Wichita County Landscape, courtesy of Google Maps.

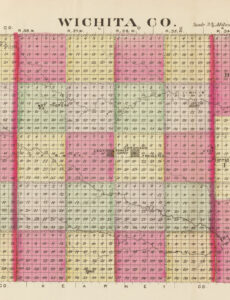

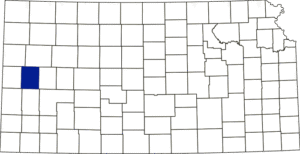

Wichita County, Kansas Location.

Towns & Places:

Leoti – County Seat

Marienthal – Unincorporated and Extinct

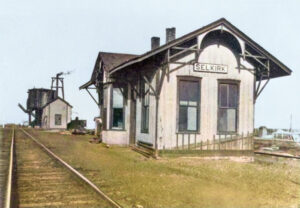

Selkirk – Unincorporated and Extinct

Wichita County, Kansas, is in the west-central part of the state, and its county seat is Leoti. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 2,152, and it has a total area of 719 square miles, virtually all of which is land.

It is the second county east of the Colorado line and the fourth south of Nebraska. It is bounded on the north by Wallace and Logan Counties; on the east by Scott; on the south by Kearny, and on the west by Greeley County.

The county was originally home to the Native American tribes of the Pawnee and the Wichita Indians, the latter of which is the tribe for which the county is named. However, they had already vacated the area before the first land cessions were made to the United States government.

The general surface of the county was an undulating prairie with bluffs along Ladder Creek. Bottom lands average a half mile in width and comprise 3% of the total area. Except for a few cottonwood trees that fringe the streams, there was no timber. Ladder Creek enters from the northwest and flows southeast and east into Scott County. Two branches of White Woman Creek cross the southern portion. Small quantities of chalk, gypsum, and building stone are found.

Wichita County was one of the last areas of Kansas to be settled because of its location, nearly 40 miles from both railroads: the Kansas Pacific Railroad and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. Only after other areas became overpopulated did settlers begin to move to Wichita County.

Wichita County was created in 1873. At that time, the area was largely uninhabited, except for Native Americans.

By 1880, the county had only 14 residents.

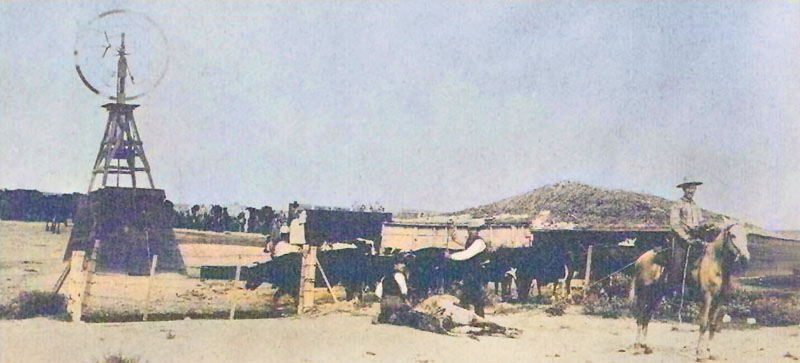

Prior to 1885, there were only seven dwellings in the county, all of which belonged to cattlemen. One of the largest cattle owners was George Edwards, who was the first white settler in the county.

The first signs of civilization in this county began with five large ranching operations: the Kitchen Ranch, the Sinn Ranch, the Russell Ranch, the Edwards Ranch, and the Holden Ranch. John Edwards, owner of Edwards Ranch, was one of the first settlers and was elected to be the first sheriff of the county.

Branding cattle in Wichita County, Kansas.

Once land was claimed and the recent rainfall had begun, people raced out to what appeared to be a high-quality agricultural area.

The plat for a townsite in Leoti was filed in 1885.

At about the same time, the town of Coronado was established.

Settlement was rapid during 1885 and 1886.

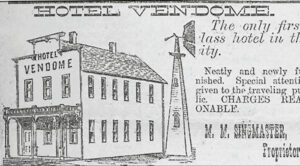

In 1886, the newly formed town of Coronado was abuzz with excitement as news of the railroad’s arrival in Western Kansas spread. On January 28, 1886, the first edition of the Coronado Star went to the press. New businesses were springing up fast. Soon, the little town had two hotels, a bank, several real estate and loan offices, a dry goods store, several hardware stores, a livery stable, two stagecoach lines, a millinery shop, and contractors and builders. Another newspaper, the Coronado Herald, soon started business. As Coronado continued to boom, new businesses arrived almost daily.

That year, the news broke that two railroads were actually coming. Before long, a depot, machine shops, a pump house, a well, and a water tank were all in place. The Coronado station was to be a division point.

By the spring of 1886, Coronado began to appear as a threat to Leoti for who would win the county seat. In under a year, Coronado had grown from a desolate area to a town with two hotels, two banks, hardware stores, a post office, and a bakery. Both towns had been established in 1885, but since Leoti had been founded first in the entire soon-to-be-county, and being geographically centered in the county, people from the surrounding area felt that Leoti should be the county seat. Coronado and Leoti were twin towns; Leoti had just barely beaten Coronado to the first land claim for a town.

Competition between these towns was fierce, not just among peers in the streets, but also in the newspapers. Editors of the newspapers would constantly accuse each other of lying, blasphemy, and even murder. Before the government established Leoti in June 1886, settlers began a fundraising campaign to send a Leoti delegate to the governor in Topeka to secure Leoti as the county seat of Wichita County.

In July 1886, the governor appointed W.D. Brainard to take the census. At that time, Leoti was the primary trading hub and had a larger population than any other town, making it a likely candidate to become the county seat. However, a group of professional speculators, some of whom had previously instigated contentious county-seat battles in other areas, set up operations in Coronado, a few miles east. They constructed impressive business blocks and began efforts to make their town the county seat.

Somehow, W.D. Brainard managed to delay submitting the census returns. On two separate occasions, he left Wichita County to report to the governor, but each time he went missing. Consequently, the census data and petitions did not reach Governor Alexander Martin until December. When they finally arrived, they were in such poor condition that the governor could not determine which town the residents preferred. He then appointed a commissioner to conduct an election to resolve the issue.

After Governor Martin believed the petition from Leoti to be “too irreconcilable,” he appointed his own commissioner in December 1886 to go to Wichita County and account for all of the households and citizens who were eligible to vote. Samuel Gerow was assigned to this job, which involved producing angry, trigger-happy men who would warn Coronado residents not to vote for their current town as the county seat. These threats against non-Leoti voters went so far as to involve teams guarding the county lines and “hidden” guards at the voting booths, but these men were clearly visible as they stood in nearby hotel windows and on balconies.

Two weeks after Gerow had arrived, he believed it was clear that Leoti was the better-suited county seat.

Voting took place in a sod shanty near Leoti, with each side demanding a thorough canvass. The voting process lasted three weeks, and tensions ran high; from the beginning, every man was armed. At times, as many as 200 armed men surrounded the polls, and it took considerable tact to avoid an outbreak of violence. The commissioner managed the situation well, but was relieved when the ordeal was over, and he could safely board the train.

On December 24, 1886, Leoti, having received a large majority of the votes, was made the temporary county seat. Lilburn Moore was appointed county clerk; R.E. Jenness, S.W. McCall, and W.D. Brainard, county commissioners. The census showed a population of 2,607, acquired in two years, of whom 1,095 were householders. The assessed valuation of the property was $510,572, of which $193,776 was real estate.

Another election was ordered for February 8, 1887, that would decide the final county seat between Leoti and Coronado. However, during the election, an estimated 400 residents from Coronado did not vote. Some residents in the two towns were furious at the immaturity of the non-voters, and demands for a re-election were almost immediate after the results were announced.

However, the governor approved a bill passed by the legislature that postponed all pending elections until March 10 to allow all voters to be registered.

So intense was the rivalry that one local person wrote:

“The people of the two towns love each other as his satanic majesty is said to love holy water.”

The tension was at its peak on February 27, 1887. On that day, the town of Coronado turned into a flash of bullets and gun smoke with casualties and a stream of blood running through the middle of town.

On that day, on an urgent invitation from supposed friends to Coronado, a number of Leoti young men drove over to that town to drink beer. Charles Coulter, William Rains, Frank Jenness, Albert N. Boorey, George Watkins, A. Johnston, and Emmet Demming, all residents of Leoti, left that place at 4:00 p.m. to socialize with some of the Coronado residents.

They met their friends in a drugstore, regaled themselves, visited for a while, and had gotten into their carriage to go home when someone called to them. Two of the Leoti boys got out of the vehicle, and some words were exchanged with a couple of Coronado young men who were on the sidewalk. Finally, a shot was fired, then a whole volley from people hidden in the second story of one of the buildings. William Rains and Charles Coulter of Leoti dropped dead. George T. Watkins was fatally shot, and Frank Jenness, A.R. Robinson, A.N. Boorey, and Emmett Denning were seriously wounded.

The wounded men got into their conveyance and went back to Leoti. Friends came after the bodies of the dead men and found them still lying in the street. Those under suspicion resisted arrest, and the governor was appealed to for help in maintaining order during the upcoming election. It was not found necessary to send the militia, but the governor appointed a commission to investigate the shooting. Eighteen men were arrested. It was found that more than 100 shots had taken effect upon the wagon, the horses, and the bodies of the Leoti men.

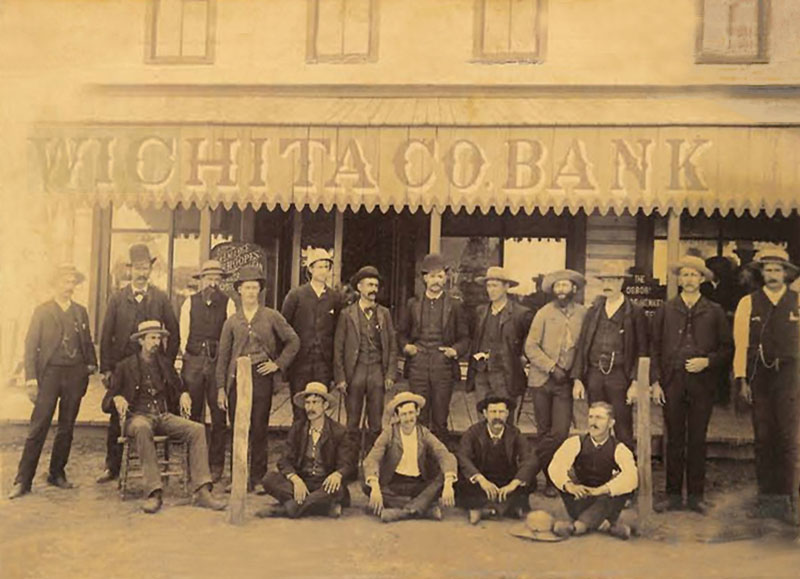

Soon, Coronado would find itself involved in one of the bloodiest county seat fights in the history of the American West. During its fight with Leoti, a shoot-out occurred on February 27, 1887, when men from nearby Leoti left several people dead and wounded. That unsettled period drew many outsiders to the county, with Leoti attracting “toughs” from Wallace County and Coronado drawing lawmen and gunfighters from the Dodge City area. Luke Short, Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson, Bill Tilghman, and others posed for the photograph that was taken in front of the Wichita County Bank in Coronado sometime that spring. Even though they were not involved in the actual gunfight, they were in Wichita County to intimidate at the voting polls.

Photographed before the Wichita County Bank in Coronado are standing left to right: Luke Short, Wyatt Earp, three unknown men, Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson, Bill Tilghman, Red Loomis, Jim Masterson, Pat, and Mike Sughrue.

On March 3, a report from Wallace, Kansas, stated:

“The situation in the Coronado-Leoti war remains unchanged. Both towns are surrounded by a strong cordon of armed men who permit no one to enter. The men in both towns sleep with their guns, and after gaining admission, a stranger finds a Winchester rifle at every turn. They stand in doorways, and merchants carry their guns while they wait for customers. Men patrol the streets of the town all day and night. The surrounding county is as excited as the towns, and the support is about equally divided. Coronado sympathizers are for the most part in town with their ammunition and guns, and the Coronado men said today that within an hour, 500 men could be recruited in the town, ready to defend it with their lives.

At Leoti, the cry is for revenge. The citizens are as excited as they were on the day following the shooting, and they are unanimous in their determination to sack Coronado at the first opportunity. This will likely be offered on Thursday night, coinciding with the county election.

Immediately after the shooting on Sunday, some men from Leoti came to Wallace and secured all the guns and ammunition they could get. Representatives from Coronado paid similar visits to Garage City, so that both towns are well-equipped with ammunition for war, which every man believes will occur before the matter is settled. The Leoti population, which their county cohorts have recruited, is looked to for the first move, and the Coronado men will be on the defensive. Each town has plans, but they are in such a chaotic state that predicting the probable outcome is impossible.”

Leoti was awarded the county seat on March 10, 1887, by Governor Martin after this historic county seat battle. The county officers met in the old Leoti Railway Depot. Being the county seat meant more business opportunities, and more business meant greater potential profit for residents. The feud between these towns was said to last for another year and a half; others claim it ended when another small town, Farmer City, died out after famous lawman Bill Tilghman shot Ed Prather. Prather was starting up what looked like another bloody battle in a desolate town that had no chance of surviving.

The Leoti-Coronado County Seat War was one of the bloodiest of the American West.

The county was divided into three townships: Edwards, Leoti, and White Woman.

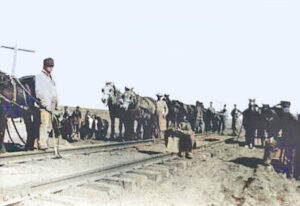

On July 28, 1887, the first steam locomotive arrived at Coronado. The Missouri Pacific Railroad was the first to finish its line. About a month later, the Chicago, Kansas & Western Railroad pulled in with their locomotive. People would board the train and ride to Scott City, the next county, to attend an afternoon baseball game. Riding the train became a social event.

The railroads continued their race on to Leoti, which was to be a stopping place to pick up passengers and freight at the depots. As they reached each town, the Leoti Standard reported, “there was great jolification and celebration.”

Next on the line was the little town of Selkirk, about ten miles west of Leoti and one and one-fourth miles east of the Wichita/Greeley County line. Again, the Chicago, Kansas & Western Railroad arrived in the town first, with the track completed on September 15, 1887, and the first regular train ran through to Selkirk on January 1, 1888. There was a large freight yard; the capacity at this point was not exceeded by any station on the line between Selkirk and Rush Center. It had a switch room for 12 cars more than at any point on the line.

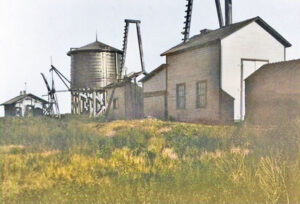

The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad was close behind. The Selkirk Graphic, a late-1800s newspaper, provided detailed coverage of the events surrounding the railroad. The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad had built a large depot with a ticket office, a telegraph office, an ample waiting room, a freight house, machine shops, seven acres of stockyards with double-loading chutes, a large wooden water tower, a pump house, and a hand-dug well.

By 1889, compared to its neighbor, Leoti was not as carefully architecturally engineered as Coronado. As a result of its recent win as the county seat, town planners were offering to buy buildings from Coronado and have them relocated to Leoti. Businessmen were also offering Coronado residents free lots within Leoti’s city limits. Soon, Coronado began to fade away.

In 1894, the farmers were in hard straits. Most of them had enough wheat for bread, but none for seed.

Eleven years after Wichita County was established, there were 1,500 people in it, according to the 1895 Kansas State Census.

A revival began in 1902, and by 1910, the population had grown to 2,006.

In 1910, there were post offices in Carwood, Leoti, Lydia, Marienthal, St. Theresa, Selkirk, and Sunnyside. The Missouri Pacific Railroad crossed the center of the county from east to west through Leoti, a distance of 30 miles.

At that time, barley was the leading field crop, which brought $70,000. Wheat was worth $42,801; sorghum, $40,000; and corn, $36,000. The total value of farm products that year was $327,193. There were 13,280 head of livestock, worth $521,685; the assessed valuation of property was $3,615,467, two-thirds of which was in farm lands.

The first and present courthouse was constructed from 1916 to 1917. Architect William Earl Hulse & Company of Hutchinson, Kansas, designed the Classical Revival-style two-story red brick-and-concrete structure. William Foley constructed it. Located on landscaped grounds in the center of Leoti, the building features a projecting center section with a large portico supported by four large, white columns. Behind the entrance are two large columns on either side. The north side has an entrance flanked by two high columns. In the interior, the County District Court courtroom is located on the south side of the second story. The building houses the County District Court of the 25th Judicial District. On the southeast side is the Public Library. It is located at 206 South 4th Street, Leoti.

Wichita County’s population peaked at 3,274 in 1970.

Today, visitors can step back in time and experience the Old West by strolling down Leoti’s pioneer Main Street at the Museum of the Great Plains. The museum, located at 201 North 4th Street, is home to an incredible display of old west artifacts, local cattle brands, Marion Bonner fossil finds, information on the Bloodiest County Seat Fight in Kansas, and much more. Additionally, the Museum of the Great Plains is home to the Wichita County Genealogy Society. A wealth of resources is available for you to research your ancestry. The research library is open on Tuesdays from 1:00 – 5:00 p.m. Step back in time and experience the Old West by strolling down Leoti’s pioneer Main Street at the Museum of the Great Plains. The museum, located at 201 North 4th Street, is home to an incredible display of old west artifacts, local cattle brands, Marion Bonner fossil finds, information on the Bloodiest County Seat Fight in Kansas, and much more.

Additionally, the Museum of the Great Plains is home to the Wichita County Genealogy Society. A wealth of resources is available for you to research your ancestry. The research library is open Tuesdays from 1:00 – 5:00 p.m.

Wichita County hosts the Wichita County Fair, featuring its famous community-owned-and-operated carnival, the last weekend in July. The four-day event is packed with food, fun, and entertainment. The 100+ year-old fair features 50¢ rides and games, as well as many long-standing traditions, including the parade, Old Settlers’ Breakfast, and rodeo. It is located at 800 East “M” Street.

Old well in Selkirk, Kansas, courtesy of Kansas Historic Resources Inventory.

In Sellkirk, visitors can peer down one of the country’s last remaining hand-dug wells. Constructed in 1887 for the “Great Bend Extension” on the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, it was intended to be part of the Santa Fe line to Denver, Colorado; however, the line was never completed and terminated in Selkirk. This rock-lined structure is the second-deepest hand-dug well in Kansas, measuring 102 feet in depth and 24 feet in diameter. It took 46 train carloads of stone, nine carloads of lumber for the curbing, and five carloads of cement. A total of 48,000 cubic feet of dirt was removed from the well. This dirt was hauled by train cars back to Ness City for stockpiling. It was used to lay railroad beds and similar structures. After the well was completed, the pump was installed in an above-ground pump house that transferred water to the large tank tower for use as needed.

The water from this hand-dug well had many uses. It was used to supply steam for the engines and to supply water for the stationary boilers, to wash train cars and floors, to clean out the boilers, to cool ashes, to provide fire protection, and to serve many similar purposes at the shops, engine house, and station buildings. The citizens of the town of Selkirk were also furnished with water at the cost only of the fuel necessary to run the apparatus.

The Missouri Pacific line ran parallel to the Santa Fe line between Scott City and Selkirk, forcing the Santa Fe line’s abandonment in 1896. In 1898, the Santa Fe line tracks were removed, thus ending the need for the well. At over 130 years old, the Selkirk Well is a fantastic specimen of railroad architecture. Also located on site are a railroad depot and a Santa Fe Railroad caboose.

There is no use for the railroad wells now; most of them have been filled in years ago. This well has been kept covered and in the same family’s ownership for about 70 years. It was donated to the Wichita County Historical Society for preservation. It was listed on the Kansas State Register of Historic Places in 2002.

Today, the county is served by the Leoti Unified School District 467.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated February 2026.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Wichita County

Sources:

American Courthouses

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Fort Hays State University

Gwin, Howard. A History of Wichita County, Kansas. MA Thesis. Kansas State College, 1954.

Harkness, Steve; The Great County Seat War: Coronado vs. Leoti Wichita County, Kansas 1885-1887, Chapman Center for Rural Studies, Spring, 2013.

Kansas Post Office History

Wichita County Museum

Wikipedia