Atchison County, Kansas.

Towns & Places:

Atchison – County Seat

Cummings – Unincorporated Semi-Ghost Town

Extinct Towns of Atchison County

Atchison State Fishing Lake & Wildlife Area

One-Room, Country, & Historic Schools of Atchison County

Border Ruffian Warfare in Atchison

Haunted Atchison – The Most Ghostly Town in Kansas

~~

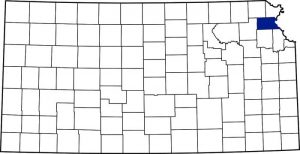

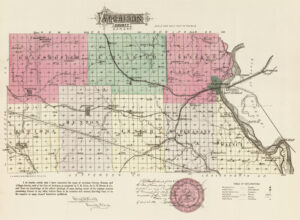

Situated on the Missouri River in northeastern Kansas, Atchison County was created by the first territorial legislature in 1855 and named in honor of David R. Atchison, a United States Senator from Missouri.

The first white men to visit the area were French fur traders who passed up the Missouri River during the first quarter of the 18th century. By 1764, French trade on the Missouri River was well established, and the eastern part of present-day Atchison County was well known to them.

Lewis and Clark followed the eastern boundary on their 1804 expedition and spent some time exploring the banks of the Missouri River. In 1818, the first military post established by the United States government in Kansas was built on Isle au Vache, also known as Cow Island. It was known as Cantonment Martin.

In 1833, the Kickapoo Indians entered into a treaty with the federal government, and the Kickapoo Reserve was established in most of the county, except for the southwest corner, which was part of the Delaware Reserve, established by a treaty in 1831.

In 1833, the Methodist Episcopal Church established a mission among the Kickapoo Tribe in what is now the northwestern corner of the county near Kennekuk. The first white man to permanently locate and erect a home was a French trader named Paschal Pensoneau, who married a Kickapoo Indian and settled on the banks of Stranger Creek in 1839. Later, however, the Indians were forced to cede their lands to the federal government, and in 1854, the land was opened to settlement.

As soon as it was known that the Kansas Territory would be opened to settlement, a pro-slavery party in Missouri began to make plans to settle the area with other like-minded individuals. Some of the first settlers were a party from Iatan, Missouri, who took claims near Oak Mills in June 1854. However, the settlers and founders of the county and city of Atchison did not enter the territory until the next month. Some of the first settlers of Atchison County in 1854 were James T. Darnall, Thomas Duncan, Robert Kelly, B. F. Wilson, Henry Cline, and Archibald Elliott. At this time, the friction between Free-State advocates and pro-slavery supporters was significant. The champions of slavery determined to make Atchison County their own, in opposition to Lawrence, the Free-State champion, in nearby Douglas County.

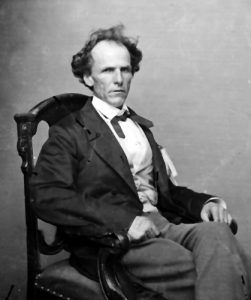

In July 1854, the town of Atchison was founded by pro-slavery settlers and named for David R. Atchison, who was then President of the Senate and acting Vice-President of the United States. He was also an ardent advocate of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, a champion of Popular Sovereignty and the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, and a resident of Missouri. As he looked across the broad Missouri River, he saw many opportunities, including rich farmland, commercial opportunities along the river, and a broad domain that could positively influence his political party.

Senator Atchison selected the site of the new town because it was on the direct route to New Mexico and California and was already a favorite stopping place for weary emigrants bound for those far-off regions.

The outfitting points for the immense traffic on the California, Oregon, Mormon, and Santa Fe Trails prior to 1854 were at Independence, Weston, and Westport, Missouri. Senator Atchison saw an excellent opportunity for a new town in Kansas to become a new jumping-off point for the many pioneers heading westward.

Soon, the town of Atchison was founded by several men, including Dr. John H. Stringfellow, Ira Norris, Leonidas Oldham, James B. Martin, and Neal Owens. All of them, except for Dr. Stringfellow, had taken claims in Walnut Creek Valley, four miles west of Atchison.

One of the earliest and, practically, the only Free-State settlement in what would become Atchison County was established in October 1854 by Caleb May. The town, located in Center Township, was called Pardee.

When the county was created by an act of the first territorial legislature in 1855, county commissioners were appointed, and Atchison was made the new temporary county seat. Townships were soon surveyed, and other county officials were appointed shortly thereafter. The Atchison Town Company donated a block for the site of a county courthouse.

Though thousands of people passed through Atchison County along the well-known trails, few settlers weren’t from Missouri. These pro-slavery advocates so predominated that the people who supported Free-State principles did not dare let it be known. The first open trouble between a Free-State man and the pro-slavery men in Atchison County occurred in 1855, when J.W.B. Kelley, a free-soiler in politics, made offensive remarks about slavery, particularly about a female slave who was supposed to have committed suicide.

As a result, her owner attacked Kelley. Many of the town’s citizens adopted resolutions ordering Kelley to leave the town under penalty of further punishment. They also ordered all emissaries of the abolition societies to leave, or face “the hemp.” It was resolved to “purge” the county of all Free-State people, and all persons who refused to sign the resolutions were to be regarded and treated as abolitionists.

The bold attitude of the Free-State settlers of Lawrence further stoked political feeling among the pro-slavery men of Atchison. During the Wakarusa War, part of the Bleeding Kansas violence, November and December 1855 saw an Atchison company take a prominent part in the siege. The following year, other companies fought in the Battle of Hickory Point in September 1856.

The pro-slavery leaders of Atchison, who dominated the county’s politics, had so terrorized the other settlers that up to the summer of 1857, the Free-State men in the county had formed no organization. Meetings had been held outside of Atchison; however, a society was formed at Monrovia during the summer, which had been established the previous year in Atchison County. At about the same time, the Atchison Town Company disposed of a large part of its property interests to the New England Aid Company. The Squatter Sovereign, the county’s first and a strong pro-slavery newspaper, was turned over to Samuel Pomeroy. With F. G. Adams and Robert McBratney, he turned it into the Champion, a Free-State newspaper.

As the town company had made such a compromise in politics for the sake of business, F.G. Adams thought that the Free-State men could go still further and advertised that General James H. Lane would speak in Atchison in October 1857. Several reliable Free-State men came from Leavenworth to see fair play, as the opposition declared that Lane should not speak. On the morning of October 19th, Adams was assaulted, and feelings ran so high with both parties parading the streets armed that it was decided to postpone the meeting. Lane was turned back before entering the city, thus avoiding further trouble.

In 1857, several more towns were established in Atchison County, including Lancaster, Pardee, and Mount Pleasant. In Atchison, the Benedictines established St. Benedict’s Abbey in 1858, and Mount St. Scholastica was built in 1863. The Benedictine Brothers and Sisters have played an integral role in the community’s cultural, religious, and educational development for nearly 150 years.

There was some question about the permanent location of the county seat. This was not settled until the October 1858 election, when Atchison received a majority of the votes and became the permanent county seat. The county courthouse and jail were completed in 1859.

Atchison County was the first county in Kansas to secure railroad connections when the St. Joseph & Atchison road was completed in February 1860. This was most important for the county and city of Atchison, as it removed much of the trade that had formerly gone there from Leavenworth and secured the shipment of all the government freight to the western military posts. It also removed the starting point of the overland mail to Atchison from St. Joseph, Missouri.

In the end, the early efforts of the pro-slavery men in Atchison County were in vain. Kansas became a free state in 1861. The call came for volunteers when the Civil War began that same year. Despite its early population of pro-slavery men, the county was well represented in the Union forces. Being on the border, Atchison County also found itself the target of raids from the Confederate army and guerrilla bands from across the border, which necessitated raising companies of home guards. By 1863, the depredations of lawless bands became so annoying that vigilante committees were formed, the members taking an oath to support the Union and to assist in suppressing the rebellion. They became effective auxiliaries to the civil authorities in enforcing the law.

After the Civil War, the county continued to grow and prosper. But this was not the case for everyone, and the county created a “Poor Farm” in 1869. The boom years for Atchison County began in the early 1870s, as several major industries were developed, including the development of one of the state’s first major banking centers. John Seaton’s foundry was moved to Atchison in 1872 and occupied an entire block. It was the largest manufacturer west of St. Louis, Missouri, and would eventually employ about 2,000 men. During this decade, only two cities in Kansas – Leavenworth and Topeka – were more critical to manufacturing than Atchison.

By the 1880s, the county was bustling with railroads and riverboat traffic, and its towns were filled with busy stores and comfortable homes. As business grew, the old courthouse became too crowded, so a new one was erected in the winter of 1896-97.

Near the beginning of the 20th century, the Topeka Mail & Breeze described Atchison as having more rich men and widows per capita than any other city in Kansas. These wealthy citizens built scores of grand mansions, many of which still stand today.

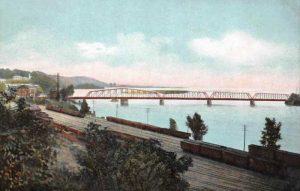

However, the county had made a fatal mistake when it delayed construction of a bridge over the Missouri River several years earlier. Not building a bridge until 1875, ten years after St. Joseph and Kansas City, Missouri, eventually took their toll on the thriving town of Atchison, from which it would never recover.

The historic railroad depot in Atchison, Kansas, now serves as a museum and information center, by Kathy Alexander.

The county’s population peaked in 1900 at 28,606 people. Over the next century, the county would lose more than 10,000 residents as farms consolidated and many manufacturing facilities closed or moved elsewhere.

In 1958, Atchison suffered two flash floods that swept through downtown, earning the city the nickname “the city that refused to die.” Its residents rebuilt many of the oldest commercial buildings, eventually leading to the construction of the pedestrian mall, which today is the heart of the downtown district.

Though not the booming place it once was, Atchison County continues to display its rich history in museums and numerous Victorian mansions. The city of Atchison boasts more than 20 sites on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, the county’s population is about 16,380 and comprises five rural communities, including Atchison, Effingham, Huron, Lancaster, and Muscotah, as well as a couple of other very tiny unincorporated villages.

A visitor center is located in the Santa Fe Depot in Atchison. It provides brochures on nearly every community along the Kansas-Missouri border, Kansas Travel Guides, publications on Wildlife and parks, and maps.

More Information:

Atchison County Chamber of Commerce

200 South Tenth

PO Box 126

Atchison, Kansas 66002

913-367-2427 or 800-234-1854

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated December 2025.

Also See:

Haunted Atchison – The Most Ghostly Town in Kansas

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas Cyclopedia, Standard Publishing, 1912

Cutler, William G.; History of the State of Kansas, A. T. Andreas, 1883

Ingalls, Sheffield; History of Atchison County, Kansas, Standard Publishing Company, 1916

Kansas Towns

Newsleaf Museum