number of establishments was 2,803. By 1890, it had increased to 4,471. The principal articles of manufacture in 1890 were meat (the result of slaughtering and packing), flour, printing and publishing, foundry and machine-shop products, and men’s clothing.

At the same time, the state’s mining industry was primarily located in the eastern portion. Coal mining was carried out primarily in Crawford, Cherokee, Leavenworth, and Osage Counties, with 1/2 coming from Crawford County. The coal production in Kansas in 1896 was 2,884,801 short tons. Lead and zinc were also mined in the southeastern portion of the State, producing 20,759 tons in 1896. The zinc mines were located in Cherokee and Crawford Counties.

Politically, Kansas is divided into 105 counties, and their boundaries are determined mainly by township or section lines. The control of local affairs was divided between the township and county authorities.

In the late 19th Century, Kansas was well supplied with railroads, the total mileage being 9,025, an average of one mile of railroad to every nine square miles of territory. These railroads were in the hands of very few operating companies, numbering little more than a score. Two of these — the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, with 2,487 miles, and the Missouri Pacific, with 2,386 miles — operated more than half the mileage of the State. Other operators included the Union Pacific with 1,255 miles; the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific with 1,124 miles; the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas operated 383 miles; the St. Louis and San Francisco, 435; the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy, 260; the St. Joseph and Grand Island, 138; the Kansas City, Fort Scott and Memphis, 257; and the Wichita and Western, with 125 miles.

Kansas was also well-equipped with good wagon roads. The level surface ensured easy grades, and the soil’s character provided good dirt roads.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated December 2025.

By Henry Gannett; A Gazetteer of Kansas; Govt. Print. Office, 1898, Washington D.C. Note: Gannett’s article, as it appears here, is not verbatim as it has been truncated, updated, and edited.

Also See: