Westward Expansion.

Westward expansion of the United States by settlers is as old as the nation itself. The European settlers who came to America in search of a new life believed that land acquisition was crucial to their future prosperity.

Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 from France and the subsequent exploration of that western territory by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the nation’s appetite for expansion grew. The Louisiana Purchase, which nearly tripled the size of the young country, effectively set off a chain reaction for U.S. territorial expansion. The following 50 years of American history saw the nation’s land holdings increase exponentially.

Beginning in the 1820s, the area that would become Kansas was designated as Indian territory by the U.S. government

In 1821, the Santa Fe Trail was opened across Kansas as the country’s transportation route to the American Southwest, connecting Missouri with the well-established Santa Fe, New Mexico. Due to the burgeoning trade, the United States Army established posts throughout the region.

By treaty dated June 3, 1825, the Kanza Nation ceded 20 million acres of land to the United States, and the Kanza tribe was subsequently restricted to a specific reservation in northeast Kansas. In the same month, the Osage Nation was limited to a reservation in southeast Kansas.

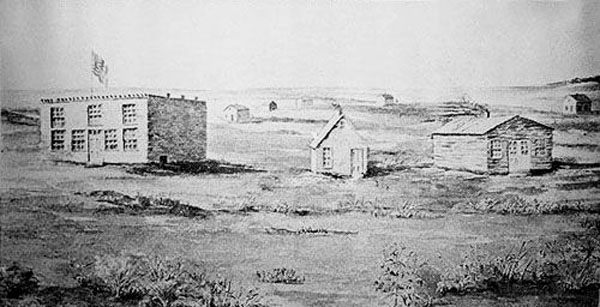

In 1827, Fort Leavenworth was built to protect travelers.

The settlement of Kansas between 1830 and 1890 involved the relocation of thousands of American Indian tribes from the East and Great Lakes regions to the area. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 resulted in the removal of more than 10,000 American Indians to what is now Kansas, which was closed to white settlement.

The Kickapoo, originally from Wisconsin, were removed to Kansas from Missouri in 1832. In 1836, the Ioway from north of the Great Lakes were assigned a reservation in Kansas. In 1838, the Potawatomi began their move from northern Indiana. Treaties with the Sac and Fox of the Mississippi Valley from 1842 to 1861 ceded Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska lands to the United States, leaving small reserves in Doniphan and Osage Counties. The Miami were moved by barge from Indiana in 1846.

A section of the Santa Fe Trail, which ran through Kansas, was also used by emigrants on the Oregon Trail, which opened in 1841.

Manifest Destiny, the idea that God wanted Americans to move westward and expand across the entire continent, was coined by magazine editor John L. O’Sullivan in 1845 and inspired settlers of all backgrounds.

Despite the extensive plans that were made to settle Native Americans in Kansas, by 1850, white Americans were illegally squatting on their land and clamoring for the entire area to be opened for settlement.

Presaging events that were soon to come, several U.S. Army forts, including Fort Riley, were soon established to guard travelers on the various Western trails.

Congress began the process of creating the Kansas Territory in 1852. Southern Senators stalled the progression of the bill in the Senate while the implications of slavery and the Missouri Compromise were debated. A heated debate over the bill would continue for a year before eventually resulting in the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which became law on May 30, 1854, establishing the Nebraska Territory and the Kansas Territory.

Meanwhile, by the summer of 1853, it was clear that eastern Kansas would soon be opened to American settlers. Nearly all the tribes in the eastern part of the Territory ceded the greater part of their lands prior to the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. They were eventually relocated south to the future state of Oklahoma. The final step in Americanizing the Indians was taking land from tribal control and assigning it to individual Indian households, to buy and sell as European Americans would. For example, in 1854, the Chippewa inhabited 8,320 acres in Franklin County; however, by 1859, the tract had been transferred to individual Chippewa families.

In 1854, the newly created Territory of Kansas was opened for white settlement. Some settlers began arriving in Kansas as early as April 1854, and their numbers continued to increase thereafter.

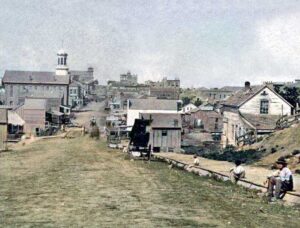

Leavenworth was the first town in Kansas. It also played a significant role in the history of the Territory. It was located on land adjoining the Fort Leavenworth reserve on the south. One of the best locations in the Territory, it enjoyed communication by steamboats on the Missouri River, and there was much business at the Fort, which gave it a great advantage.

It was laid out by an association formed at Weston, Missouri, on June 13, 1854. By August 1, there were a good many settlers on the townsite. The first settlers were primarily from Missouri, but at the time of the first sale of lots on October 9 and 10, settlers were also arriving from Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. The city of Leavenworth became a rival to Atchison as a hotbed of pro-slavery sentiment and operations. Some of the first disturbances in the Territory were at Leavenworth. Among the Missouri settlers were many Free-State men, as in the settlements of Atchison.

Two of the early settlements became most notable in the history of the Territory and the State. These were Lawrence and Atchison. Lawrence was founded in what was later made Douglas County, and Atchison was laid out in what became Atchison County. However, when the first settlements were made, no counties had been formed, and these towns had not been located.

The first arrivals, in what became Douglas County, were probably pro-slavery men, although Free State men began to arrive early in June. The Oregon Trail, locally known as the California Road, passed through the northern part of the county. This trail crossed the Wakarusa River at the house of Charles Blue-Jacket, a Shawnee Chief. The pro-slavery settlers established the town of Franklin on the California Road, about two miles west of the crossing. The trail passed up Mount Oread and followed the “backbone ridge,” which divided the waters of the Kansas River from those of the Wakarusa. Six miles west of Mount Oread, on a fine elevation, there was a noted spring. At that point, Judge John A. Wakefield, who arrived in the Territory on June 8, 1854, made his home. Another notable place on the trail was Big Springs, located within a mile of the western county line, where another settlement was made.

The site of the city of Lawrence was selected in July 1854 by Charles H. Branscomb and Dr. Charles Robinson of Massachusetts. They visited the Territory as agents of the New England Emigrant Aid Company. After surveying the country, they chose the site of Lawrence as the point where the Aid Company would make its first settlement.

The first colony sent out by the Emigrant Aid Company left Boston, Massachusetts, on July 17, 1854, and arrived at Kansas City on July 28. It consisted of 29 men. They reached the site selected for their settlement on August 1. On that day, the hill on which the University of Kansas now stands was named Mount Oread, for Oread Seminary of Worcester, Massachusetts, founded by Eli Thayer. Fifteen of this party remained on the selected site, while the others secured claims some distance away. Charles H. Branscomb was the leader of the first party.

The second party sent out by the Emigrant Aid Company left Worcester on August 29, 1854, and consisted of 67 people. There were ten women and a dozen children at this party. Dr. Charles Robinson and Samuel C. Pomeroy led this party.

The third party of Aid Company emigrants, led by Mr. Branscomb, arrived in Lawrence on October 8 and 9. Most of these became disgusted with the outlook and immediately returned. They exhausted their vocabulary, denouncing Mr. Thayer and his agents, claiming that they had been deceived. They were probably poor material for pioneers. The Emigrant Aid Company sent out two other companies during the year.

Lawrence, the headquarters of the Free-State men in Kansas, played a leading role in Kansas Territorial history. The capital of the Kansas Territory, Lecompton, was also in Douglas County. The old Santa Fe Trail passed through the southern part of the county, and a number of ambitious towns were formed along that famous highway. Among them were Palmyra, Louisiana, and Brooklyn. Prairie City was only two miles south of it, and Baldwin City was about one mile south. The post office of Hickory Point had been fixed on the site of Louisiana before the town was laid out. Hickory Point gained notoriety later as the site where some of the events leading up to the Wakarusa War took place.

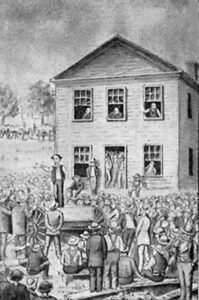

Atchison was the stronghold and headquarters of the men determined to make Kansas a slave state. From that town, many of the operations of the pro-slavery forces were directed. The town was laid out by residents of Platte County, Missouri, and named for Senator David R. Atchison, who spent a considerable part of his time there but never made it his legal residence.

The first settlers began to arrive in Atchison County in June 1854. They staked out claims near where Oak Mills would later be located. They did not erect dwellings then. The first houses were built on claims filed in July 1854. Senator Atchison had decided that a city should be built in the Territory at the Big Bend of the Missouri River, and on July 20, Dr. John H. Stringfellow, Ira Norris, Leonidas Oldham, James B. Martin, and Neal Owens left Platte City, Missouri, to make the definitive location. They selected the site, a company was formed, and the town was laid out. In a speech on the morning the sale of lots began, Senator Atchison reviewed the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. He also touched upon the future of the Kansas Territory, saying that if he had his way, he would hang every abolitionist who dared show his face there. He qualified his words to prove to his hearers that he had no prejudice against the Northern settlers, saying that he knew there were sensible, honest, right-feeling men among them who would be as far from stealing a negro as a Southern man. Senator Atchison was known all over the South, and his connection with the town of Atchison caused the rabid slavery men coming into the territory to select that city for their residence. The country’s settlement about Atchison was made in the same manner and at the same time as other settlements of that day. Among them were many Free-State men. Many Missourians settled in the country who acted with the pro-slavery men through the fear that their lives and property would be in danger if they did otherwise. They were, in fact, opposed to slavery, and were pleased when Kansas was made a free state.

Topeka was founded on December 5, 1854, by Cyrus K. Holliday, a native of Pennsylvania. It was designed by Holliday to be the capital of Kansas. The Free-State men, when they established an opposition government, made it their capital in the Kansas Territory. Later, it became the capital of the State.

The settlers coming from free states did not, as a general thing, stop on the border. They moved up the Kansas River and other streams, 40 to 50 miles, to stake out their claims. They hoped to avoid trouble by doing so. They intended to make their settlements where they would be unmolested by the pro-slavery settlers from Missouri as far as possible.

The eastern border of Kansas, generally, was settled in about the same manner and near the same time that these settlements already noted were formed. The rules established by the settlers in these early communities were reflected mainly in all subsequent settlements in the Territory. These squatter associations were compelled to make rules for regulating the conduct of the various communities, and it will be seen that there was little friction between the early settlers until after the enactment of laws by a regularly constituted legislature.

The first newspaper to be published in the Territory was the Kansas Weekly Herald, the first number of which appeared on September 15, 1854. It was a pro-slavery paper.

The first Free-State newspaper in the Territory was the Kansas Free State. The first issue was dated January 3, 1855. It was owned and edited by Josiah Miller and R.G. Elliott. Mr. Miller was a native of South Carolina but was a Free-State man. The first number of the paper had this to say: “We are uncompromisingly opposed to the introduction of slavery into Kansas, as tending to impoverish the soil, to stifle all energy and enterprise, to paralyze the hand of industry and to weaken intellectual effort.” Having been reared in a slave state, he could state his objections to slavery in this succinct form.

With the pro-slavery and Free-State forces fighting against each other, both sides drew up constitutions, neither of which was acceptable to the United States Congress. Finally, in 1859, the Free-State Wyandotte Constitution was approved. This cleared the way for Kansas to achieve statehood on January 29, 1861, just as many southern states were seceding from the Union. Kansas was the thirty-fourth state admitted to the Union.

Swedish pioneers who moved to central Kansas in the mid-1800s called their new home “framtidslandet,” the land of the future. Many left Sweden when famine threatened starvation. The Swedish immigrants, in turn, encouraged their friends and family to join them.

Children without parents to care for them were given special help to come to Kansas. Some of these children were recent immigrants from Europe; others were abandoned or homeless American children. The Children’s Aid Society of New York operated orphan trains between 1854 and 1929. Of the 150,000 children who left New York, nearly 5,000 of them were adopted by families in Kansas.

It was not until after the Civil War, however, that Kansas experienced a significant population increase.

In 1862, Congress passed the Pacific Railway Act and the Homestead Act, which vastly accelerated westward expansion and encouraged many settlers to move to Kansas. The Pacific Railway Act authorized the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific Railroad companies to construct a transcontinental railroad. The Act would result in the construction of four transcontinental railroads and the allocation of 174 million acres of public land to the companies, aimed at encouraging the growth of a national railroad system.

The Homestead Act allowed settlers, citizens, or immigrants to claim 160 acres of public land. Claimants who resided on and improved the land for five years would then receive title to the land. Homesteaders also had the option to buy the land for $1.25 an acre, after living on and improving it for six months. In fact, most acreage under the Homestead Act was given to land speculators, ranchers, miners, lumbermen, and railroad companies. While the Pacific Railway Act and the Homestead Act contributed to the settlement of Kansas, settlement was mainly the result of railroad companies selling smaller pieces of land to homesteaders. Three groups of settlers — white Americans, African American “exodusters,” and European immigrants — moved to Kansas from the 1850s through the 1880s, following these and other government actions. Over 70% of the immigrants arriving in these years were engaged in agricultural pursuits. Agriculture remained the principal occupation for Kansans until the 1920s.

The westward trails served as vital commercial and military highways until the railroad took over this role in the 1860s.

During this period, African Americans began migrating from the South in search of better opportunities. Promoters encouraged black families to move to Graham County in western Kansas. By the summer of 1877, prior to the African American “Exoduster” movement, 300 blacks established a new town called Nicodemus. Several African American settlements were established in other parts of the state.

Between the Civil War and 1890, Kansas experienced its most significant population increase in history. More than one million people streamed into Kansas, seeking a new life on the frontier. Many came to claim the free land offered to settlers by the Homestead Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1862.

Mexican workers came to Kansas during the construction of the railroads. They also found work in sugar beet production and later in manufacturing. Mexican immigrants settled in the southwest part of the state and in other areas where they found employment opportunities.

By the end of the 1800s, German-speaking people formed the largest group of new immigrants to Kansas. Many came from Germany, but many others lived near the Volga River in Russia. They called themselves Volga-German or German-Russian.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2025.

Also See:

Coming of the Settlers to Kansas

Territorial Kansas & the Struggle For Statehood

Sources:

Connelley, William E.; A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans, Lewis, Chicago, 1918.

Kansapedia

Konza Prairie Biological Station

Transforming the West

Visit Leavenworth