Salina, Kansas, the county seat of Saline County, was established in 1858.

In the spring of 1857, Colonel William A. Phillips traveled through the settled parts of Kansas and conceived the idea of making a foot tour through a portion of the unsettled territory to select a townsite. To accompany him on his tour, he engaged the services of an Englishman named Smith. From the vicinity of Fort Riley, Kansas, they started on foot, following the Smoky Hill River as far as the Saline River. They followed this course for a short distance before crossing the Solomon River. With their supplies becoming low, they made their way to Manhattan, renewed their stock of provisions, and started again, following up the Blue River until they came to the forks. Following the west branch of the Blue River, they came to the Military Road and turned onto it, following it until they reached Marysville. They struck out for Richmond from Marysville, a distance of 51 miles, which they accomplished in one day. Their journey lasted over two weeks, and they traveled an average of 40 miles each day. At that time, the first permanent settlement in Saline County was founded because after thoroughly examining the grounds over which he traveled for a townsite, Colonel Phillips determined to locate on the banks of the Smoky Hill River.

In February 1858, Colonel Phillips, in company with A.M. Campbell and James Muir, returned to the area and drove their stakes to locate a townsite they called Salina. Beautifully located, the site was in the center of a rich and fertile valley on the banks of the Smoky Hill River. It would be the first permanent settlement made in what would become Saline County. At that time, the region was officially an unorganized territory known as the Arapaho District. However, in February 1858, the Kansas Legislature passed a bill to organize and define five new counties west of the 6th principal meridian, including Saline County.

George Pickard brought the first stock of goods to Saline County in 1858. That year, the great floods washed away all the Government bridges on the Smoky Hill, Saline, and Solomon Rivers. On reaching the Solomon, Pickard found the bridge gone. To get his goods across the river, he had to construct a raft of wood and buffalo robes, on which he succeeded in getting them over, but in somewhat damaged condition. The washing out of the bridges necessitated laying a road on the south side of the river from Salina to Kansas City, which was challenging and arduous. Before starting for his stock of goods, which was not very large, Pickard had erected a small log house on the property that would later become the town of Salina. Here, he deposited his stock and opened it up for business.

In the meantime, having organized a Town Company, of which he was president, Colonel Phillips began to survey and plat the town in March 1858. This continued at intervals until March 1862, when it was finally completed. George Pickard had not been in the business for more than a few months when he sold out to Colonel Phillips, who increased the stock and established A.M. Campbell as a salesman. Several new settlers arrived almost immediately, most of whom were located in Salina or its immediate neighborhood.

On March 30, 1859, the town company was granted a charter by the Sixth Territorial Legislature of Kansas. That year saw a great stream of fortune seekers passing through Salina on their way to the newly discovered goldfields of Pike’s Peak in present-day Colorado. At that time, Salina was the westernmost station on the Smoky Hill Trail. Some on foot, some on horses, some on mules, some on ponies, some with hand-carts, and some were furnished with good teams and outfits. That year, Phillips built the first hotel in Salina, at the corner of Santa Fe and Iron Avenues, after hauling the pine lumber, doors, and windows from Kansas City. He later sold this building to H.L. Jones, who used it as a store and hotel. Mr. Jones took care of the store part of the business, while Mrs. Jones, highly qualified by education and training, managed the hotel. Also that year, Israel Markley built two or three houses. Phillips remained busy, erecting a sawmill, which was kept active, providing building materials. A county board of commissioners was soon created and met for the first time in April 1860.

When Kansas was admitted as a State in January 1861, the population of Saline County was less than 150 people, all of whom were located either in Salina or within a few miles of it. A few months later, the Civil War began, and immigration to the county virtually stopped. Later that year, the first post office was established in November 1861, with A.M. Campbell as Postmaster.

The first school was taught to area students as early as 1862, from a small frame house on Iron Avenue. That same year, the townspeople were thrown into a state of great alarm by well-founded reports that hostile Indians were approaching from the west, massacring all the white people they found. Some were inclined to pooh-pooh the idea, but when the ranchmen came to town after several had been butchered and confirmed the report, they discovered that it was a matter that required immediate action. The consternation became general, and a regular panic seized the community. Those who had settled east of Salina made for Junction City and Fort Riley, and those west and in the immediate neighborhood of Salina hurried to town. Seeing the danger that threatened them and knowing the terrible results of an Indian massacre, which was likely to occur, they immediately set to work. They built a stockade 50×150 feet on the north side of what is now Iron Avenue. These preparations were made none too soon; for the Indians, meeting with no opposition on their way, came on with a whoop; but seeing that the people of Salina were prepared to give them a warm reception, they gave the place a wide berth; and thus Salina escaped a massacre.

Confederate bushwhackers.

That same year, the fledgling settlement met with another foe — Confederate guerrillas. Early in the morning of September 17, 1862, while most of the townfolk were still in bed, they were awakened by a group of about 20 Confederate bushwhackers. So suddenly was the dash made into Salina, and so unexpectedly, that the people were unprepared to meet it, and from the very moment the gang entered, the town was at its mercy. Meeting with no resistance, they attempted no personal injury, but houses were entered, stores ransacked, and wherever any powder, ammunition, arms, or tobacco were found, the marauders appropriated them. They destroyed firearms they could not carry off with them, and everything was thought to be of service to the people in case of pursuit. On leaving, they took 25 horses and six mules, most of which were the property of the Kansas Stage Company. After they had gone, it was discovered that they had overlooked one horse, which was mounted by R. H. Bishop, who rode to Fort Riley, covering 50 miles in five hours. A party of soldiers was sent from the fort, but the bushwhackers had long gone. Although no one was hurt, it was a significant loss for the frontier community to lose its means of protection and transportation.

After the Civil War, Salina would get a boost when news that the Kansas Pacific Railroad would build its line through the town. With the arrival of the railroad came a stream of immigration, and Salina pushed forward rapidly. Before the advent of the railroad, there was neither a schoolhouse nor a church in the town, although there were several church organizations. Anticipating the railroad, which was then being pushed towards Salina as rapidly as possible, W. A. Phillips, in December 1866, surveyed and laid off lots in the new “Phillips’ Addition to Salina.”

Joseph G. McCoy, the alert livestock dealer who made Abilene the “Queen of the Cowtowns,” visited Salina in 1867, proposing that it become the terminus of the cattle drives. However, the few residents who lived there at the time feared that the “Texans” and their droves of “mossy horns” would disorganize their community, so the citizens rejected his offer. McCoy departed in a pique to Abilene, a dreary cluster of huts that he subsequently transformed into one of the great western “cow towns.” In commenting on Salina, McCoy declared it was “a very small dead place, consisting of about one dozen log huts, low, small, rude affairs, four-fifths of which were covered with dirt for roofing… The business of the burg was conducted in two small rooms, mere log huts.”

Joseph G. McCoy.

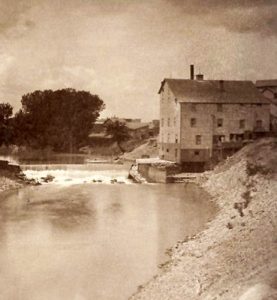

McCoy may have been correct then, but Salina’s condition would change quickly. That same year, the town’s first newspaper, the Salina Herald, was established by J.F. Hanna. Several other additions were made to the city, including a two-story frame schoolhouse on the corner of Santa Fe Avenue and Ash Street. With the Methodist Church being the first, churches soon followed, and a small frame building was built on Ash Street. That same year, C.R. Underwood built a grist mill on the Smoky Hill River, which was operated by steam and water power.

The development of Salina was greatly accelerated by the railroad after that. Josiah Copley, a correspondent for the Gazette of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, visited the settlement several months after Joseph G. McCoy and reported that the population had increased to almost 2,000. Large groups of settlers would soon begin to enter Saline County, including a colony of 60 Swedes from Galesburg, Illinois, who arrived in 1868; 200 homesteaders from Ohio came in 1869; and 75 ex-residents of Henry County, Illinois, arrived in 1870.

In 1868, mounted messengers came dashing into Salina with the alarming news that the Indians were upon the Republican River, perpetrating terrible deeds, outraging women, killing children, and murdering and scalping every white man they found. The people became greatly excited and telegraphed the facts to Governor Samuel Crawford at Topeka. The first train from Topeka west brought the Governor to Salina, where he instantly called for volunteers to go out to the scene of the troubles. A company of 60 men was quickly raised, and with the Governor in the lead, the men rode as far as Churchill in the southwest corner of Ottawa County. Learning there were no Indians between the Saline and the Solomon Rivers, they rode as far as Minneapolis, and from there, they pushed on to Delphos, on the northern boundary line of Ottawa County. They camped for the night at that point, and a party of six was sent out to scout as far north as Lake Sibley in Republic County. The next day, the scouting party, although seeing no Indians, came upon several dead bodies near Asherville — some men, some women, and some children. The men had all been scalped, the women outraged, and the children fastened to the ground with arrows. The dead were buried, and after performing this painful duty, the company returned to Salina, where it disbanded.

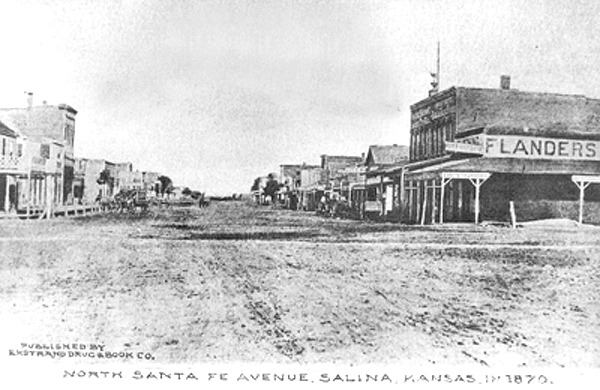

Salina, 1870.

In 1870, the people had previously voted to issue bonds to erect a courthouse, and a magnificent stone county building was built on the square. By the following year, Salina was one of the most flourishing towns in the state and featured several new buildings in its business district. But, on Christmas Day, much of its downtown district would be destroyed by a fire that originated in a saloon on the west side of Santa Fe Avenue and spread rapidly from building to building. Although several businessmen suffered substantial losses, the buildings that were erected afterward were built of materials other than wood. The following year, the Salina Journal was established by W.H. Johnson and M. D. Sampson.

Despite the inhabitants’ previous rejection of the cattle trade, Salina became a minor center of the industry in 1872. The businessmen expended a good deal of money to secure the trade derived from the town being made a trading point for cattle, but having secured it, the people soon discovered that it was not such a desirable thing after all. The trade-in itself was good enough, and the business of the merchants in town was significantly increased. However, the town became infested with such a crowd of disreputable characters, both male and female, that whatever advantage was gained in trade was more than counter-balanced by loss in morals. Though the people of Salina may have seen it that way, the rowdiness of Salina was mild compared to other Kansas cowtowns, as gunplay and carousing were sternly suppressed. In 1874, the cattle trade shifted farther west, and Salina’s citizens rejoiced that its “cowtowns” era was over. The resulting economic gap was more than made up for by agriculture. Great wheat crops began to pour into Salina during the 1870s. A $75,000 steam-powered flour mill was built in the town in 1878.

The year 1873 was one of rapid advancement, and many good residences were built, but the chief improvement that year was the construction of a large brick schoolhouse. However, for residents of the area and hundreds in western Kansas, 1874 would not be a good year. It would be a devastating year for many who depended upon the prairie and the crops they had planted. During the spring and early summer months, Kansas experienced sufficient rains, and the farmers eagerly looked forward to the harvest. But, during the heat of summer, a drought occurred. In late July, all of western Kansas was alarmed when, without warning, millions of grasshoppers, also known as Rocky Mountain locusts, descended on the Great Plains from North Dakota to Texas. Arriving in swarms so large that they blocked out the sun and sounded like a rainstorm, they ate the crops from the ground and the wool from live sheep. After ravaging the fields and trees, the locusts invaded buildings, clearing out barrels and cupboards and devouring anything not secured in wood or metal containers. They ate paper, tree bark, wooden tool handles, and even shredded curtains and clothing. The locusts were reported to be several inches deep on the ground, and at times, trains could not gain traction because the insects made the rails too slippery. Unfortunately for many Great Plains farmers, this devastation would continue for the next two years.

More money was expended on improvements in 1875 than in any previous year. If 1875 was a year of significant improvement, it was also one of some disaster. In that year, another disastrous fire visited the town, destroying a great deal of property. Several buildings on the west side of Santa Fe Avenue were wiped out, and a large livery stable, where 30 horses perished. This fire awakened the City Council and businessmen to the constant danger they were exposed to by having wooden buildings in the business district of the city. As a result, an ordinance was passed that prescribed fire limits and forbade the erection of any wooden buildings within those limits.

The city continued to grow with the grandest improvement made in 1877 — the erection of the Opera House, a magnificent three-story brick building on the southeast corner of Seventh Street and Iron Avenue. By the close of 1879, the business portion of the city was beginning to make an excellent appearance, with its numerous brick stores and large plate-glass windows. Meanwhile, the residential portion, especially in the southern part of town, was showing rapid improvement with several very fine residences. In 1882, the town was represented by two auction and commission houses, five dealers in agricultural implements, three in boots and shoes, two in books and stationery, four bakeries, three banks, one store, exclusively clothing, four drug stores, two furniture stores, seven general merchandise, ten groceries, six hotels, two the “Pacific” and “Metropolitan,” being superior and the others inferior, four hardware, three jewelry stores, and four restaurants. The manufacturers in the area are represented by two large flour mills and one smaller one, a bedspring and wire mattress factory, a carriage and wagon factory, a foundry, and agricultural implement works, as well as two cigar factories. There were six grain elevators in town, three lumber yards, two marble works, five blacksmith shops, four livery stables, and two wagon shops. There are also ten churches, a courthouse, an opera house, and two good school buildings. The press was represented by the Journal, Herald, and the Independent. The population was estimated at 3,500.

In 1903, a great flood affected the Missouri, Kansas, and lower Republican River Basins, as far west as Ellsworth, Kansas, damaging numerous river towns, including Salina. Salina received a significant amount of rain for the month, at 17.13 inches. By May 26, the water covered the north and west portions of the city, with rivers still rising.

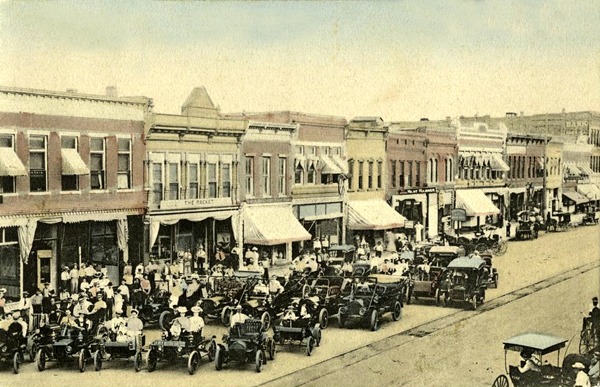

Salina, Santa Fe Avenue 1910.

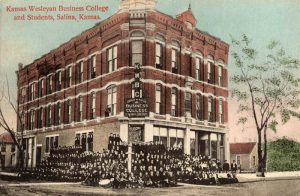

By the early 20th Century, Salina was one of the leading cities in Kansas, especially in manufacturing. By 1910, four railroad lines were coming and going from the city: the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific, the Missouri Pacific, the Union Pacific, and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, a hub of transportation for central Kansas. Among the manufacturing establishments of that time were flour mills, machine shops, cigar factories, an alfalfa mill, a vitrified brick plant, a planing mill, a glove factory, a foundry, a sunbonnet factory, creamery, carriage and wagon works, body brace factory, oil refinery, agricultural implement works, cold storage plant, razor strop factory, and broom and mattress factories.

The city also boasted two state and two national banks, six newspapers, a Carnegie library, and an opera house that could accommodate 3,000 people. The city also provided excellent grade schools and high schools, a hospital, and a training school for nurses, as well as four colleges: Salina Wesleyan, Salina Wesleyan Business College, Shelton’s School of Telegraphy, and St. John’s Military School. Its population in 1910 was 9,688.

With continued growth primarily in the wholesale and milling industries, Salina became the third-largest producer in the state and the sixth-largest in the nation. Salina’s population continued to grow through the decades and received another boost in 1943 when the U.S. Army established the Smoky Hill Army Airfield southwest of the city. The installation served as a base for strategic bomber units throughout World War II. When the war was over, it was renamed Smoky Hill Air Force Base in 1948, but closed just a year later. The closure was temporary, as it was reopened in 1951 as Schilling Air Force Base, as part of the Strategic Air Command. The reopening of the base triggered an economic boom in Salina, resulting in a 65% increase in the city’s population during the 1950s. However, in 1965, the Department of Defense closed the base permanently. The city of Salina subsequently acquired it and converted it into Salina Municipal Airport and an industrial park. The closure of the base resulted in a 12% decrease in the city’s population. Still, over the years, the airport and industrial park were developed, attracting companies such as Beechcraft and making manufacturing a primary driver of the local economy.

Located about 110 miles west of Topeka, Kansas, and just south of I-70, Salina continues to serve as a center for trade, transportation, and industry in north-central Kansas. Today, it has a population of nearly 46,500 residents and is still home to several colleges.

The old Saline County Courthouse in Salina, Kansas, now serves as a seniors’ residence, by Kathy Alexander.

Today, only a small percentage of the city’s historic buildings date from the 19th Century. However, as initially designed, the town’s layout is still apparent today, and all of the original townsite streets retain their original names. Instead, Salina’s historical appearance reflects its early 20th-century prosperity.

A visit to the Smoky Hill Museum, located at 211 W. Iron Avenue in Salina, provides visitors with a wealth of local history. The Museum’s collection features over 27,000 artifacts from the 1800s to the present, including agricultural implements, clothing from many different historical periods, furnishings, and more. The archival collection houses paper-based or two-dimensional artifacts such as books, Bibles, certificates, maps, and photographs. The Museum is housed in an Art Deco structure built as a Federal Post Office in 1938. Admission is free. 785-309-5776

More Information:

City of Salina

300 W. Ash Street

Salina, KS 67401

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated September 2025.

Also See:

Shilling Air Force Base, Salina, Kansas

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G.; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Federal Writer’s Project; Kansas, A Guide to the Sunflower State; Viking Press, New York, 1939.

Salina Historic Preservation Plan

Wikipedia